Hungary 1956. Czechoslovakia 1968. These are the familiar benchmarks of the Soviet Union’s brutal oppression of its satellite states in eastern Europe. The tanks of the Red Army patrolling the streets of Budapest and Prague, protesters shot, dissidents rounded up.

Perhaps because there were no tanks rolling across international borders, perhaps because it was over in a matter of hours, the East German Uprising of June 1953 seems almost a footnote to these later rebellions. But it was arguably just as significant and just as brutal. And its consequences were devastating: it was one of many factors that led, eight years later, to the construction of that most notorious of political barriers, the Berlin Wall.

“Afterwards, they said nobody knew anything about it outside Berlin, that the government successfully suppressed the news and covered it up. But that’s not true,” says Michael Weber, who in June 1953 was an 18-year-old student living in Buckow, 15km to the east of Berlin, the capital of what was called the German Democratic Republic (GDR). “My cousin returned from working in Berlin on June 17 and she said something was happening. But we had already heard from people who could listen to radio stations in the west.”

Seventy years on from the 1953 uprising, Weber, now 88, is one of the few remaining eyewitnesses to its aftermath. He had already lived through a period of cataclysmic change: a schoolboy during the second world war who now saw his country and its capital divided.

The uprising offered an opportunity to participate in what, it was hoped, would be a far more positive piece of history. And so, he says, “a few of us decided to travel to Berlin. We thought the authorities would close the railways, so we took my cousin’s car. This was on the Friday, two days after the uprising began, so things were settling down.

“Police stopped us on the outskirts of Berlin and told us to turn back, they said there was a chemical spill ahead. The other two people in our car returned to Buckow by bus. But me and my cousin continued on side streets. We weren’t politically minded so much as curious.

“We parked up near Alexanderplatz,” continues Weber. “There were damaged buildings, burnt cars. Very few people were about, and twice the police asked what we were doing. In hindsight, I’m amazed we weren’t arrested.”

The road to the uprising began the previous year, when the general secretary of the GDR’s ruling Socialist Unity Party (SED), Walter Ulbricht, decreed the country would proceed with “accelerated construction of socialism”. The western powers had just rejected Soviet leader Joseph Stalin’s suggestion of a unified, unarmed Germany, fearing it was a propaganda stunt.

“There’s evidence to suggest the unification idea came from Ulbricht himself,” says Richard Millington, senior lecturer in German at the University of Chester and author of State, Society, and Memories of the Uprising of 17 June 1953 in the GDR. “He knew the western allies would almost certainly refuse and then he could blame them for the division of Germany, consolidating his own position.”

So Ulbricht pressed ahead with transforming East Germany into a satellite of the Soviet Union. Effectively he was “Sovietising” the economy, investing in heavy industry, creating state farming collectives and taxing remaining private enterprise.

“Ulbricht was following the Soviet mantra of ‘industrialisation leads to modernisation’,” says Millington. “The Sovietisation of the GDR was the final nail in the coffin of German unification.”

What Ulbricht hadn’t budgeted for was the Soviet Union’s demand that the GDR establish its own army, to relieve the USSR of the burden. This, coupled with industrial investment, gobbled up state funds. By 1953, the effects were showing. “There was a consequent lack of investment in consumer goods – cars, TVs, fridges and the rest, so life became more difficult,” explains Millington. “And workers were told to increase productivity by 10% just to get the same wage. Farmers were instructed to collectivise their farms and give up their land, while being set impossible-to-meet production figures.”

Food prices rose as farmers fled west across the still relatively porous border, leaving crops unharvested. Living standards plummeted and food queues increased. Power cuts were commonplace. The government slogan of “First work harder, then live better” infuriated rather than galvanised. In the first four months of 1953, 122,000 East Germans upped sticks and left.

In Moscow, the situation had changed dramatically. Stalin, the autocrat who had ruled for three decades, died suddenly on March 5. The new Soviet leadership realised Ulbricht’s process of “Sovietisation” was moving too quickly. He was summoned to Moscow and ordered to halt the process. Suddenly the SED appeared weak and in thrall to their Soviet masters, admitting to their compatriots that “mistakes had been made.” Crucially, they would not back down on the work quota increase.

