With the season of mists and mellow fruitfulness upon us and the government pressing on relentlessly with its prime-ministerial knockout

championship of dimwitted panto villains, it feels like a good time to crank up the heating and sit down to enjoy the show. Well, it would be if it weren’t currently more economical to keep warm by burning actual fivers and the safety, integrity and future of the country weren’t in the hands of a squabbling collection of vacuous nitwits.

Instead, last weekend I zipped up an extra hoodie and set about a physical task that I hoped would help keep the autumn chill from my old bones:

rearranging the books on my shelves.

Mostly this task involved taking down a book, sitting cross-legged on the floor, reading it for 20 minutes and replacing it exactly where it was on the

shelf, a level of feckless distraction that prevented constructive progress. One thing I did achieve, however, was reacquainting myself with an aspect of

my book hoarding that’s sometimes as fascinating as the books themselves.

An occasional bonus of acquiring a secondhand volume is that you’ll often

find traces of its previous owners, even just a name written in the top corner of the title page. Take my copy of a miniature edition of Dr Johnson’s Dictionary published around 1820, for example. Written in ink faded to brown on yellow paper is “Eliza Wallis, Salford, Dec 16, 1833” along with a

couplet from a poem by George Herbert: “Let thy mind’s sweetness have its operation, upon thy person, clothes, and habitation”.

From the moment I saw that inscription I’ve wondered who Eliza Wallis was, what became of her, what those particular lines of Herbert’s meant to her that she chose to inscribe them in her dictionary on a wintry Lancashire Monday almost two centuries ago.

There’s extra poignancy about the pair of inscriptions in the front of my copy of The Old Road by Hilaire Belloc, a book first published in 1911 that describes the journey between the ancient pilgrimage centres of Winchester and Canterbury.

“D.A.B., from R.R.W, 15.XI.15” is pencilled on to the frontispiece, under which is written in a shakier hand, “G.S.B., from D.A.B, 25.XII. 79”.

Two dedications, 64 years apart, made to and from the same person. Maybe D.A.B. was a young man in 1915, maybe he was heading off to war and the book was a gift intended to remind him of home. Two-thirds of a century later an elderly D.A.B. passed it on to someone else as a Christmas present,

adding an inscription that echoed deliberately the format of the original.

To part with such a book after keeping it for so long, well, somebody must have meant a great deal to D.A.B. That we all might have in our dotage a person so dear to us we’ll willingly gift them a long-held treasure from a

lifetime ago.

Published the same year that D.A.B. was presented with his Belloc was my

copy of 1914 and Other Poems by Rupert Brooke. Brooke died of septicaemia on a French hospital ship in the Aegean on April 23 1915 at the age of 27 and the collection was rushed into print so quickly that my copy is dedicated “To dear Judith from her Father and Mother, July 20 1915”, not quite three months after the poet’s death. The parents also appended the phrase “Inheritor of unfulfilled renown” to their inscription, words Shelley had used in reference to Keats, Chatterton and other poets who died young.

It seems that Judith was an admirer left bereft by the news of Brooke’s death, as pasted beneath the dedication is a sonnet titled “In Memoriam Rupert Brooke” clipped from a newspaper. Attached inside the front cover is another cutting, a heartfelt appreciation of the poet published a week after his death that she had carefully preserved until she was given the slim volume of his verse.

I can only wonder at the lives of Eliza Wallis, D.A.B. and Judith. It’s a strange feeling to share the same intimacy they enjoyed with the same volumes all these years later, as if some kind of connection has been established. I’m just a temporary custodian of these books, one day they’ll all belong to someone else, the inscriptions anchoring them to those previous owners in a way that only emphasises the transience of my possession of them.

The inscriptions are too vague to find out more about these particular individuals, even Eliza Wallis despite having a date and location. But sometimes it is possible to add depth and context to the bare inscriptions found in old books.

Four years ago I wrote in these pages about Helen Grant, who in 1936 had been presented with what’s now my copy of Burns’ poems by the Brechin

Burns Club for excellence in reciting his work. Helen became a leading light in the Brechin branch of the Communist Party, moved to London and was killed in a train crash on her way to work one foggy autumn morning in 1947 at the age of 23.

Helen Grant is just a name inside a book that over the course of 80-odd years has found its way to me, yet knowing her story makes that book extra special to me somehow, as if I’m preserving her memory by taking custody of it. Knowing her story lends an extra dimension to possessing her book.

Which brings me to another volume I opened during my feeble attempt at shelf reorganisation, one that contains mysteries I’d dearly love to solve. I

unearthed my 1930 edition of HV Morton’s travelogue In Search of Scotland while rummaging in a junk shop on the Isle of Wight a few years ago and there are two reasons why I have been puzzled by it ever since.

