As Europe reels from the sudden gear shifts of the US government, it is tempting to see Donald Trump as an outlier, isolated in his endeavour to reshape the world order. But while Trump’s tariffs agenda has mixed support even among Americans, its radicalism has been enabled by a restlessness and yearning for change that is clearly present in Europe, too.

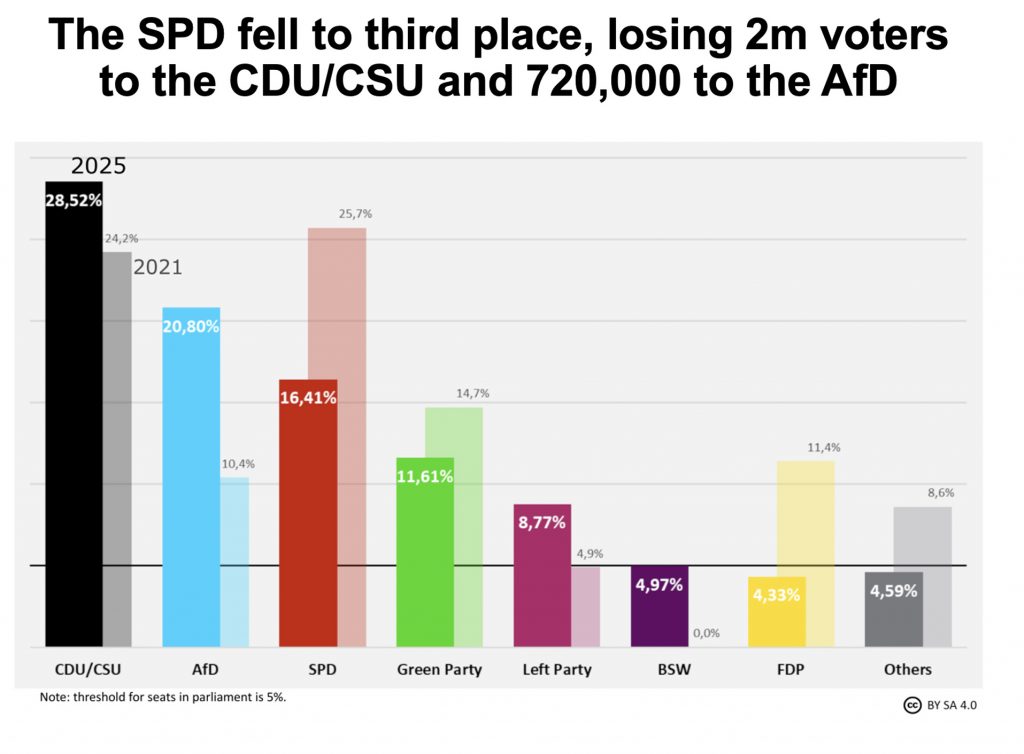

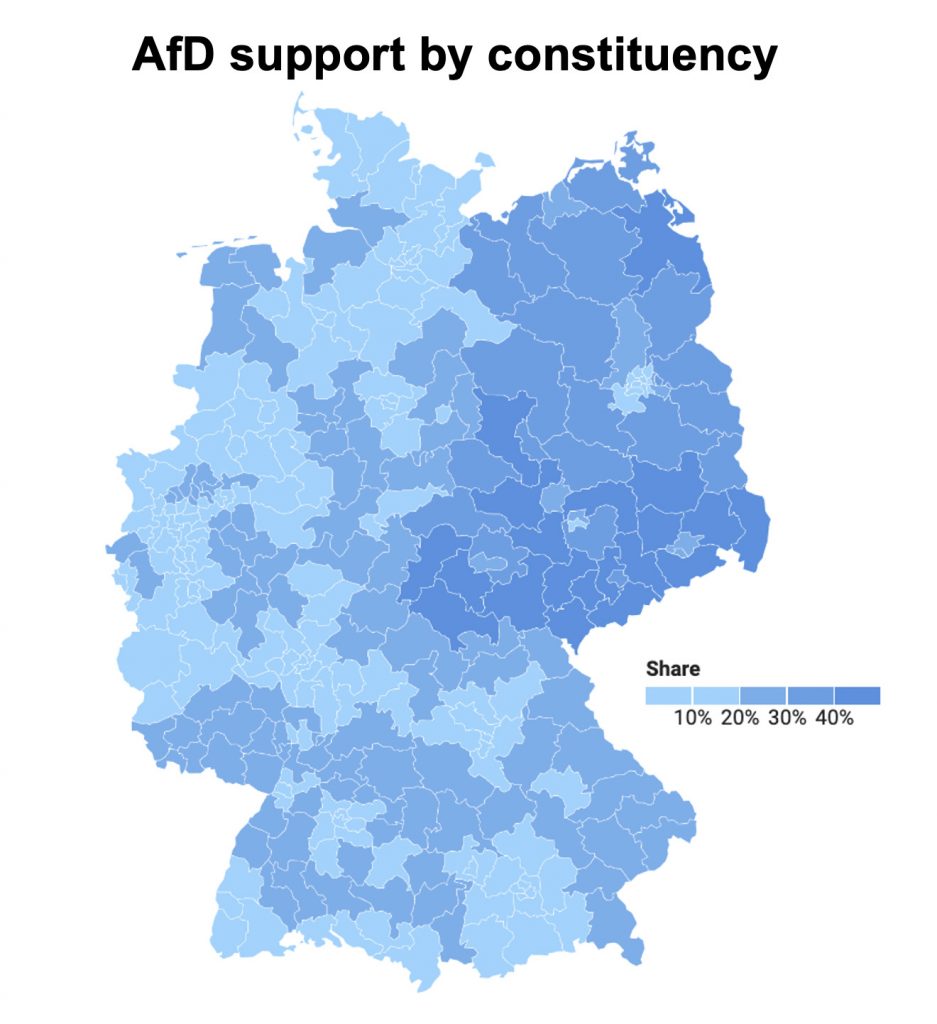

Many progressives took heart from the victory of Labour and Keir Starmer – for whom we have both worked – last July. There was some relief, too, at the election of Freidrich Merz’s CDU in Germany, which might have beaten the Social Democrats but at least denied success to the far right AfD and its troubling political agenda. Yet restlessness with “politics as usual” – seen to be offering the same tired answers – is gaining pace rather than abating.

Voter research that we conducted immediately after Germany’s election, for a project on behalf of the US-based Progressive Policy Institute, offered few crumbs of comfort. We asked voters who had previously supported Olaf Scholz’s Social Democrats why they had changed their vote. The answers sounded familiar to us from our campaigns for Labour in the UK, and echoed views we had heard in the US battleground states after the US election last autumn.

One woman in west Germany spoke for many: “The middle class has to struggle more and more to make ends meet. Salaries are not rising, but prices are.” Another told us: “I don’t like opening my mailbox any more. Bills have got more and more expensive.”

The stories we heard were often depressing, told by people who feel fearful, and neglected. When asked to bring along an object to sum up life in Germany nowadays, an east German man showed us “a squeezed-out tube of toothpaste. We feel squeezed out – financially, emotionally.”

Others brought burnt-down candles, rubbish bags, and a cloudy glass of water plus a pair of dark glasses, both chosen to make the same point: “It’s hard to see where the country is going nowadays.”

Of course, the feeling that life is getting harder is not new. It’s a story we have heard many times before in German industrial heartlands, the English Red Wall, or the American Rust Belt. As one SPD to AfD switcher told us, “We’re not producing anything any more. A steel mill near where I live was sold and nobody from the SPD cared about it.”