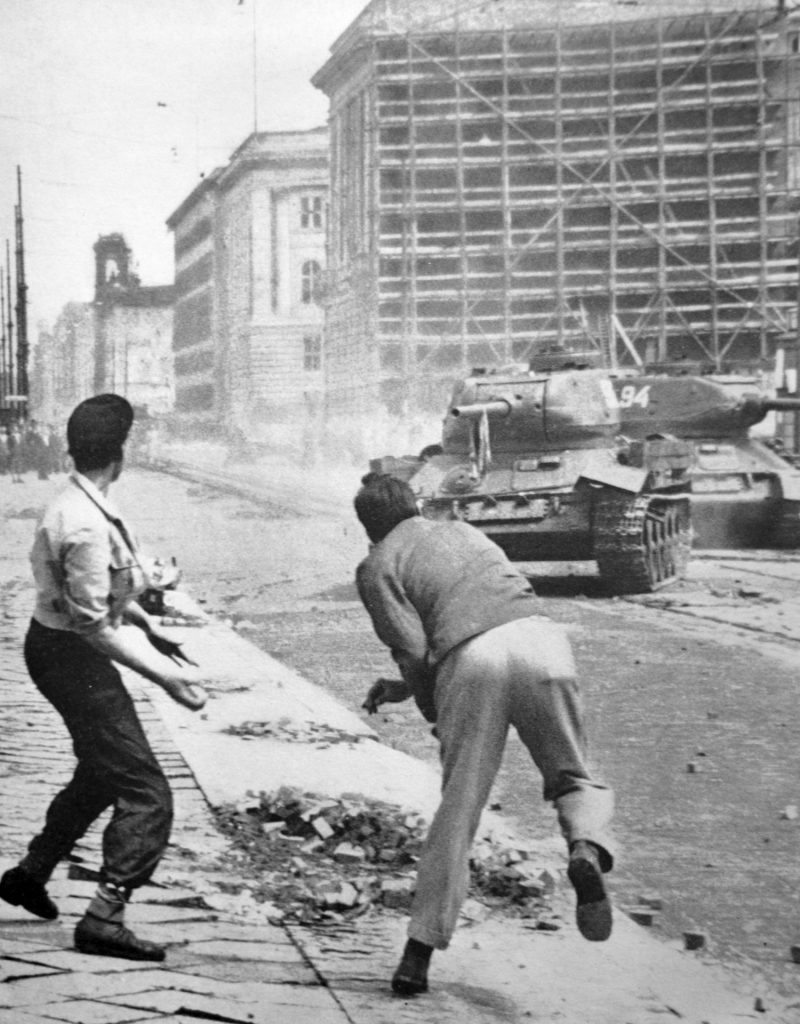

On June 16, construction workers marched down East Berlin’s Stalinallee to the headquarters of the East German Trade Union Federation, demanding that the increase in production quotas be revoked and calling for a general strike the following day. More protesters joined as they moved on to SED headquarters on Wilhelm-Pieck Strasse.

The politburo vacillated. Western radio outlets – particularly Radio in the American Sector (RIAS) – began broadcasting news of unrest. In the early hours of June 17 the Soviet high commissioner for East Germany, Vladimir Semyonov, told Ulbricht he would deploy Soviet troops on the streets of Berlin.

It was, to use the cliché, a perfect storm. The workers believed their demonstration had had the desired effect and began to demand the resignation of Ulbricht and the SED. Meanwhile, there was no way the Soviet Union was going to allow its foothold in Germany to be usurped. There was only one outcome.

“East German newspapers on the morning of June 17 only reported in limited fashion what happened the night before,” says Millington. “They blamed western agents and fascists, saying it was an American-backed insurrection by people who wanted to see a return of the Third Reich.” But it was too late, Millington adds: “Many East Germans could receive RIAS and news spread by word of mouth. All over the country, solidarity was declared with the East Berlin workers. The official SED line in the newspapers was widely discredited.”

Former printer Volker Doll, now 91, says: “I remember that morning well.” Doll worked near the central square of Alexanderplatz. “We heard a mass demonstration was planned at Strausberger Platz. We saw Russian troops on the streets and the special police of the Kasernierte Volkspolizei. Some asked us to return home, but at that point they weren’t threatening and anyway, we felt empowered, unstoppable. We had banners and chants and demands. People were burning SED posters and political statues were sprayed with paint.”