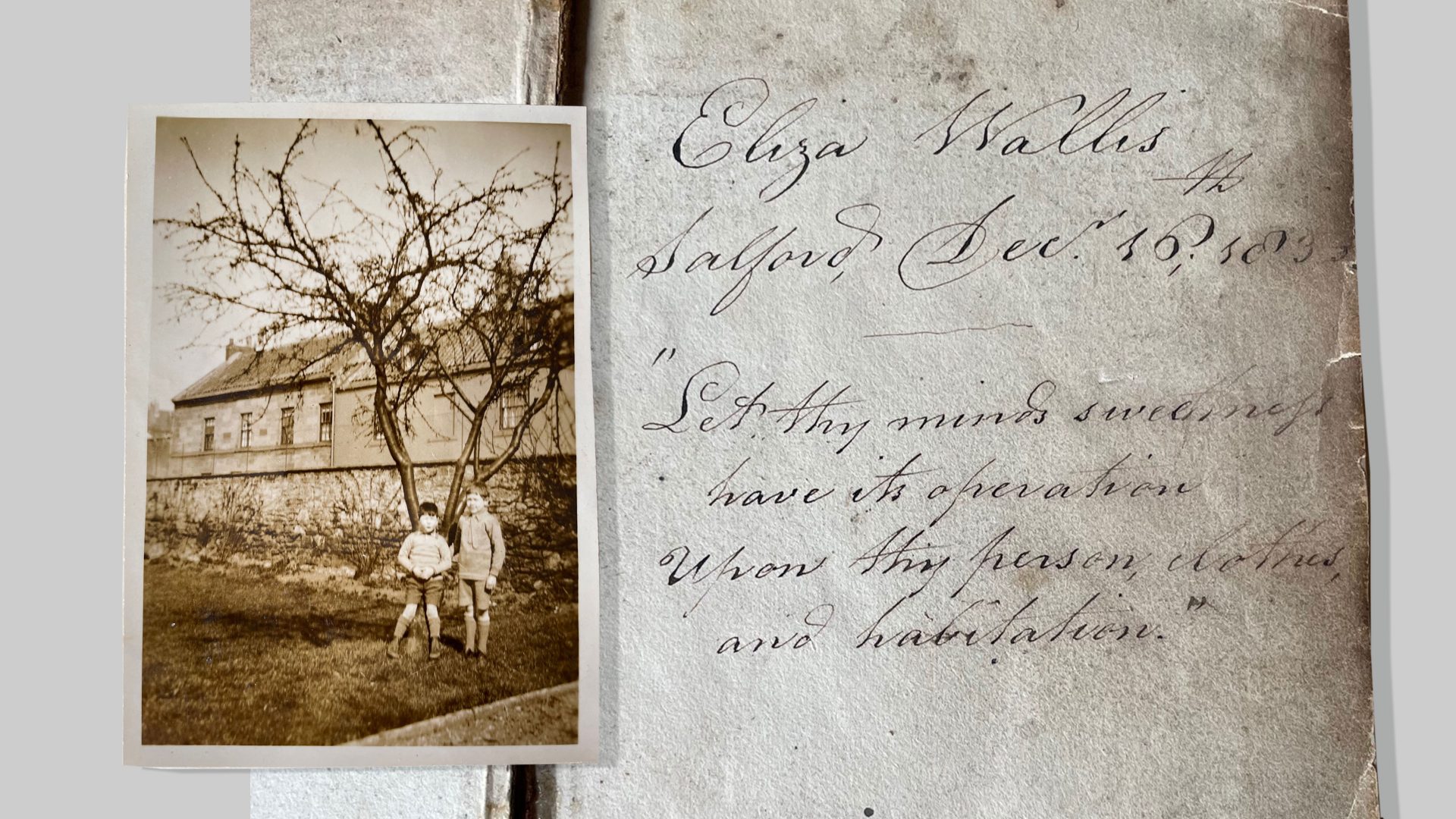

The first thing I noticed on opening the book was the photograph glued opposite the title page, a sepia image of two small boys posing under a gnarly tree in what looks like a walled garden with a couple of houses in the

background. The smaller of the pair is leaning back against the trunk, has

managed to blink at the precise moment the shutter snapped and has his lips pursed as if he’s in the middle of saying something. The older boy stands beside him a little formally, wearing a necktie over his sweater and with his hand placed in the small of the younger boy’s back. He’s looking straight at the camera and smiling with a grim weariness that belies his youth.

There are no clues as to who these boys might be or why their photograph is stuck inside a 90-year-old travel book about Scotland that ended up in a box at the back of a damp junk shop on the Isle of Wight. There’s not even an owner’s name on the flyleaf.

The picture has the feel of a holiday snap and perhaps the location is significant. Either way, something was important enough about this

particular photograph and this particular book to prompt somebody many years ago to affix one inside the other. Not just tuck it in between the pages, actually attach it with glue. It was intended to stay there, a homemade frontispiece to a book that meant something to someone.

It took me a little longer to notice the second mysterious thing about my copy of In Search of Scotland. Near the front is a photograph of Auld Reekie, but I’d had the book for quite a while before I realised I could see ink coming through the photograph, as if from something written on the previous page. There was nothing written there though, just the printed title of the book. Eventually I realised that two pages had been stuck together and whatever I could see through the photograph had been deliberately hidden from view.

Fortunately the glue was so old it was a straightforward task to separate the pages without damaging the book and see whatever had been written then concealed.

It was names.

A dozen of them, all women, all in different hands. They’d each signed the

page, then somebody had glued it closed with the intention of hiding the

inscriptions forever. Margaret Hall, Doris Hall, Sheila Hatchell, Cecilia

Cleary, Peggy Lamb, M Stobbs, Dorothy Preston, Dorothy Snell, Joan Hegarty, Marjory Wood, Margaret Lawson and Marie Henderson had all passed the book between them, carefully written their names on a blank page, glue had been brushed over them and the book closed until it dried.

I’ve tried to trace them. Some are possibly connected to a convent school in Berwick-upon-Tweed in the early 1930s, but that’s as far as I’ve got. Who were they and what bound them together to write their names inside this particular book, only to hide them for ever? And why hide them for ever?

There’s something almost ceremonial about it, a pact maybe, perhaps some kind of solemn swearing of friendship expressed through this particular book. And are they connected to the boys in the photograph? I would dearly love to find out but I doubt I ever will.

Books are by definition repositories of stories, but some books are portals to stories outside their printed words. Layers of narrative added by owners, tiny fissures in time that leak hints of the same intimacy between book and

reader that we, the latest temporary custodians, are privileged to share.