The headline on the report in the Guardian was nothing if not arresting: “Revealed: secret cross-party summit held to confront failings of Brexit”. The newspaper reported in breathless terms that a group of politicians, business chiefs, former Whitehall officials (and a couple of journalists, myself included) had been gathered together by the Ditchley Foundation in Oxfordshire for a pow-wow on Brexit.

The discussion took place at Ditchley Park, a Grade I-listed Palladian stately pile that once appeared in an episode of Downton Abbey, and is like a step back in time. The house served as a country retreat for Churchill in the early years of the second world war when it was feared that Chequers was too obvious a target for German bombers. Today, it is home to the Ditchley Foundation, an organisation that hosts residential conferences which collect people from all corners of public life and, for a couple of days, sequesters them away to discuss the priority issues of the day.

On the Ditchley agenda that first week in February 2023 was a private discussion about how Brexit might be made to work better. The meeting was private, but not secret. Given all the toxicity that pervaded the Brexit debate nearly seven years after the 2016 referendum, the intention was to create a bipartisan safe space in which the challenges raised by life outside the EU could be dissected and discussed, with a view to working out what could be improved, within the bounds of political reality.

It was very deliberately a cross-party gathering, convened by one Labour and one Tory peer – Peter Mandelson and Jonathan Hill – both of whom had served as British cabinet ministers and as the UK’s commissioner to the European Commission in Brussels. Mandelson held the EU trade portfolio from 2004 to 2008, while Hill was EU financial services commissioner from November 2014 until June 2016 – when he followed David Cameron’s lead and resigned in the light of the UK’s vote to leave.

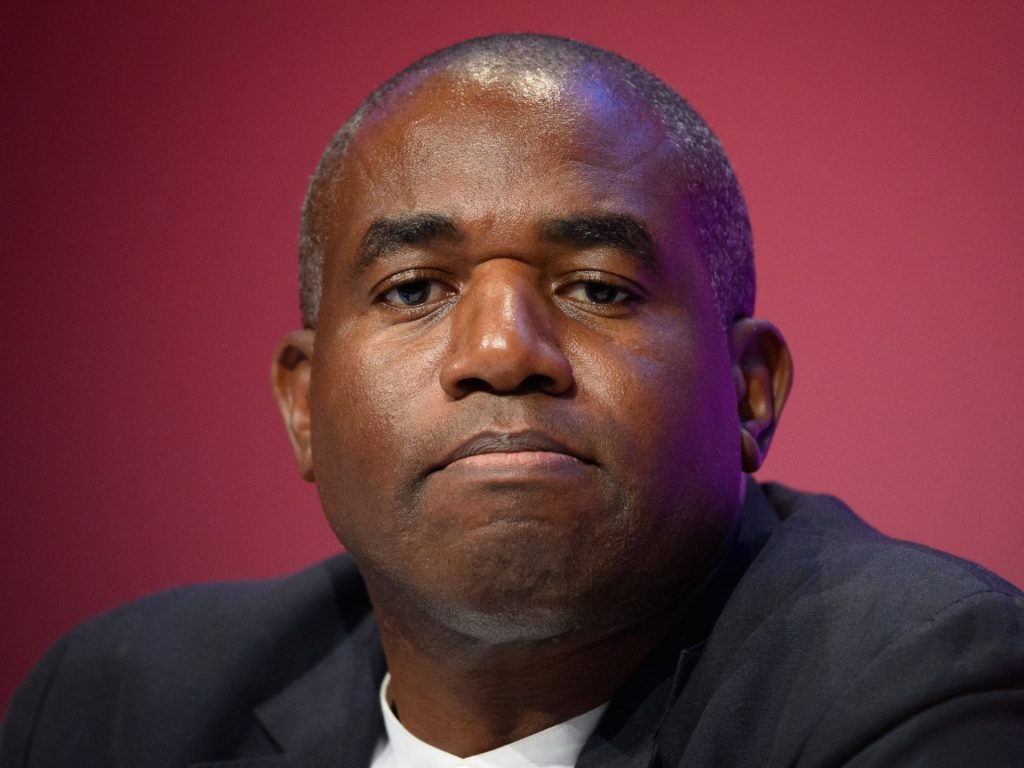

From the Conservatives came Michael Gove, a long-standing backer of Brexit, alongside the former Tory leader Michael Howard and the former Tory chancellor Norman Lamont. From the opposition Labour Party came senior members of Keir Starmer’s shadow cabinet, including David Lammy, the shadow foreign secretary, and his colleagues covering defence, trade and the Cabinet Office.