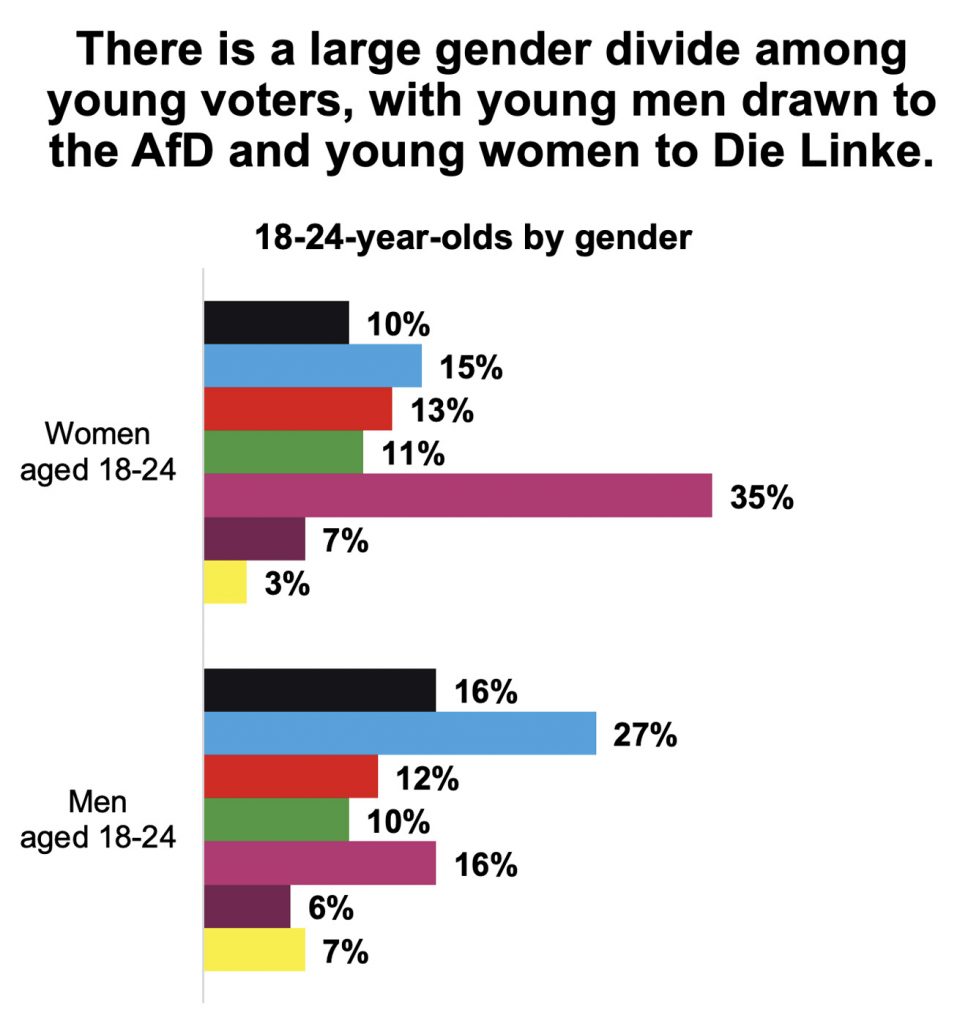

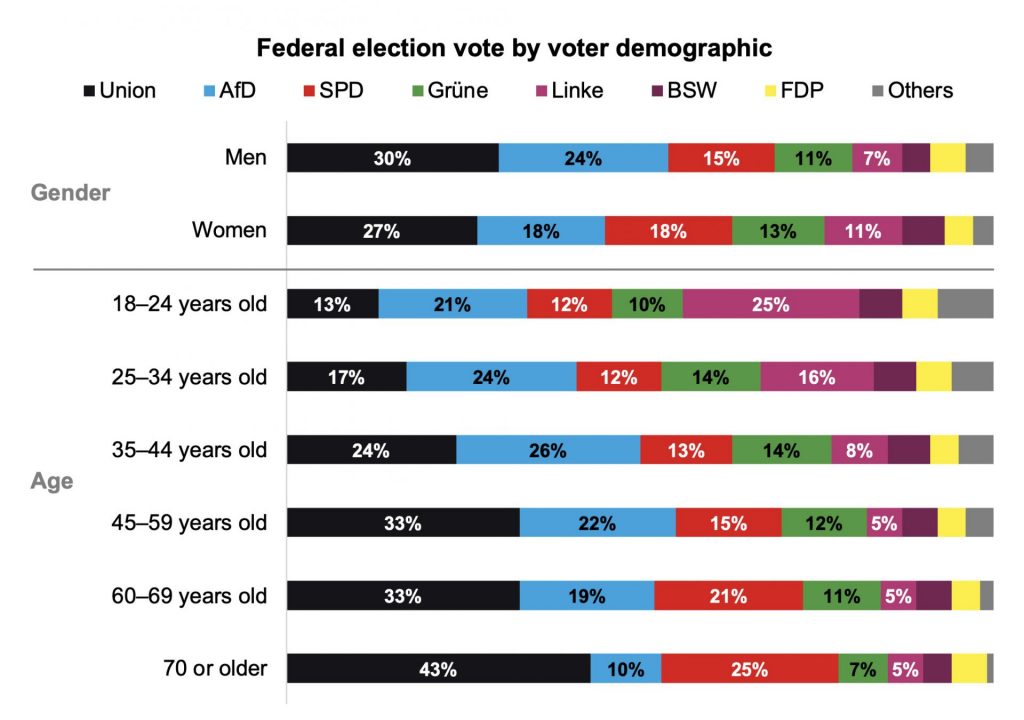

However, what is new is the total rejection of mainstream politics by a new class of workers, younger than the traditional working-class voters. They are angry and feel that government doesn’t work for people like them.

This is not a flank of the old right wing parties, but is a new and growing discontent that is born out of the failure of mainstream politics to connect in any relevant way with these younger voters and the struggles they face. As one told us: “They just don’t get it – it’s harder and harder for young people to get on – even if they apply themselves.”

This feeling goes hand in hand with the sense that the traditional class definitions that have defined political allegiance in the past are no longer meaningful. Instead, the much-loathed “mainstream” politicians are thought to be propping up a failed state for their own advantage.

As one woman put it: “The working class is dying. It’s the politicians who become rich. They’re the wheelers and dealers. We’re always the losers.”

Insecurity and pessimism dominated many voters’ mood on the eve of the German election. Worries about their financial security compounded worries about their personal safety, heightened by the ongoing war in Ukraine, illegal immigration and inflation. All this has turbocharged already-powerful feelings of unfairness and insecurity.

