On the right-hand side of the road as you sweep down from the hills into the village of Kravica in eastern Bosnia lies an empty white warehouse, standing squat and unremarkable in front of a row of trees. Nothing marks the spot as significant, but here, at around 6pm on the evening of July 14, 1995, 1,370 Bosnian men were slaughtered, one of several separate atrocities that took place that week in what would become known around the world as the Srebrenica genocide.

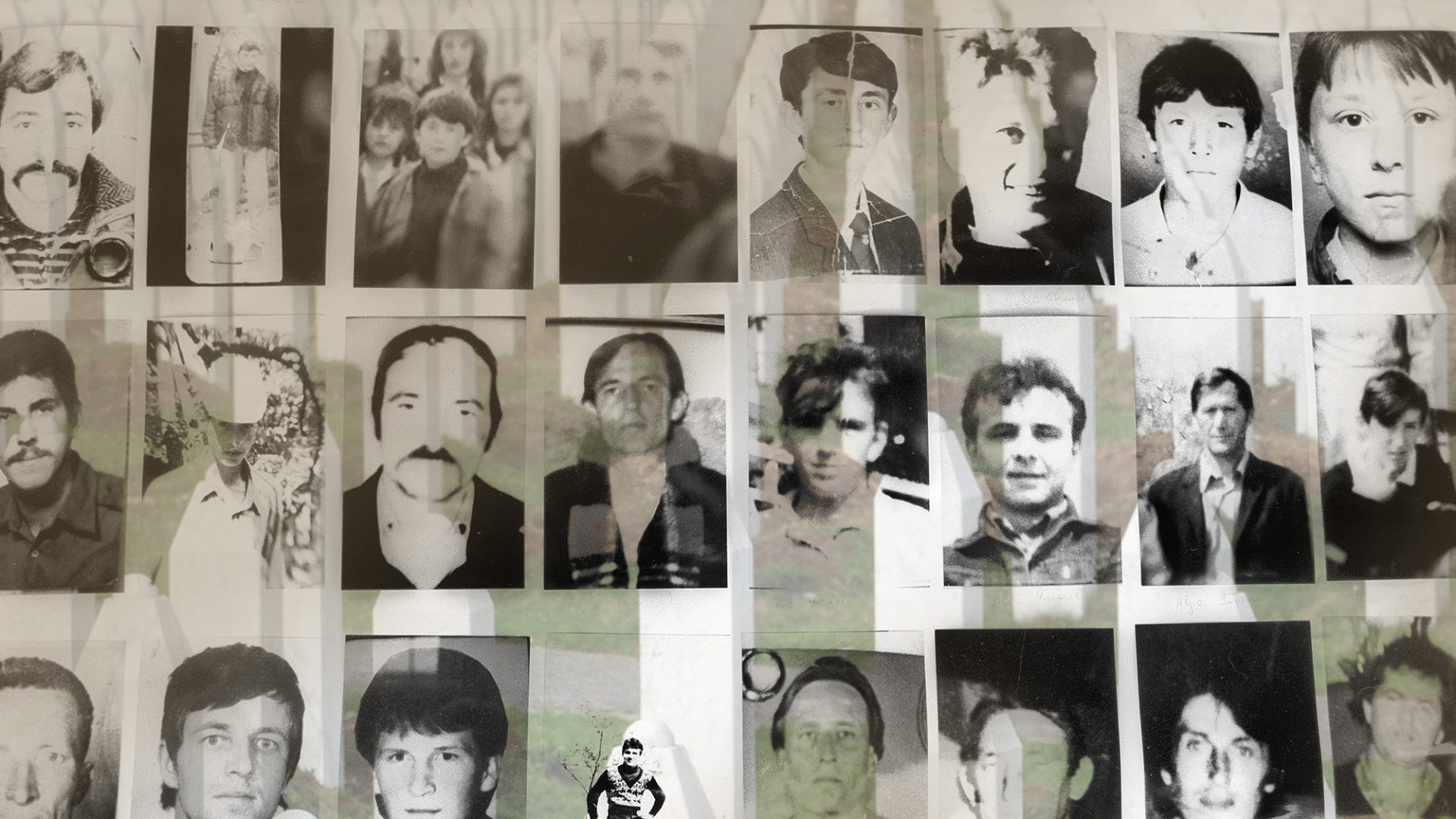

The men had been trying to flee advancing Serb troops who had overrun the nearby UN safe haven. Marched here, they had been packed into the warehouse. Then, according to witnesses, the soldiers threw in grenades, opened fire with sub-machine guns and cut down any who tried to flee. Blurred images from the time show bodies strewn around the front door. They were soon buried in mass graves nearby, before being exhumed and dispersed into smaller sites a few weeks later as Serb forces sought to hide the extent of what had happened.