Senior figures from science and industry were also present, including John Bell, the Regius Professor of Medicine at Oxford University who had led the development of the AstraZeneca Covid-19 vaccine, and the chairs of global companies including the pharmaceutical multinational GSK plc (formerly GlaxoSmithKline) and telecoms giant Vodafone. Supporting the discussion with technical know-how were senior former Whitehall mandarins, including Olly Robbins, who had negotiated Theresa May’s failed Brexit deal, and Tom Scholar, the former permanent secretary at the Treasury who was sacked on the orders of Liz Truss at the outset of her disastrous premiership.

It was precisely the kind of discussion that has been so often absent from the Brexit debate since 2016. Given that “in-out” referendums are by their nature binary and Europe had been a politically divisive issue in British politics for decades, it was perhaps naive to think it would be any other way; but almost seven years after the Brexit process began, the Ditchley discussion was a genuine attempt to begin to detoxify that debate. It was based on the premise that rebalancing the conversation away from the political towards the pragmatic will be an essential prerequisite for progress.

And that applies to whichever government comes to power after the 2024 (or early 2025) general election. Very soon after taking office, the new occupant of Downing Street will need to start to prepare – alongside industry and civil society – for the five-yearly review of the implementation of the EU-UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA), which is a legal requirement of the deal. If there is political will, the review will provide the first major opportunity to reconsider – on the UK side, at least – what Brexit means, and ask whether the initial sovereignty-at-all-costs approach to leaving the EU pursued by the Johnson government is really the right one.

The reaction to the newspaper report of the Ditchley meeting from a caucus of hard Brexiters was itself indicative of just how difficult this will be, and how much political leadership will be required to move Britain away from the reflexive betrayal narrative that is deployed by those who want to defend the hardest possible Brexit at any cost. “Secret plan to unravel Brexit” was how the Daily Mail characterised the event. Nigel Farage took to social media to warn that “the full sell-out of Brexit is under way”, adding, “This Tory Party never believed in it.”

David Frost implied something similar, contending that his Brexit deal didn’t “need ‘fixing’, it just needed a Conservative government ‘to fully and enthusiastically embrace its advantages’”. David Jones, the deputy chairman of the European Research Group (ERG) of Eurosceptic Tory MPs that had become the arbiters of Brexit faith during the crucial negotiation years of 2018–20, added darkly that: “It’s hard to believe that closer constitutional links were not on the agenda.”

And what if they were? The idea that moving any closer to the EU is a “sell-out” of the Brexit ideal is designed to put a straitjacket around any conversation about options for the future. The “closer constitutional links” of which Jones warned are only sinister if you regard any trade-off on sovereignty as an act of surrender, rather than a balanced calculation of where the national interest lies. We can – and should – argue about the balance of those trade-offs, but such extreme reactions are designed to shut down the space for discussion.

Frost’s continued assertion that the current Brexit settlement would be brilliant if only it was implemented more enthusiastically ignores the out-turn of the current low-ambition trade deal. Regardless of all the warnings in the economic data, the Brexiters’ last argument is that the revolution would surely succeed, if only it was pursued more zealously.

And yet for all the talk of “Brexit opportunities”, seven years after Brexit there is still a worrying haziness about what precisely those opportunities might be. General allusions to the UK’s prospects in the industries of the future, like gene editing or artificial intelligence, do not amount to a strategy. Unless you count restoring crown stamps on pint pots, of course. This is not to say that Brexit cannot provide opportunities to do things differently, which may have upsides for some sectors of the economy, but those upsides will always have to be weighed against the downside costs of building back barriers to the market that takes half the UK’s trade.

Based on the experience of the first two years properly outside the EU, the numbers are not encouraging. The level of UK goods trade is around 10-15% below what it would otherwise have been, according to the Bank of England. Business investment has flatlined since 2016, in part because of the uncertainty generated by the prospect of perpetual regulatory upheaval.

Brexiters continue to promise this will deliver a future crock of gold at the end of the deregulatory rainbow, but in the meantime, Jonathan Haskel, professor of economics at Imperial College London, and Josh Martin at the Bank of England calculated that Brexit caused a 10% hit to business investment in 2022, which equates to an estimated reduction in GDP of £29bn – or £1,000 for every household. And they warned that the pain would not stop there. Their analysis suggested that this figure “would grow over time unless business investment recovers to where it would have been”.