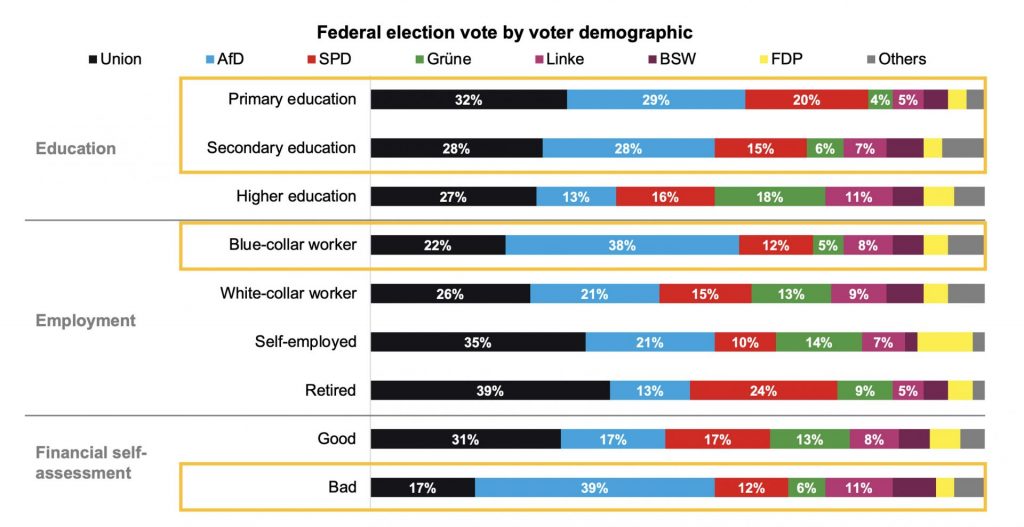

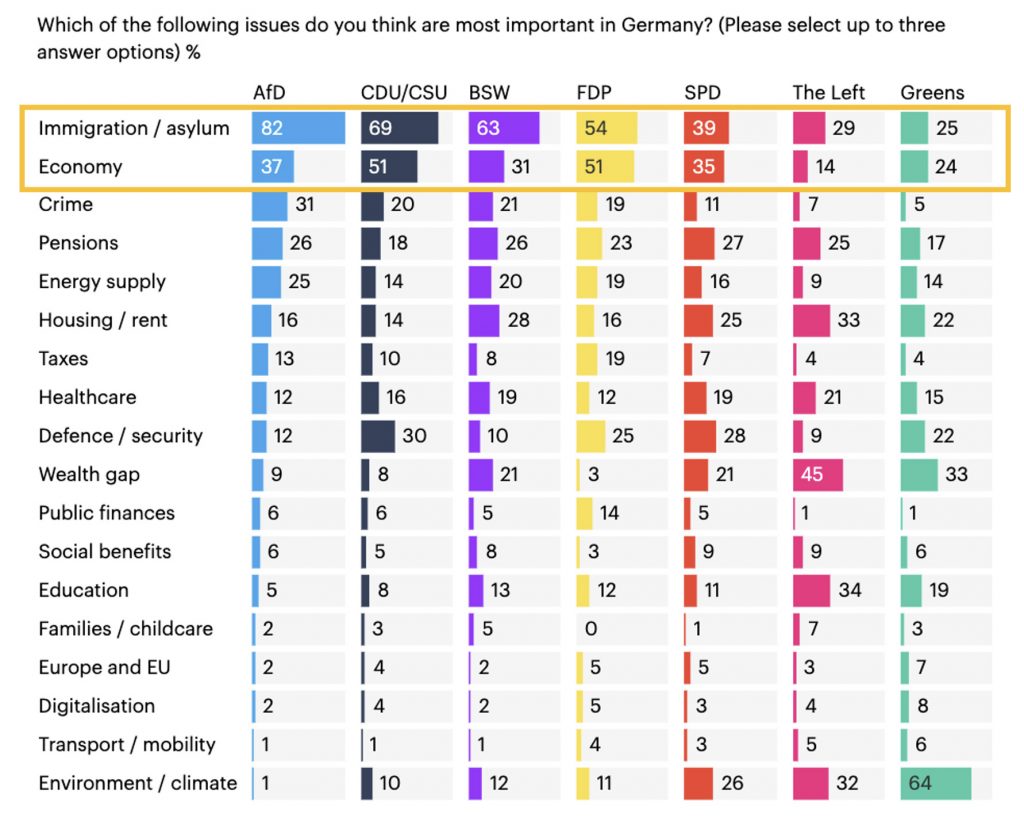

Immigration was the top issue for voters, in a country that has pioneered liberal immigration policies over the last decade, but at a cost to their way of life that many voters felt they could not continue to pay.

The topic dominated many of the focus groups. Observations like this were typical, from a woman who switched from SPD to AfD: “My son works hard but he can’t get an apartment. But the foreigners who come in here seem to get an apartment straight away. There is something very wrong with our country.” Immigration mattered most not just to AfD voters, but to supporters of every party except the Greens and the left.

Voters complained that they couldn’t get a hearing from the mainstream centrist parties for their concerns. One from east Germany told us: “The main parties only speak about immigration during the election campaign. They think little things like that are enough, it’s like giving little biscuits to doggies. But the AfD have spoken out for a long time.”

While Scholz did take decisive action to restrict border access, it was felt to be too little, too late. There were echoes here of Kamala Harris’s campaign message, which began to sound tougher on illegal immigration at the closing stages of the presidential campaign, but came long after most voters’ views had been cemented.

Centre-left parties have seemingly sounded too liberal and dismissive about illegal immigration for too long to rectify in the months before an election. Voters have been left feeling at best not listened to, at worst judged – all strongly reminiscent of the mood during the Brexit vote.

Most voters who switched felt bitterly let down by the German government and by Scholz, who was seen as passive and indecisive. Such is their disillusionment and passion for change that many talked openly about challenging the taboos in German society, like the historic block on working with far right parties in a coalition government.

Instead, they were drawn to a more dramatic change – a change born of a different politics that could break that “firewall”. Their disdain was not just for the outgoing incumbent – the CDU was also viewed with contempt.

Asked what drink reminded them of that party, one said, “a cup of cold coffee. Been around for a long time. Stale.” Another described them as “like Audi. A German institution but with a lot of recent problems that haven’t been fixed.” By contrast, the AfD was characterised as “an energy drink. Revitalising.”

So what does this mean for the centre-left in Germany, in the UK, and elsewhere?