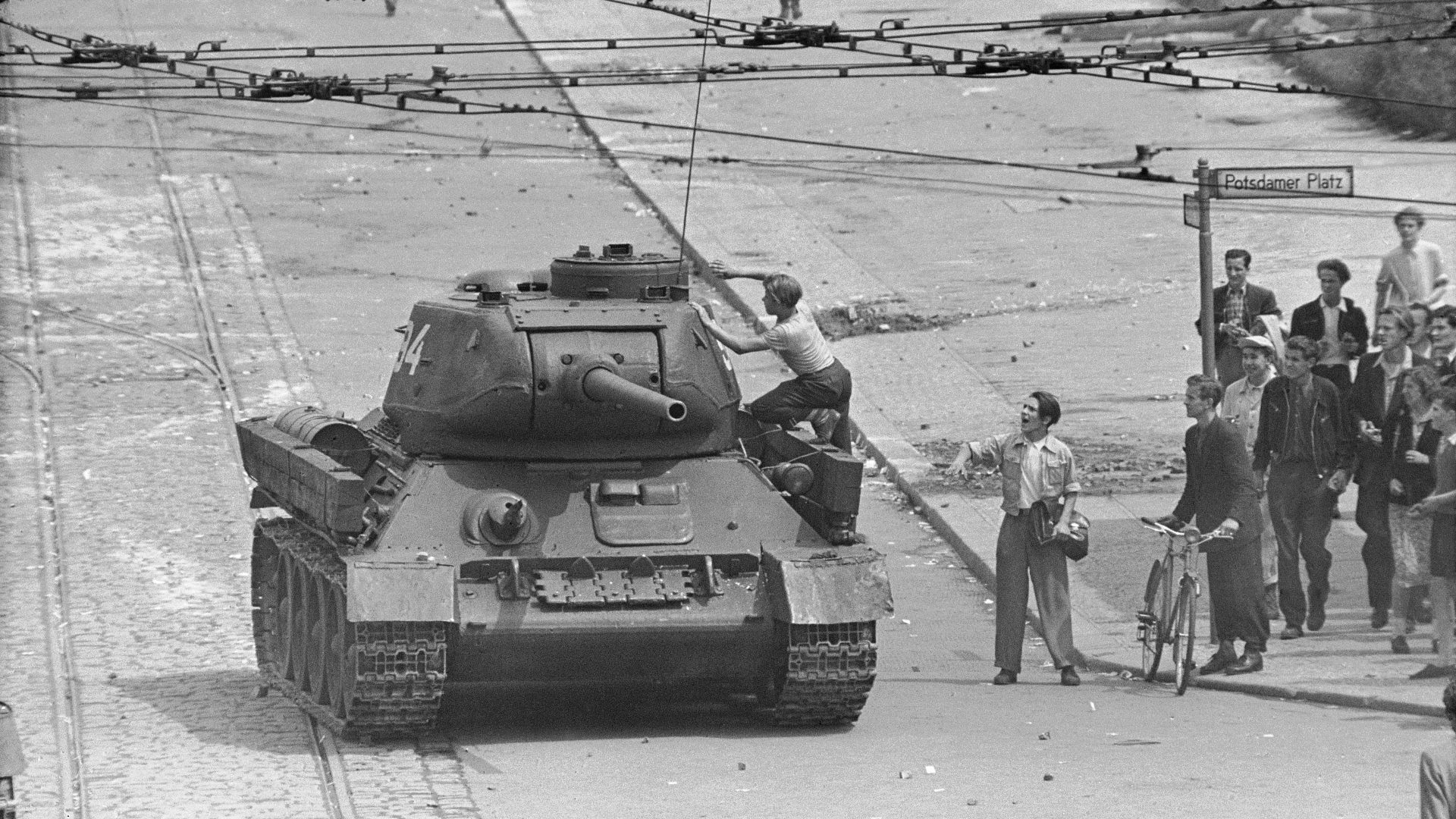

“But then the tanks appeared,” says Doll. “And they were Russian. It was frightening and confusing. I returned to Alexanderplatz, but the authorities were cutting off streets and terminating trams. I went home and waited, expecting a knock on my door.”

