On November 25, the first anniversary of Diego Maradona’s death will be marked with solemnity by the clubs that loved him. The chaotic manner of his departure – a heart attack after hours of feeling unwell at home, when he really should have been in hospital following recent surgery to remove a blood clot on his brain – will be forgotten.

So will the years of turmoil and indulgence that led him there.

It will be a day in which all that really matters is the genius of probably the greatest footballer ever to play the game.

The mourning will bring a stillness to noisy Napoli, where Maradona is still revered as a God and where he had the defining era of his career, one in which he almost single-handedly brought long-awaited success to a team that had gone more than 60 years without a Sscudetto. Tribute will be paid at the Stadio San Paolo, now renamed the Stadio Diego Armando Maradona in his honour.

Boca Juniors, where he had an executive box until his death, will pause to remember him, as they plan a memorial friendly against Barcelona, where his short and relatively unsuccessful spell is still recalled with fondness, although tarnished by the notorious knee he delivered to the face of Miguel Angel Sola after a tempestuous Copa Del Ray cup final against Athletic Bilbao.

There will be respect from Argentinos Juniors, where it all began, and even among supporters of Newell’s Old Boys, where he spent a very brief spell at the start of his time back in Argentina before a final fling with Boca. But how, one wonders, will be the anniversary be greeted in Seville, where Maradona’s time would begin with goals and hope but would end with a club official calling him not fit enough even to play table tennis? In his autobiography, the Argentinian would call his accuser a “wanker”, while reflecting on his time at Sevilla, “I started to realise that my initial impression – that I was too big for them – was indeed the case.”

In 1991, Maradona had been served with a 15-month ban from football, having tested positive for cocaine. When his ban ended, he was still contracted to Napoli, but had made it clear that he had no desire to return to the club where he had experienced such success or the city where his addictions spun out of control, or to a newly installed young coach called Claudio Ranieri.

His difficulties were well-documented but, still aged just 31, he unsurprisingly attracted interest from some of the world’s biggest teams, not least Marseille and Real Madrid. His decision was to return to Spain, but not to the Bernabeu.

Maradona’s international coach for the 1986 World Cup, his most successful tournament on the world stage, had been Carlos Bilardo.

In 1992, Bilardo took over as head coach of Sevilla, who had just finished in the bottom half of the Spanish top flight.

Knowing the team needed inspiration, he made it clear to club president Luis Cuervas Vilches that he wanted to sign Maradona at all costs. Vilches didn’t need much persuading to bring the world’s most-gifted player to Andalucía, and made an initial approach to Napoli, with a package that was to be bankrolled in part by Silvio Berlusconi, via his company Mediaset.

The offer, though, was rejected outright by Napoli. If the involvement of one balding footballing megalomaniac in Berlusconi wasn’t enough, Napoli’s refusal to do business prompted the intervention of another; as Sepp Blatter, determined to see the most famous player on the planet playing again as the 1994 World Cup approached, invited both parties to FIFA headquarters in Switzerland to thrash out a deal.

As protracted negotiations were under way, Maradona, for his part, had been hit hard by the ban. Moving back to Buenos Aires, he had only been able to play in unofficial exhibition matches and, without football to build his life around, he had continued to struggle with his addictions. Having eventually detoxed and attempted to gain control of his weight, the prospect of reuniting with the coach who had led him to World Cup glory, ahead of the tournament in the USA, was one he was keen on. The thought of living in a beautiful region must also have had its attraction, as must the romantic idea of arriving at a club starved of success, and transforming them into champions, again almost single-handedly just as he had done in Naples.

