When Charles Baudelaire’s collection of poems Les Fleurs du mal (The Flowers of Evil) was published in France in 1857, it provoked outrage among critics and public alike. In it were poems teeming with angels, demons and Satan himself.

The consequence? Both poet and publisher were prosecuted and fined, and six poems were censored for “offending public morals”. If he were alive today, Baudelaire could not have wished for better publicity. A revised edition was brought out four years later, but by the time the six banned poems reappeared in Les Épaves (Wreckage) in 1866, Baudelaire was afflicted with illness and disease, succumbing to an early death at the age of 46.

A neatly dressed dandy living in squalor, the poet was, according to Willis Barnstone in his forward to Baudelaire’s selected poems, “King of a rainy kingdom, companion to thin Parisian prostitutes keeping warm by clutching sticks of fire to their breasts”. He was the real deal, decadent in word and deed, contracting syphilis in the Latin Quarter, developing a dependency on opium, and penniless for most of his life.

Intriguingly, flowers scarcely get a mention in his verse. Baudelaire had not a horticultural bone in his body. When asked by critic and editor Fernand Desnoyers to contribute to an anthology on nature, he replied: “I will never believe that the soul of the gods dwells in plants, and even if it did, I care little for it, and I would still consider my own soul a much higher good than that of sanctified vegetables.”

Strongly present through his work is an evocation of scent, from the coconut oil, musk and tar wafting through La Chevelure (a poem dedicated to his mistress Jeanne Duval’s hair) to the fragrance of green tamarinds blending with sailors’ sea shanties in Parfum Exotique (Exotic Perfume).

Böse Blumen (Evil Flowers) is an exhibition of 120 works (paintings, sculptures, videos, prints and installations) inspired by Baudelaire’s poetry, currently on show at Scharf-Gerstenberg Art Museum in Berlin. The museum, formerly the Egyptian Museum of Charlottenburg, makes an aptly shadowy sepulchral setting.

You enter through the columned Temple Gate of Kalabsha, and one of the first works you see is Odilon Redon’s charcoal Fleurs du Mal

(c. 1890), part of the museum’s permanent collection and the impetus behind the exhibition. Redon never met Baudelaire, but he made a series of drawings in response to the poems; some displayed in a nearby vitrine.

Early in his career, Redon preferred to work in black and white (his noirs) using ink and charcoal to produce “dense, powdery surfaces”. From these, he conjured up disembodied heads, giants, cyclops and winged creatures. “As a child, I sought out the shadows,” he recalled. “I remember taking a deep and unusual joy in hiding under the big curtains and in the dark corners of the house.” In Fleurs du Mal, an ambiguous figure holds a bloom beneath their tipped-up chin. Realised in soft grey tones, the drawing has a chimeric quality, the figure drifting between consciousness and daydream.

Böse Blumen encompasses art dated well before the poems, as well as those from the 21st century. As many of the exhibits come from collections in Berlin, there are notable absences from further afield; the curation is oddly framed: is the show investigating the themes of Les Fleurs du Mal (in which case, why the flowers?) Or is it a looser exploration of the aesthetics of beauty, eroticism and evil?

At times, I felt I was wandering through an eccentric flower show. The 1790 etching Planter of Men from Paris is a regular penis-fest: winged vulvas flutter round a green-haired tree rooted and fruited with phalluses, sure to bring a smile to the most prudish of lips. Pornography was certainly Baudelaire’s bag, but comedy?

The sense of life existing in the darkness of the tomb is evoked in the set of 18th-century watercolours by Barbara Regina Dietzsch. A flowering cactus, a celery and a thistle are pinned to pitch-black backgrounds, trapped in narrow frames. In the 2019 photographs by Ulf Soltau, plant life struggles to survive the concrete gravel gardens of suburbia.

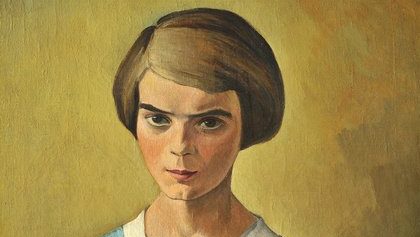

The crush of dark emotions lurks in Alexander Kanoldt’s painting of Angelina (1935) and Christian Schad’s portrait of Ludwig Bäumer (1927). Angelina, with her neat bob, Madonna-blue dress and bouquet of flowers seems, at first glance, an innocent, but her sombre gamine eyes hanging beneath fierce brows and her knowing adult look suggest passions beyond her years.

