When was Dominic Cummings born? Literally speaking, the answer is November 25, 1971. But I’m not speaking literally. What I mean is, when did the Cummings whom we all know today – the brain of Brexit, the weirdo on Whitehall, the Substack scourge – really come into being?

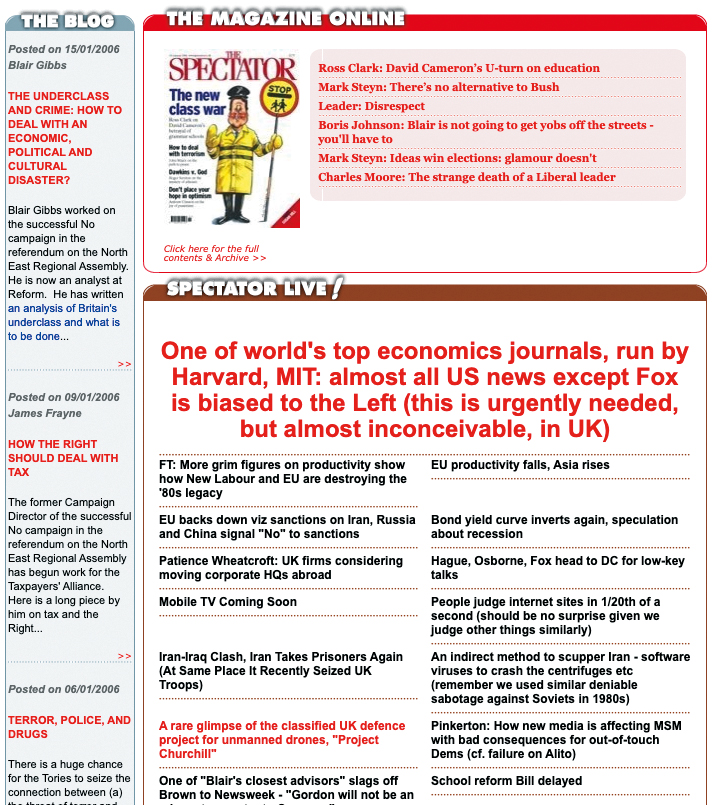

By my calculations, it was sometime around the beginning of 2006. That was when Cummings was online editor of The Spectator and had the opportunity not just to shape but also to be the digital voice of a magazine that was wrangling for the first time with the internet after almost 180 years of printed comfort. What he did is still partially visible on internet archive sites.

There, on The Spectator homepage, was a box called Spectator Live! and that exclamation mark was far from the kookiest thing about it. This was a sort of bulletin board, clearly inspired by the longstanding US website The Drudge Report, that linked to articles and other bloggery from across the web. There was no byline on this section, no way of knowing then who was both choosing and adding commentary to the links; but it’s all too clear now.

Scientific links abounded: one was to an article by Paul D. Spudis, the late geologist and lunar expert, on how returning to the moon would “Help Science, The Spirit, And Slow Global Warming”.

There were plenty of spiky asides about the then-young Tory leadership of David Cameron: “…no signs of serious intellectual effort”. And stories categorised under headings such as “Comedy Britain” and “Comedy Diplomacy”.

But one story exercised the Spectator’s online curator, Cummings, more than any other: the publication of 12 cartoon depictions of the Islamic prophet Muhammed in the Danish newspaper Jyllands-Posten. Or, rather, it was what he regarded as the lily-livered response of European leaders and journalists that really got him going.

First, he linked to every editorial on the subject he could find. Then came angrier and angrier commentary, including an all-caps quote from Friedrich Nietzsche’s Beyond Good and Evil: “THERE IS NOTHING SO TIMELY AS WEAKNESS OF WILL.” Eventually, he’d go even further by simply publishing one of the cartoons on The Spectator homepage – an act that potentially risked the safety of his colleagues in the magazine’s Bloomsbury offices, where Cummings, well, wasn’t. At the time, he mostly worked from his family farm near Durham.

The cartoon was soon taken down. And Cummings left The Spectator just weeks later, a particularly brief stint in a career marked by early departures. He’d done a fair amount before then, of course; particularly for someone who was still comfortably in his thirties. There was a contentious spell as director of strategy for Iain Duncan Smith’s Conservative Party, followed by a successful campaign to resist a regional assembly in the North East, among other achievements.

But none of it heralded the coming of Cummings with as much clarity as that brief online editorship. The nerdy preoccupations; the distaste for everyday politics and politicians; the bloody-minded, even dangerous, conviction… all of it communicated through a form of proto-Twitter. He was the shock of the new, emanating from a body, The Spectator, that, in many respects, represented the spirit and sanctity of the old.