It is clear that the forces powering voters’ discontent for many years are gaining pace, and sentiment is spreading, especially among the young. In the US, many Americans may feel wary about the changes Trump is bringing about, beyond the MAGA faithful. But one thing is clear: he stood for change and is now acting out that change, and change is what these voters want.

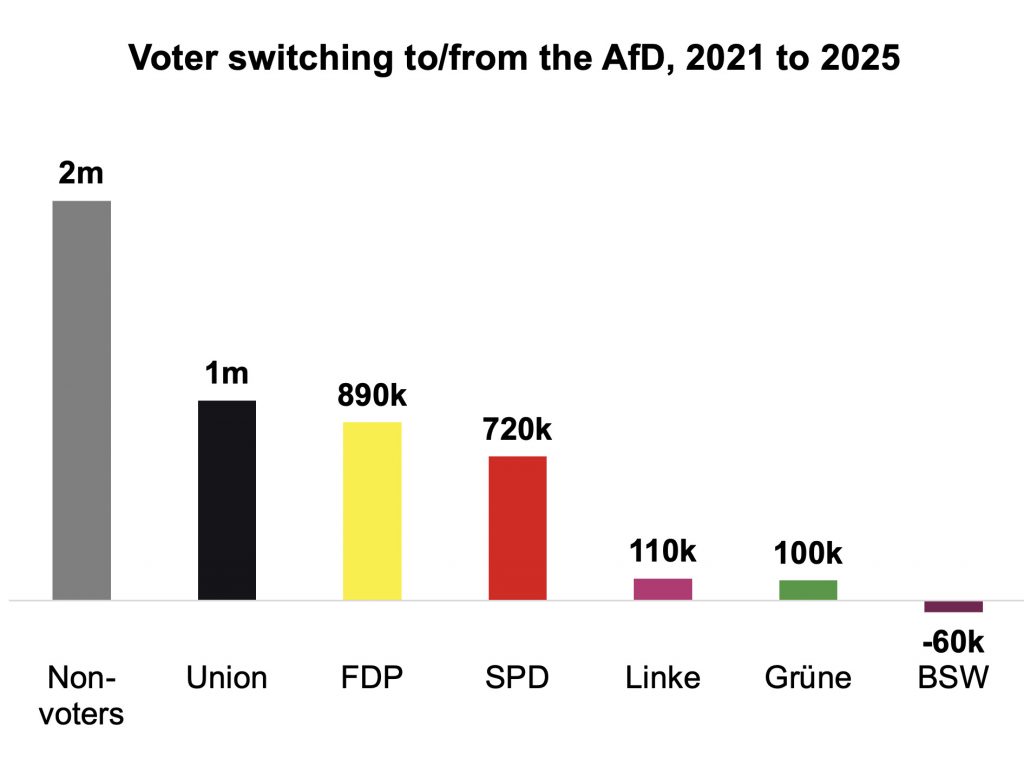

This phenomenon is no longer restricted to the former industrial heartlands of our countries, but is pervasive among struggling working people everywhere. They may not be diehard fans of the right, but the conditions remain ripe for cementing their support. Also noteworthy is that this group no longer sit out elections – the far right are attracting non-voters as well as voters from other parties.

It is clear that the absence of an attractive alternative proposition from the centre-left means that this rightward shift can spread further and faster. These voters must truly believe their efforts will be rewarded with an economic payoff and a government that works for them, including showing that immigration can be controlled.

Change needs to be radical, not incremental. However, this change cannot just be about policy solutions. Policy must symbolise intent.

But there has been a failure to make an emotional connection to convey that intent to disillusioned voters. This may well have mattered at least as much as any policy initiative.

The change voters need to see must be expressed by authentic politicians who manifestly “get them”. Trump’s success was, in part, in giving voice to the anger that many voters felt towards the status quo. Progressives need to learn the lesson and find new ways to have direct conversations with the voters they need to persuade.

As one SPD/AfD switcher told us: “The main parties now have four years to really understand voters like us. I still don’t think they get it. I hope they will by the next election.” It will be a lesson best learned now than in the aftermath of another defeat.

Baroness Deborah Mattinson was director of strategy to Keir Starmer 2021-24; Claire Ainsley was director of policy to Keir Starmer 2020-22, and is now director of the Progressive Policy Institute project on centre-left renewal.