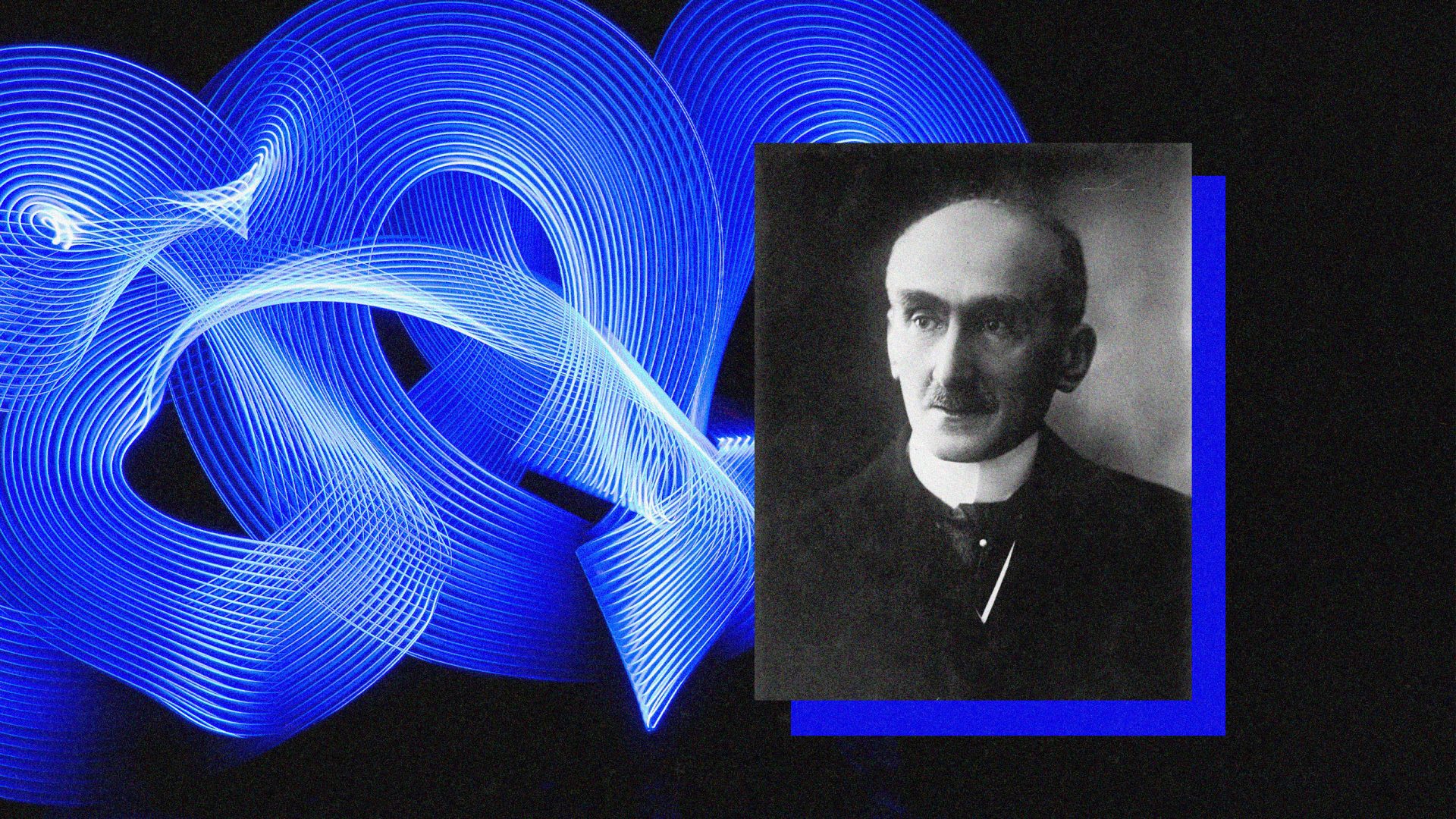

Ludwig Bäumer sits solidly in the picture frame, the epitome of respectability, dressed in his brown-study jacket and waistcoat, but his calm placid stare is upended by the strange mirrored wall behind him, and the petalled phallic flowers encroaching in the background; their arched stamens echoing the curved scar on Bäumer’s cheek. A writer and communist living in Berlin and Munich, Bäumer committed suicide a year after the portrait was painted.

Baudelaire consorted with rule-breakers, but not with those breaking up Paris. A dedicated flâneur, he mourned Baron Haussmann’s uprooting of the capital’s twisting medieval streets in favour of broad, straight boulevards, a subject treated in his poem The Swan. In The Little Old Women he describes the octogenarian Eves who “creep along”, “their eyes still pierce like drills, shining like puddle water in the night”.

Albert Birkle’s 1923 canvas Little Old Women is a serendipitous match for Baudelaire’s poem. Five elders stooped and wrapped in shawls, clutching walking sticks, turn their watery gaze towards us or towards the water under the bridge on which they stand.

This work is exhibited in the gallery’s Disease and Decay section, a theme marvellously captured in – of all things – a fire extinguisher dropped into the sea by artist Peter Bux, who later recovered it. Residual Risk is displayed in a glass case, encrusted with petal-like shells, an artistic response to the 2011 tsunami in Fukushima, Japan, where Gloria fire extinguishers in hotels were ineffectual against the rising waters.

Beauty found in sickness, horror and death make hardy shoots pushing out from the past, into the present and the future in Böse Blumen. On illuminated screens are floating planets with obscene purplish flared horns – magnified Covid virus cells, AI-generated; against sunny skies, a giant mushroom cloud of atomic dust bursts flamboyantly over Nagasaki; a photographic sequence captures hungry black clouds and blazing fires consuming New York’s World Trade Center. These create a “fusion between the sordidly realistic and the phantasmagoric”, which TS Eliot had so admired and counted as one of Baudelaire’s achievements.

Böse Blumen is an enticing theme, but I missed the political and historical contexts in which to position Baudelaire’s poetry; I missed the paintings of Delacroix, spiced with voluptuous women lounging languorously in their harem (Femmes d’Alger) and the paintings of Baudelaire’s walking companion, Édouard Manet; many other notables were absent, from the illustrations of Henri Matisse to the paintings of Anselm Kiefer.

Most of all, I missed heavy velvet curtains and perfume and the sense of intoxication, from unctuous oils and opium to wine, rubies and pearls, the lure of bohemian excess. I found beauty, but I wanted it balanced on a knife-edge. What we do get from this enigmatic show is a venture into the tomb; as I leave, I pass the perforated mannequins of Bernard Schultze; beauty and decay entwined.

Böse Blumen is at the Scharf-Gerstenberg Art Museum, Berlin until May 4, 2025