More than 8,000 were killed or are still missing following the insane rampage of violence led by General Ratko Mladić who, upon arriving in Srebrenica that July, had vowed “revenge” upon the local “Turks” for the defeat inflicted by Muslims on Serb forces during the Ottoman empire in the early 19th century. Yet while 200-year-old history was used to justify murder and rape, today the not-yet 30-year-old mass execution of Bosniaks (the name given to the Muslim population in the region) in the early 90s is being denied. “There are people now who say the bones are from dogs, or Serbian soldiers killed in the 19th century,” one official told us last week.

I was among a small group brought to this beautiful Balkan country by the charity Beyond Srebrenica. When we drove past Kravica, in silken autumn sunshine, there was no evidence of what happened here three decades ago. The warehouse is within Republika Srpska, the Serb-dominated section of Bosnia, and the authorities have replastered its walls, removing evidence of the bullet holes. Meanwhile, a fence has been erected to prevent the mothers, wives and children of the victims from laying flowers. When the women visit now, they have to stand behind it.

Which is where the local Serbian leaders would like to place discussion of the genocide altogether: fenced off and placed at a distance. Milorad Dodik, the president of Republika Srpska, now argues that while the massacre was a “mistake” and a “crime”, “it wasn’t genocide”. He and the president of neighbouring Serbia, Aleksandar Vučić, claim that Serbia is becoming an international whipping boy over the genocide. This summer, a German-led UN resolution designated July 11 as the “International Day of Reflection and Commemoration of the 1995 Genocide”. “Its only purpose was to put moral guilt on one nation: on the people of Serbia and Republika Srpska,” Vučić responded. That’s despite the fact that nobody has ever accused ‘the people of Serbia’ of committing genocide; only the people who ordered and carried it out.

And the war of words over Srebrenica is only the tip of the iceberg. An “all-Serbian” statement in June, signed by Vučić and Dodik, proposes the dramatic weakening of the Bosnian state, reviving memories of times past. Dodik is openly campaigning for Republika Srpska to secede from Bosnia, in a move that would spark regional conflict. The Serbs are backed by neighbouring Russia, whose influence in the region is growing. And that was all before Donald Trump was elected to the White House, throwing western support for Bosnia into doubt. Incredibly, only 30 years on from the killings in Bosnia, the region is back in a dangerous place, ignored once again due to the hot conflicts elsewhere, but no less perilous for that. Aggressive nationalism, political corruption in Bosnia, the menace of organised crime, and the posturing of self-interested leaders who prefer to stoke mistrust of the other, heralds a quiet fear that it could happen again.

We are accustomed in the UK to treating politics as a nuisance and an irritant. Bosnia reminds you that it matters, and matters a lot. Politics is failing again here and when politics fails, tragedy invariably follows. That tragedy is all the worse in Bosnia because it is being visited upon people who are still suffering from the last time politics failed here, who are still fighting to ensure those lessons aren’t forgotten, and still believing in a lasting future for a multi-ethnic nation.

They number Mejra Dogaz, whom we met at Srebrenica’s cemetery, where the tombstones of the 6,671 bodies that have been found from the genocide now stretch up the hill and into the fields beyond. By the time Serb tanks rolled along the nearby road in 1995, Mejra had already lost her husband, Mustapha, and her eldest son, Zuhdija, to the war. That week her remaining boys, 19-year-old Omer and 21-year-old Munib, were murdered too. She fled, and returned in 2002. “I would never have returned to Srebrenica if one of my children was alive, but since they are all dead, then this is the only place I can be near to them,” she told us.

But when she got back, the torment continued. She saw men who had been guests at her sons’ weddings but who had taken part in the killings. “When I returned to the house, a man who was a schoolfriend of my children tried to run over me in his truck and kill me.” We were told that pigs’ heads are being left at the entrance to the memorial site. Now she speaks to visitors like us to use all she has left: her voice. “Why do we do this? We are fighting for justice and truth to be heard. Our fight is for the truth and justice for our beloved ones who were killed.”

In the centre itself we met a softly-spoken local engineer called Nedzad Avdić. As a teenage boy that July he was singled out for execution and shot four times during one of the mass executions nearby, but somehow managed to crawl away to safety, hiding in a nearby canal until the soldiers left. The only other survivor from that night has now gone to live in the USA. But, like Mejra, Nedzad told us he opted to return to pay witness to what happened. “I remember the words of my mother. She says go anywhere but please don’t go (back) to Srebrenica. But I can’t erase it from my mind. It’s a kind of therapy for me,” he told us.

A brutal question to ask these people 30 years on is: isn’t it time to stop? Aren’t we always encouraged to “move on” in life? After 30 years, many might argue that Bosnians, too, should confine the war to history and forget about it. Meeting these people makes you understand the fallacy of that argument.