As I understand it, Cummings only slenderly overlapped with Boris Johnson at The Spectator. He had been tasked by Andrew Neil, the magazine’s chairman then and now, to put some pep into the digital operation just as Johnson’s notorious editorship was coming to its end in December 2005. He did precisely that – and then some – mostly under the acting editorship of Stuart Reid.

It would be years later, during the Brexit referendum campaign, until Cummings and Johnson would properly come together as a political force. And a few years later still, after Cummings departed Johnson’s No.10 in November 2020, that they would break up with megaton force. Yet both men still brought something of their Spectator selves into government. In fact, you might wonder whether Johnson ever really left the print editorship behind him. His meetings in No.10 sound much like the editorial meetings he once held in The Spectator’s old offices on London’s Doughty Street: freewheeling, inconclusive, and with more than one eye on who’s saying what about whom in the papers. He creates chaos, sometimes unwittingly, and tries to somersault out of it with a glass of champagne in his hand.

Whereas Cummings in No.10, as at The Spectator, was single-minded, plugged-in, sharp. There were some around him – including, it should be said, a number of civil servants – who found this bracing, especially in comparison to Johnson. But there were others who fell afoul of his zeal. The departure of Sajid Javid’s adviser Sonia Khan, escorted away from Downing Street by the police after allegations of leaking, was a big moment in the divide over Dom. His allies claim that he never meant for that kind of fallout. His detractors are more succinct: “Disgusting.”

In theory, this mix – of two men who, despite their similar ages (Johnson is 57, Cummings is 50), are generations apart in methods and worldview – might have worked well. The old and the new, the rake and the rapier, both compensating for each other’s deficiencies. For his part, Cummings has made it clear he hoped to hitch his agenda on to a prime minister who doesn’t really have one of his own.

However, in the end, the two proved incompatible. It was the shock of the new, all over again. And it has left us with the extraordinary fact that the fiercest battle in British politics today – over lies, parties and Covid – is taking place between one of The Spectator’s former editors and one of its former online editors.

At which point, I should probably admit my own, very incidental, status: I was online editor of The Spectator between 2008 and 2012, making me, technically, one of Cummings’ successors. By that time, thanks to the ingenuity of several editors and writers, the magazine had already found its place online – a mix of elegance and energy, exemplified by the Coffee House blog. Everything fitted together with fewer abrasions than had been the case during the mash-up experiments of the Spectator Live! era.

But, even though he’d left years before and was then working for Michael Gove, Cummings was still unavoidable at The Spectator. He was, let’s say, involved in some of the magazine’s political journalism. More significantly, he was a literal part of the family. He and Mary Wakefield, then the deputy editor and currently both commissioning editor and a columnist, were married in 2011 and now have a son together.

It was through Wakefield that I was first introduced to Cummings – twice. Once was outside Westminster’s Two Chairmen pub; a brief nod in the direction of the new kid, me. The other time was at a separate Spectator wedding in 2011, between James Forsyth, the magazine’s political editor, and Allegra Stratton, then working at The Guardian. A few of us were waiting to be ferried to the venue, when Mary did the whole “Pete, Dom; Dom, Pete” routine.

What struck me was the quietness of Cummings. He mumbled his hellos, and that was that. Perhaps if he’d found me interesting, he might have been more voluble – but I’ve never had much to say about Russian literature, machine learning, nor superforecasting.

Still, with what I knew of him, this quietness surprised me at the time. It doesn’t any more. As someone who worked with Cummings in the coalition government put it to me: “There are just two different people in the same body.” One Dominic, on this account, is the “intellectual, thoughtful rationalist”. The other is “the political campaigner”. And the differences between the two are almost physical: “He gets very energetic, wound-up, almost hyper, when he’s in campaigning mode.” I was clearly encountering the rationalist.

That same wedding has since been written into modern political folklore – and further tangled the ties between The Spectator and the current government. Stratton, of course, became Johnson’s press secretary in 2020, before recently taking the fall for joking about parties that the prime minister variably either knew about or attended. Matt Hancock was ushering people towards their seats in the church, years before he ushered colleagues into his sweaty-palmed grip.

But the standout participant, at least from the vantage point of 2022, was Rishi Sunak. He was Forsyth’s best man, the two having become close friends at school, and he delivered a speech that was full of wit and warmth. Sunak was some distance from entering politics at this point – he was a pretty diminutive-seeming financier – so for most people in the very political audience this would have been a first encounter.