The current trade and investment numbers are surely grounds for a renewed discussion on the balance of Brexit. The current settlement is not – as some Brexiters would have us believe – an expression of the one true Brexit, a static, inviolable covenant that must be defended at all costs. And the polls now suggest the British public knows this perfectly well. When the TCA came into force in early 2021, the public was still split roughly 50:50 about the merits of Brexit, but two years later UK opinion had shifted to nearly 60:40 in favour of rejoining the EU if there was a referendum tomorrow.

But while the public discourse on Brexit is shifting, particularly on the economic consequences of leaving the EU, the political conversation remains paralysed by old fears and animosities.

In the final days of his premiership in July 2022, as Boris Johnson defended the record of his government, it was to Brexit that he immediately returned, taunting Keir Starmer at the dispatch box for trying to “overturn the will of the people” during the Theresa May era and reminding him that the outcome was the biggest Tory election victory since 1987, smashing down the Labour Red Wall, and turning “Redcar bluecar”. And it was all down to Brexit, said Johnson.

“Some people will say, as I leave office, that this is the end of Brexit,” he added, pausing for effect. “Listen to the deathly hush on the Opposition benches! [That] the leader of the opposition and the deep state will prevail in their plot to haul us back into alignment with the EU as a prelude to our eventual return. We on this side of the House will prove them wrong, won’t we?”

A full nine months after Johnson left office, and despite the debacle of the Truss premiership, the reaction to the news of the cross-party Ditchley meeting was straight out of the same playbook – to stoke the fear that “the rejoiners and the revengers” were plotting to reverse the result of the 2016 referendum.

But as the worm of public opinion continues to turn, there should be less and less reason for Keir Starmer to maintain a “deathly hush” over Brexit. He has made clear that he will not look to rejoin the EU, the single market or a customs union with the EU. This shuts down large areas of potentially profitable discussion about where Brexit could go. But still, with the right political leadership, even its current self-limiting position still leaves space to sell a better Brexit than we have now. Because those very same “Red Wall” manufacturing heartlands that Johnson was so jubilant about stealing from Labour face some of the biggest potential downsides of Brexit.

Far from “taking back control”, the UK has in fact been left in a state of limbo by Brexit. Moving on means that those, like Johnson or Farage, who were allowed to define Brexit in its current form, should not be granted a monopoly of wisdom about what Brexit might mean in the future.

Talk of “selling out” or “betraying” Brexit – by which they mean the Dad’s Army version of Brexit – is an attempt to close down a debate about the scope of the UK’s relations with Europe. This is a debate the UK urgently needs to have. The last seven years have poisoned British politics, unsettled the foundations of Britain’s unwritten constitution, curtailed trade, rattled investors and tarnished the UK’s reputation abroad as a pragmatic power that can be trusted.

The coming general election could provide a political inflection point. The Northern Ireland Assembly will hold its first consent vote in 2024 on whether to continue to accept the newly refurbished post-Brexit trading arrangements. And after 2025, the low-ambition EU-UK trade deal agreed by Johnson is also up for review, giving the UK a chance to improve terms with the economic bloc that takes nearly half the UK’s trade. All these provide potential footholds to rebuild broken relationships, but only if there is sufficiently brave political leadership to shift the Brexit debate away from toxic notions of “betrayal” and back on to the economic wellbeing of the nation.

It’s time to think again about Brexit by taking an approach based on the facts, not fallacy and fantasy. Both Conservatives and Labour continue to set red lines over the UK’s future relationship with Europe – no membership of the customs union or EU single market – while airily promising that the disadvantages of leaving the EU will be massaged away over time. More likely, if those red lines do not at least turn pink, the opposite will be the case as the EU finds other places to do business with; other universities to send their students to; other musicians to play in their orchestras; and other nations through which to thread their supply chains and build security and energy alliances.

The process of honestly interrogating Brexit trade-offs does not have to be a counsel of despair. It could just as easily be a wake-up call, helping the UK identify structural shortcomings at home, as much as deciding where to set the cursor on the relationship with the EU. But time is of the essence.

The UK’s diplomatic and trading relationships with Europe have a half-life. Based on the current rate of attrition, many will not survive another seven years of disengagement and decay. The time for a Brexit reboot is now.

This is an edited extract from What Went Wrong with Brexit, by Peter Foster (Canongate)