The rare, the lost, the extinct, will always fascinate, all the more so when it pertains to the human – a language no longer spoken; a custom; a way of life that has died out.

Such cases appeal to our mythologising instincts, and every so often they resurface in an auction of artefacts, an exhibition, a book or film. And nowadays they appear on social media, where snapshots of times past and accompanying text regretting their absence are only ever a scroll away.

The world of the 18th-century Italian castrati is different. Who would wish for its return? Yet the idea of these vanished voices continues to intrigue us.

At Handel Hendrix House in London, a portrait is displayed of one of the greatest castrati of his day, Francesco Bernardi, better known as Senesino (1686-1758). It is part of a bijou exhibition that celebrates the 300th anniversary of the first performance of Rodelinda in 1725 at the King’s Theatre in the Haymarket, an exhibition staged in the home where George Frideric Handel composed the opera.

Senesino is depicted in character as Bertarido, his role in the premiere of Rodelinda. The castrato looks heroic, capped and caped, dressed in a pearlescent dusky pink tunic, braided and fringed; he is at the point in the opera where he will sing its most famous lament: Dove sei, amato bene? Alongside this flattering portrait are several caricatures that present a less favourable picture of the singer.

Handel was instrumental in popularising Italian opera in London through his directorship of the Royal Academy of Music, for which he wrote his operas and hired his singers. The castrati who visited and worked for him were exclusively Italian, for it was only in Italy that the practice of removing a boy’s testicles between the ages of eight and 10 to preserve the purity of their unbroken voices became embedded for almost two centuries.

A number of factors coincided to bring this barbaric custom about: the Vatican initiated the trend by importing falsetto singers from Spain, then introduced its first Italian castrato into the Papal Choir in 1599; the public’s enthusiasm for the castrati’s liturgical singing in Rome led to their widespread recruitment in cathedrals and churches throughout the city states, while a succession of papal decrees restricted the roles of women in the church and on stage.

As music evolved to capitalise on the castrato voice with virtuoso arias in secular productions, new theatrical opportunities offered the castrati a less cloistered way of life, and the riches they amassed made the operation attractive to poorer families. By the early 1700s, as many as 4,000 Italian boys a year went under the knife, though only a fraction of these achieved celebrity on the stage.

The caricatures of Senesino at Handel Hendrix House emphasise the effect that castration and training had on the singer’s anatomy, and the ambivalent attitude towards these singers abroad. Like all castrati, Senesino trained intensively for five or six years at the conservatoire, practising inhalation and exhalation exercises and expanding the ribcage, resulting in a distinctive barrel chest which, alongside their tall stature, beardless complexion and physique prone to fatness, led some commentators to compare them to capons (castrated chickens).

Many were the eulogies for castrati performances, finding in their voices “the music of angels”, “the supernatural” and a clarity and richness that “embodied the trinity of man, woman and child”. Many, too, were the disparaging remarks on their appearance: “When you meet them in a gathering you are completely taken aback, on hearing these colossal men speak with a tiny childlike voice,” wrote Charles de Brosses, president of the Dijon parliament, in his letters 1739-1740. His compatriot, Pierre-Jean Grosley, agreed. “I would always have preferred an ordinary voice in an ordinary body to the most marvellous musico…”

Senesino was invited to London by Handel in 1720, and the Italian went on to sing in as many as 17 of Handel’s operas, but his relationship with the composer was tumultuous, and in 1733 Senesino joined a rival opera company, The Opera of the Nobility.

It’s hard to imagine today the extent to which competitiveness shaped opera, both among audience members (dressed to be seen) and between the London opera companies and the castrati themselves. The singers even duelled against the musical instruments that accompanied them, showing off the notes they could achieve and the duration for which they could sustain them. Such peacockery was part of the swaggering flamboyant extravaganza of baroque theatre.

When Senesino left London for good in 1736, he retired to a fine townhouse in Siena, furnished in the English style, where he liked to drink tea. In 2019, a Meissen Böttger stoneware teapot and cover (c.1710-13) came up for sale at Bonhams in London. The teapot had belonged to Senesino, and his ownership may have contributed to the staggering sale price it achieved at auction: £35,062.50.

The second celebrated and revered Italian castrato working in London at the same time as Senesino was Farinelli. His name is more familiar today, through the 1994 eponymous film and the 2015 play at the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse.

When the castrato arrived in the capital in 1734, he was wildly successful, but he never performed for Handel, having joined the opposing Opera of the Nobility. The striking posters advertising the opulent but inaccurate biopic, Farinelli, in 1994 remain memorable, but the film illustrated the difficulty of recreating the castrato’s voice, which was represented by a digital twinning of a countertenor with a soprano.

In Claire van Kampen’s play, Farinelli and the King, the role of Farinelli was divided between an actor and a countertenor and took, as its starting point, the true story of Farinelli’s engagement by the Queen of Spain to sing at the Spanish court to cure her husband, King Philip (Philippe) V of his depression. “Every night, I sing eight or nine arias,” Farinelli wrote in 1738. “I never rest.” He lived in Spain for 22 years, serving the new king on Philip V’s death.