And perhaps it was for Cummings, too. Or perhaps he’d met Sunak before then, during one of the meetups between the Cummings-Wakefield and Forsyth-Stratton households in North London.

Whatever the case, there is now what might be called a fellowship between Cummings and Sunak. In his early years as MP for Richmond (Yorkshire), Sunak published a think-tank pamphlet called The Free Ports Opportunity, arguing that “Brexit will provide the UK with new economic freedom”, including the freedom to set up special areas of financial and technological experimentation intended to stimulate local growth. This was both a Cummings-esque policy – one that’s now being implemented by the Treasury – and a statement: Sunak is a true believer in Brexit. But true belief, by itself, isn’t sufficient for Cummings. The main reason why he encouraged Sunak’s rise to the Chancellorship in 2020, at the expense of Javid and his team, was contained in his testimony to last year’s parliamentary inquiry into the lessons of the pandemic.

“I knew that Rishi and his team… were extremely competent,” he said to the questioning MP, Rebecca Long-Bailey.

Extremely competent! The words stood out amid all the criticism aimed at Johnson (“1,000 times far too obsessed with the media”) and Hancock (“criminal”) during the testimony, but especially in the context of Cummings’ entire career spent lamenting the quality of the elected class. In Sunak he sees something of a new model politician: someone who learnt about tech, data and organisation in the clinical world of transatlantic hedge funds, and who has now brought that knowledge to bear in Westminster.

There is no doubt that Cummings would like Sunak to move from No.11 to No.10. What is in doubt is how much he can do to effect that change from outside government, although he is certainly trying his hardest.

The ongoing campaign against Johnson is, according to several friends of Cummings I have spoken to, unlikely to be motivated purely by revenge but mainly by a desire to see his ideal politics implemented more effectively. It is also, it should be noted, unprecedented. Before now, the epitome of political bloodletting was Geoffrey Howe’s polite Commons speech announcing his retirement from Margaret Thatcher’s government. Cummings’ stream of emails, photos and invective is literally from a different age, a 21st-century beast.

And there is, it seems, more to come. Indeed, in an update to his most recent newsletter, Cummings promises: “I’ll say more when [Sue Gray’s] report is published.”

Beyond that? Even if there is currently contact between the chancellor and the former No.10 adviser, it is happening without fingerprints – and that would have to remain the case were Johnson successfully brought down and Sunak brought to power. Cummings is far too contentious a figure for a return to frontline politics in the short or medium term, even if he has made improbable returns in the past. The centre is now closed to him.

Which leaves, of course, the fringes. Since leaving government, Cummings has filed the papers for a solo tech-consultancy firm. It’s named Siwah, presumably after the location in Libya where, according to some ancient sources, Alexander the Great had his divine lineage confirmed by the Oracle of Ammon.

There is also, of course, the Substack newsletter that supplanted his blog last year. This is the primary venue for Cummings’ public thinking about everything from the paroxysms of the Johnson administration to the lessons of Lee Kuan Yew’s leadership in Singapore – and it must be quite a money-spinner. Although Substack doesn’t give out numbers for individual newsletters, Cummings himself advertises “thousands of paid subscribers”, each shelling out at least £8 a month. I have heard informed speculation that he will make “hundreds of thousands” a year from this particular venture.

And so, in a strange way, he is back to the old Spectator Live! days, venting his spleen and exploring his interests on the internet. But, if I can invert the old French saying, the more things stay the same, the more they change. The Cummings who is writing now is different from the one who was writing back in 2006, if only in stature. And the fringes he occupies are pretty big, too. His newsletter has an enthusiastic following among Silicon Valley’s move-fast-and-break-things set. Tech billionaires have his number.

Could that be the next move for Cummings? To wreak massive change from outside the parameters of normal politics? When I ask one of his friends, the answer amounts to a shrug: “I don’t have a clue.” Another says: “There’s definitely not a masterplan for the next five years.” They are all adamant that he doesn’t care about money.

But it’s worth noting the words of Cummings himself, in his interview with the BBC’s Laura Kuenssberg last August. “What are the different possibilities to create different kinds of networked power in the world,” he wondered out loud, “that can do things without necessarily having to directly go and control the existing parties now or the civil service?”

Then there’s that CV. This is a man who has left a great, dripping mark on British political history, and who may well destroy the prime minister he helped to create. It’s a record that doesn’t go down well in Westminster, but among the New Alexanders of America – those who, like Elon Musk, aim to die on Mars – it might be towering enough to provoke a second glance. The spectator is definitely now the spectated.