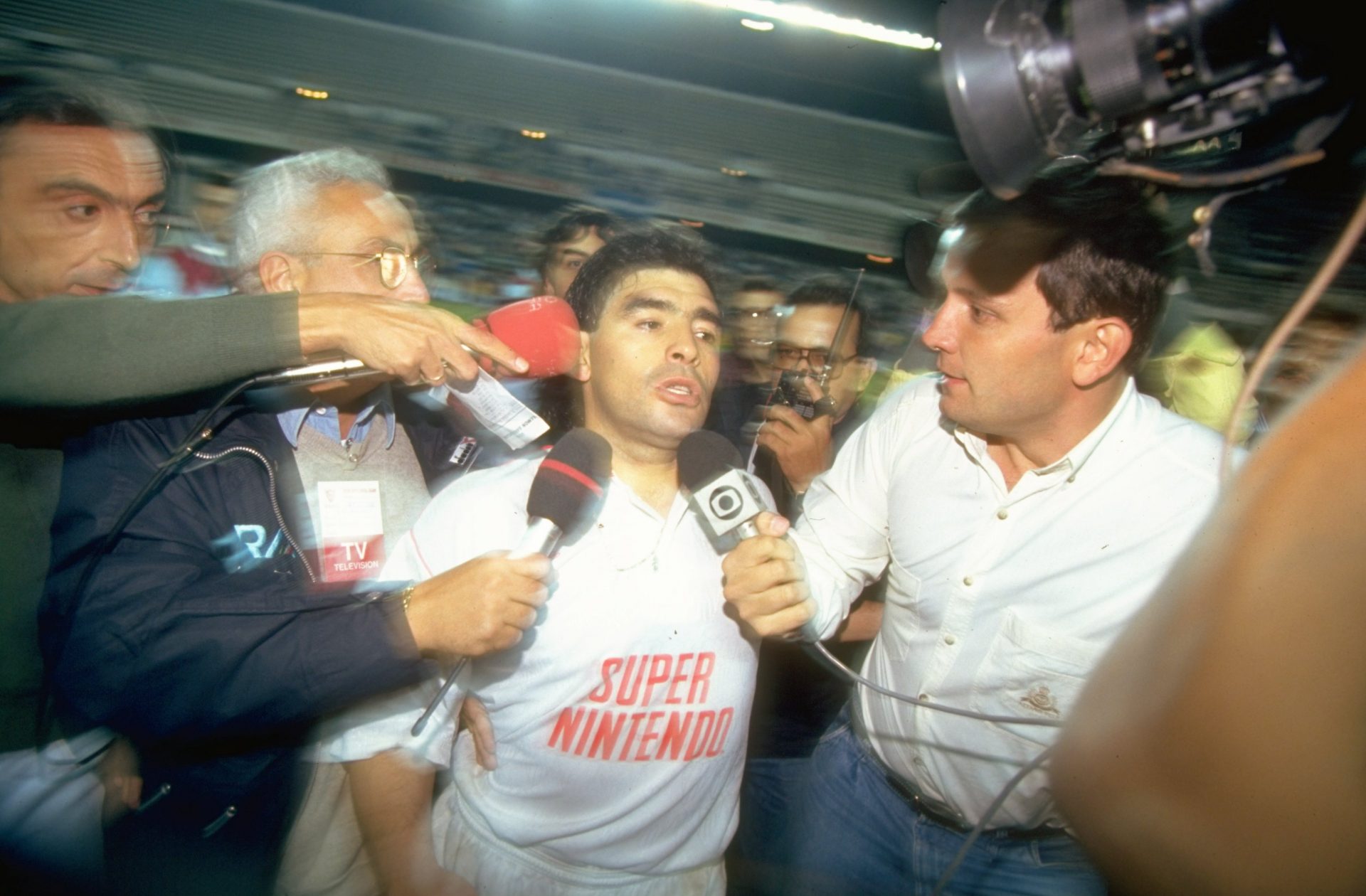

With the deal finalised, Maradona finally arrived in Spain in September 1992. Such was the protracted nature of contract negotiations, the La Liga season was already underway.

Just as Bilardo, Vilches and Blatter had all gone out of their way to secure his contract, upon his arrival, his new teammates went out of their way to make their new star man feel at home. Captain Manolo Jiménez gave him the captain’s armband. “We just couldn’t imagine him without it,” said Juan Martagón.

Bilardo made it very clear to his squad that the team would be built and structured entirely around the Argentinian legend. Training sessions were moved from morning to afternoon to fit in with the fondness for nightlife that was still very much in evidence. He was of course given the number 10 shirt with which he was synonymous. Far from resenting the preferential treatment being given to the new boy, squad members were more than happy to accommodate him.

“When I was a kid, I used to watch Diego on television in my room,” said Croatian striker Davor Suker. “Suddenly I found myself sharing breakfast, training and a lockerroom with him.”

Fellow Argentinian Diego Simeone was similarly effusive. “It was joy and happiness. It made us grow and I am grateful for the times that I have lived football with Maradona.”

The generosity extended to him by his new teammates was more than reciprocated by a man whose benevolence was just one more legendary facet of his personality.

Players, directors and staff received gifts of Rolex watches, designer clothes, free use of his collection of sports cars and lavish dinners and parties.

Understandably, the fans of a club who had long been stagnating in mid-table were also delirious with excitement at the prospect of Diego’s arrival, and season tickets sales jumped from 25,000 to more than 40,000.

When he finally took to the pitch, Maradona was keen to repay the faith the club and his former international coach had showed in him, and to play his way back into the Argentina squad in time for USA ‘94. As part of the deal for Mediaset to part-finance his contract, Maradona and his new team were obliged to participate in a series of high-profile friendlies, the first of which came against Bayern Munich, which Sevilla won 3-1.