Van Kampen, a composer and music director, explained why this tale had appealed to her: “My play is the relationship between two men who have been unnaturally elevated to kingship; both have been damaged in the process… the play is also about the impact that an extraordinary voice makes on a mind diseased.”

The art of the castrato disappeared as musical tastes changed, and performances shrank back to the Vatican, which employed them until 1903. Only two recordings exist of a castrato, and these belong to a middling chorister by the name of Alessandro Moreschi, the last castrato, whose fossilised voice was captured by the Gramophone Company of London in 1902 and 1904.

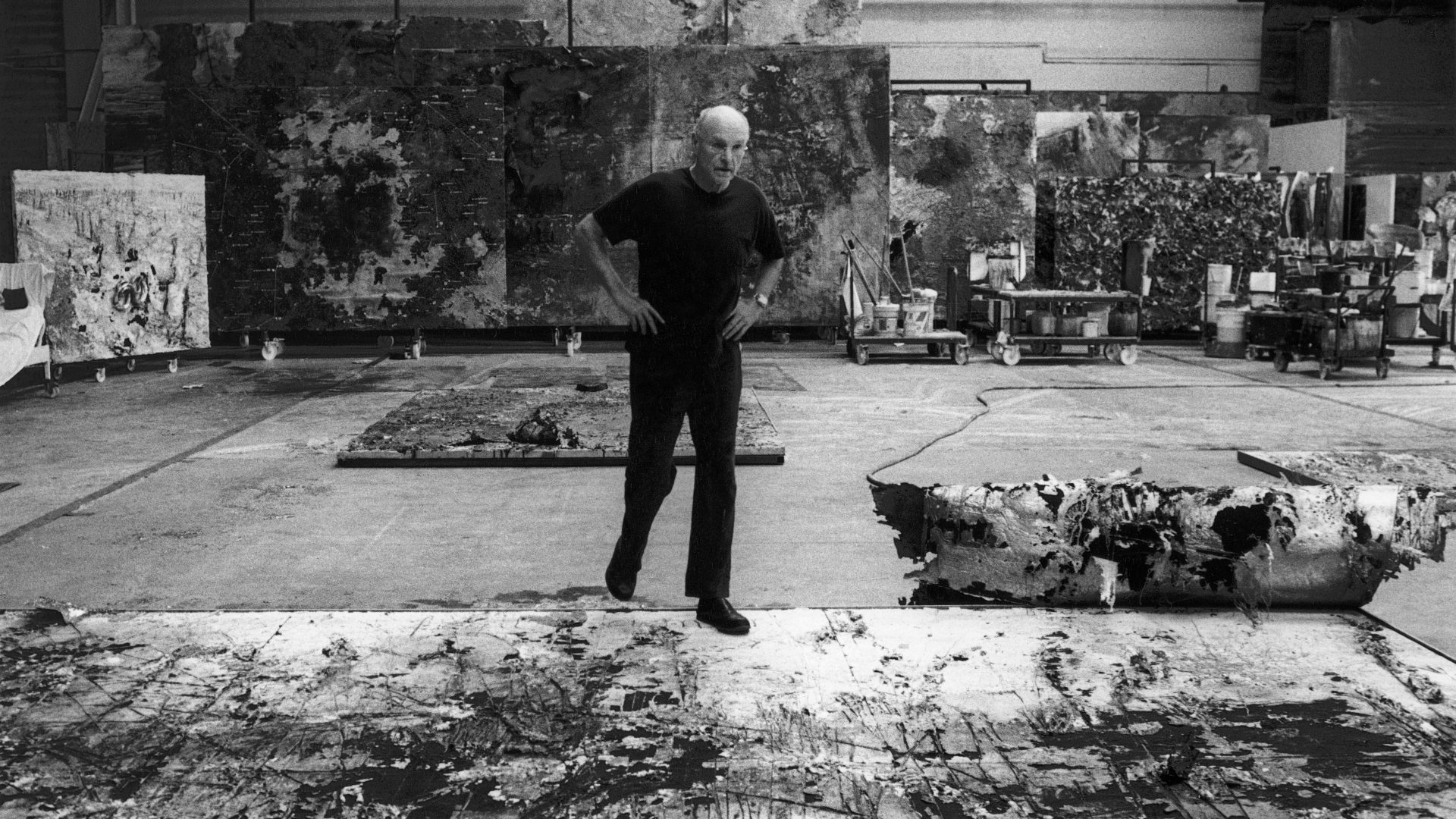

I was reminded of Moreschi at the Leigh Bowery! exhibition at Tate Modern. This retrospective celebrates the life of the British performance artist (1961-1994) who transformed his 6ft 3in body by strapping up his penis beneath a merkin, binding his chest to suggest breasts, wearing a gimp mask and adding protuberances to padded costumes, creating post-modern shapes that were barely human.

In the exhibition catalogue, one of Bowery’s circle, Ron Athey, describes dancing to a cut-up recording of the last castrato at the ICA. It is a relic of the musical past resurfacing in acts of contemporary performance and a union of outsiders who shocked, delighted and appalled in the name of art.

Rodelinda runs until July 6, 2025 at Handel Hendrix House, 25 Brook St, London W1K 4HB