Doll was lucky. The police never came. But the border to the west was sealed. And as the demonstrators approached the central police station throwing bricks and bottles, the tanks began firing, and 20,000 Soviet troops and the Volkspolizei took to the streets. The SED government decamped to the suburbs, and Semyonov declared martial law. Casualties are officially listed as 39 dead, including five members of the security forces, although some estimates say the figure is 10 times that, with hundreds wounded.

In the days afterwards the Stasi – the GDR’s repressive secret police – rounded up ringleaders. Possibly more than 10,000 were arrested and, over the course of the year, as many as 40 protesters, alongside Soviet troops who refused to obey orders, were tried and executed. Their number included West Berliner Willi Göttling.

When news reached West Berlin that workers in the East were confronting the authorities, many students and other activists crossed the border. Göttling, a painter and decorator, was one. He was apprehended, convicted of being an agent provocateur by a Russian military court, and executed. Like Peter Fechter, shot trying to climb the Berlin Wall in 1962, Göttling’s death stunned West Germany, made international news and brought home the brutality and implacability of the Soviet regime.

In cities all over the GDR, protesters had taken to the streets. “Figures vary,” says Millington, “but the number definitely topped 500,000. Others say it was a million. But some ordinary East Germans were critical of the violence. The uprising was as much an orgy of destruction as it was a political act, with no coordination of the protests. In many places things were destroyed for little reason, a mass outpouring of fury with no true aim. And there was shooting from both sides. One police informer was attacked, rescued by ambulance, then dragged out and drowned.”

In the short term, the crushing of the uprising showed East Germans what would happen if they protested again. “But also it showed the SED was bankrupt, only in power because Soviet troops were there,” says Millington. Party membership collapsed but, against the odds, Ulbricht survived.

The United States had begun distributing food parcels to East Germans prepared to travel to West Berlin to collect them. It was a deliberate attempt to undermine the SED. It seemed only a matter of time before Ulbricht would be toppled, but internal distractions in Moscow following Stalin’s death in effect led the Soviets to opt for the status quo, forcing new economic and political policies on Ulbricht, but allowing him to stay in power. Ulbricht’s position was secure as long as he did Moscow’s bidding. He subsidised the cost of living and increased the reach of the Stasi which, according to some estimates, would eventually have one informer for every 166 people, far more than the Gestapo or the KGB.

“Even as the uprising faded from popular memory, the party never forgot,” says Millington. “They frequently referred to ‘the spectre of ’53’.”

And in 1961, construction of the Berlin Wall began – the most potent symbol of what Winston Churchill described as the Iron Curtain – to ensure the drain of workers to the west would cease.

Despite its significance, the uprising does not have the same resonance in the cold war narrative as other suppressions of dissent such as the aforementioned Czechoslovakia or Hungary. Possibly one reason is that Russian troops were already stationed in the GDR. There were no chilling images of tanks rolling across borders. Millington, however, suspects other factors play a bigger role. “It only lasted one day,” he points out. “Had it gone on longer, Soviet troops may have been sent by Moscow. Also there was no charismatic opposition leader. In Czechoslovakia in 1968 you had Alexander Dubček, and in Hungary in 1956 there was Imre Nagy. Ulbricht had no obvious challenger.”

In West Germany, June 17 became a national holiday. “The West German establishment seized on 1953 as a positive act, the first by Germans since the second world war, showing that Germans could oppose dictators, and favoured freedom and democracy,” says Millington. “It was uttered in the same breath as the plot to kill Hitler.”

Angela Merkel, the former chancellor of a reunited Germany who was brought up in East Germany, often states that the uprising was the forerunner of 1989, the year the Berlin Wall fell. Millington, however, says it’s difficult to draw a direct line between 1953 and 1989.

“East Germany lasted another 36 years,” he points out. “What the demonstrators in 1953 demanded was different to those of 1989, who initially wanted to refine socialism, not usurp it. How many people were thinking about 1953 in 1989? Maybe older ones, but not younger ones.”

One older woman definitely was. Silke Behrendt was a telephonist in West Berlin in 1953. She is now 89, but recalls communications suddenly being cut off. “I had made friends with a woman in a telephone exchange in the east of the city,” she recalls. “We knew something was happening and I was scared. I thought that because she had befriended me she was in serious trouble. I wept when she called the following week. So many people here have forgotten about 1953, young people never even learn about it. But to me, it was the time when Germany was finally set on the road to reunification.”