Exhibition games against Galatasary, Porto, Lazio and Diego’s beloved Boca Juniors followed, but Maradona’s official Sevilla debut came at home to Real Zaragoza.

He may have been carrying an extra stone or two, but even a half-strength Maradona was likely to be the best player on the pitch, and so it proved, his touch and vision inspiring his teammates.

There were plenty of flashes of brilliance, including a superb free kick that curled around the wall and cannoned off the post.

Fittingly, he scored the winning goal, from the penalty spot.

While his presence didn’t quite inspire a Napoliesque surge, and the team’s main goal threat continued to come via Suker, Maradona undoubtedly played a pivotal part in a good run of form that put them in contention for a European place.

Pivotally, his form saw him recalled to the Argentina squad by coach Alfio Basile, who had ignored calls to recall the talisman, but now found himself unable to ignore a rejuvenated Maradona.

The player’s joy at being back in the international fold wasn’t shared by his club, however. Sevilla understandably viewed a series of meaningless international friendlies as less important than their push for Europe, and they refused him permission to travel until they had played their upcoming La Liga fixture away to Logroñés. Unsurprisingly, he left anyway, and Sevilla lost the game 2-0.

Almost overnight, the relationship between player and club irrevocably broke down. The former began to miss training sessions and allowed his weight to get further out of control, and the latter was rumoured to have hired a private detective in an attempt to deny him any payoff he may be due in the event of them deciding to cut ties.

Despite their previous international success, and the faith Bilardo had shown in helping Maradona revive his career, the relationship between player and coach also fell apart.

During a 1-1 draw at home to Burgos, Maradona was withdrawn early in the second half, and unleashed a torrent of abuse in Bilardo’s direction. The row continued in the dressing room, where the player would later claim he and his coach “kicked the shit out of each other.” It would be Maradona’s last action in Spain, as he missed the final game of the season, away to Sporting Gijón. A 3-1 win would prove too little, too late as Sevilla finished outside the UEFA Cup places on goal difference.

Just days later, Maradona left Spain, a mere eight months after his arrival. A lack of trophies and just five goals in 26 appearances may seem like an underwhelming episode in a glorious career, and it is one which was rapidly forgotten in the context of his earlier success and subsequent tumult, both at USA ‘94 where he followed a magnificent goal against Greece with one of the most famous goal celebrations of all time, only to receive another ban after testing positive for the banned substance ephedrine, and in his personal life.

His spell in Andalucía, though, is one that deserves recognition as a significant chapter in the career of the greatest player who ever lived.

FAMOUS FACES IN UNEXPECTED PLACES

Alessandro Del Piero, Sydney F.C. 2012

Del Piero was inarguably one of the greatest players of his generation, and one of Italy’s all-time greats. When his glittering time at Juventus came to an end, he ignored overtures from Liverpool, opting instead to spend two seasons in Australia’s A-League with Sydney F.C. and a short spell in India with Delhi Dynamos.

Pep Guardiola, Dorados de Sinaloa 2006

Following a money-making spell in Qatar after leaving Brescia, Pep was recruited by Juan Manuel Lillo, the man who would go on to be his assistant at Manchester City, to play for Dorados in Mexico. His spell there lasted a mere 10 games thanks to injury, and he embarked upon a managerial career that it’s fair to say has been fairly successful.

Henrik Larsson, Raa, 2012.

A legend at Celtic and across two spells with Helsinborgs, Larsson also left lasting impressions at Barcelona and Manchester United. After retiring in 2010, he laced up his boots once more for a short spell with Raa, down in the fifth tier of Swedish football. After a single appearance for them, he moved up a division, signing for Hogaborgs, where he played twice.

Joe Cole, Tampa Bay Rowdies, 2016.

Having at one time been seen as England’s next big thing and having won multiple trophies at Chelsea, Cole’s career wound up in the second tier of American soccer when he moved to Tampa Bay Rowdies. Cole played 82 games, before taking up an assistant manager’s role.

Nicolas Anelka, Mumbai City, 2014.

Anelka’s itinerant career took him to many of Europe’s biggest clubs, as well as a spell in China. After leaving West Brom in 2014, the final stop on his journey was at Mumbai City in the inaugural season of the Indian Super League. Anelka played 13 games across two seasons in Mumbai, scoring two goals.

David James, IBV, 2013

Despite the nickname “Calamity James”, the England goalkeeper had a hugely successful career with the likes of Liverpool, West Ham, Manchester City and Portsmouth, as well as playing 53 times for his country. Having eventually dropped down to League One, James spent a season as player-coach in the Icelandic top division with IBV, where he appeared 23 times.