A three-hour drive away in Sarajevo we meet Nihad Branković from the International Commission on Missing Persons, which is still going about the grisly business of finding body parts and remains from the war; in 2023, they found a further 89. Many more are still unaccounted for. Due to the fact that decaying bodies were dug up and mishandled, the body parts of one man, for example, were discovered in eight separate locations. Why continue with this torment? Nihad tells the story of a group of young people in Catalonia he had met who, 80 years on from the Spanish civil war, were still talking of their hurt over the failure to find the remains of grandparents and great-grandparents they had never even met. “If you let it go, you leave the wound unhealed and it will be worse in 50 or 60 years’ time,” he says.

Across town, the same question is answered emphatically by Bakira Hasečić, the tenacious and courageous founder of the Association of Women Victims of War. Raped by a soldier during the war, she set up this tiny organisation in Sarajevo, in her words “to collect the stories and collect the evidence about women who were raped in the war with the sole purpose of punishing the war criminals”. There is a message she’s sending. “We want to leave a legacy so these stories are a reminder for anyone who might think they can repeat this thing, that we will not stop until every war criminal is behind bars.”

That task – to deliver justice and closure on the past – remains vital, in short. But what of the future for this nation and the wider region? Bosnia formally applied for EU membership in 2016, but the process has stalled thanks to the failure to reform: the Office of the High Representative – a temporary measure to oversee the implementation of the Dayton peace agreement – is still open. And for self-serving party hierarchies who are earning plenty from state and military property ownership, there is little incentive to adopt the EU’s strictures. This is all having a damaging effect on the country; it denies people hope of progress. We were told by our guide that, with EU entry now feeling so distant, many Bosnians aren’t hanging around to wait and are finding a life elsewhere.

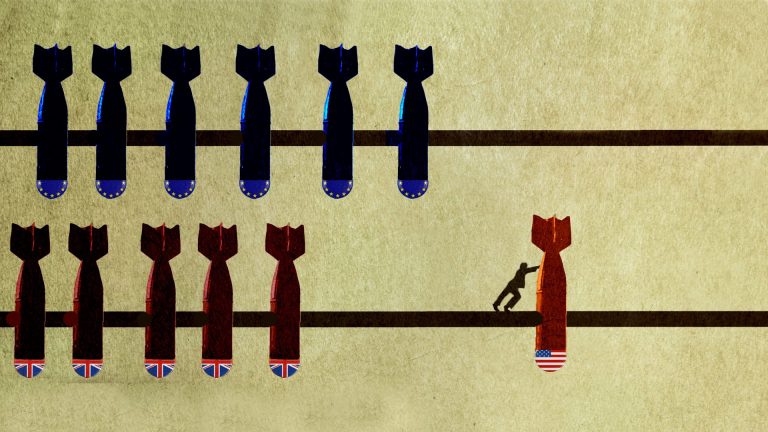

With the risk of radicalisation stalking the country, and aggressive nationalism steadily growing, it is now vital that Europe gets behind Bosnia and throws significant weight behind a credible path towards EU entry. The EU shouldn’t be surprised if its failure to do so is exploited by Russia, as Vladimir Putin strives to put the region within his own sphere of influence. With the US under Trump now an unreliable partner in the region, European leaders need to step up to show they are serious about accession. Bosnians have long learned to be sceptical of help from western partners, be they the EU or the UN. Here is an opportunity for Europe to make up for some of the cowardice and neglect of the past.

In the Bosnian capital of Sarajevo, there’s a street where east literally meets west. In one direction is the old town, where the smoke from restaurants selling delicious plates of local Cevapi hangs in the air. Turn 180 degrees, and you’re a few hundred metres from the Catholic cathedral with its mountainous statue of Pope John Paul II, in what could be any fair-sized city in western Europe. The contrast has been seized upon by local tourist chiefs as a nice way to symbolise the city’s position as a meeting point between the two continents.

But to suggest the battle in Bosnia is between east and west would be a total misreading. This isn’t a war between civilisations. It’s a contest between the flattened, diminished vision of a country divided down ethnic lines, and that of a nation that holds true to its multi-ethnic roots, where east and west mingle, shop, eat and love together. It’s a battle about civilisation.

Is it possible, in the age of rising nationalism, to nourish this richer, truer version of civilisation? Is it possible to foster a complex, layered society where ethnic differences are celebrated and cherished? Is it still possible to believe that politics can offer solutions? That’s the question Bosnia poses to all of us, and it’s the question the graves of Srebrenica insist we face. Will we? Never again, we said at Auschwitz and then at Srebrenica, too. Thirty years on, I fear we are once again letting them down.

The charity Beyond Srebenica Welcome – Beyond Srebenica seeks to educate and raise awareness about the genocide