Film critics might have ridiculed Adam Driver’s accent, castigated the graphic scenes of human carnage, and expressed amazement over how Penélope Cruz could maintain such a blood pressure-curdling degree of anger throughout the entire two hours of Michael Mann’s recent biopic, Ferrari. But what they couldn’t so easily spurn was the extraordinary story underpinning the film.

Their reviews may have been mixed, but racing fans cared little. And that’s because the movie culminates with the 1957 Mille Miglia, for so many reasons one of the most celebrated races of all time.

In the post-war years, the notoriously gruelling 11-hour race from Brescia to Rome and back on open public highways always threw up its share of the unexpected. From dawn to dusk, it took its toll on car and driver, spawning legends, apocryphal or otherwise. But 1957 proved to be both the event’s apogee and its curtain call. There would be unexpected glory, fairytale victory but, ultimately, tragedy of the most brutal kind. “Our deadly passion, our terrible joy,” to use the words of Enzo Ferrari.

And if Driver, consummately playing the eponymous racing manufacturer, couldn’t quite pull off an Italian accent, he gave enigmatic depth to the engineering colossus who became simply Il Commendatore, the titular head of the world’s most famous racing marque; moody and driven to the point of obsession, but – in 1957 – on the verge of bankruptcy. Win the most famous road race in the world, his anxious accountants begged, otherwise Ferrari would cease to exist.

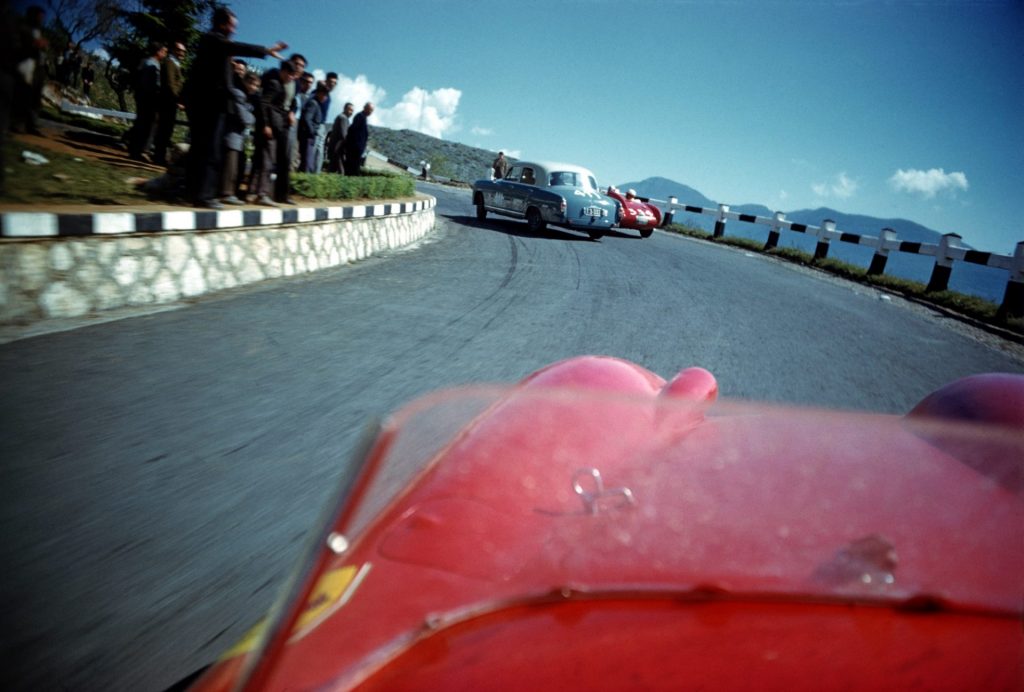

Mille Miglia, in Italian, means 1,000 miles, all raced uninterrupted by a single driver. Cars – almost 400 despatched at one-minute intervals – quickly became trains of vehicles as slower drivers held up faster rivals on narrow, twisting roads. With no spectator protection of any kind, the event always courted danger. Ferrari himself was tiring of the toll that racing took on his drivers, questioning the ethics of the sport he loved.

But danger also made races on public highways compelling. Cars passed within inches of fans lining the streets. Nowhere else could they get so close to the action.

It was also the era of the gentleman driver, racers who entered because they could afford to rather than because they necessarily had the ability. Ferrari’s team was a mix of such amateurs and professional drivers, among them renowned bon vivant, consort of actresses and models, the Marquess Alfonso de Portago, godson of Spanish king Alfonso XIII. Pilot, Grand National jockey and bobsleigh Olympian, he epitomised the playboy sporting all-rounder.

Up against him were four teammates, all Grand Prix drivers, including popular veteran Italian Piero Taruffi and pre-race favourite, Britain’s Peter Collins.

Taruffi, aged 50, was winding down his career. He had become more reluctant to race on open roads, realising he was not prepared to take the risks his younger rivals would. He promised his wife he would retire after the race which he had driven many times but never won. However, his experience offered one advantage – he knew the route well, so to save weight he eschewed taking a map-reading companion.

“At the start I felt marvellous,” he later said. “Free to race now I had taken the decision to retire.” Yet on arrival in Rome he learnt he was five minutes down on Collins. “But there is an old adage,” recalled Taruffi. “He who leads in Rome will not lead in Brescia.” He set about making the cliche a reality. “I flung the car from corner to corner,” he said, “trying to make up time. I tried so hard I damaged the transmission, and thought the game was up. But it was a spectacular way to lose.”

He crossed the finish line certain that his swansong had ended in another defeat, but his wife, struggling to reach him through hordes of fans, screamed: “You’ve won, you’ve won”. Collins had experienced similar transmission problems and his car had expired 125 miles from home.

“Briefly I was ecstatic,” he recalls. But then came news of de Portago. The Spaniard’s tyre had blown, killing him and his co-driver, but perhaps more tragically, 10 spectators, including five children.

A macabre scene in the movie depicts the tyre being sliced by a reflective road stud, but Taruffi suspected otherwise. “Sections of the route had granite kerbs. If you used them you could go faster round some corners, but the granite had sharp edges. A professional racer might have avoided these. My suspicion is the kerbs cut de Portago’s tyre.”

An against-the-odds victory was sickeningly tarnished. Road racing was banned on the Italian mainland and Ferrari faced prosecution on manslaughter charges.

His later acquittal – a guilty verdict would have finished the company – alongside Taruffi’s victory meant insolvency was avoided. But Enzo Ferrari remained eternally furious with both judiciary and press for portraying him as an uncaring tyrant who, concerned only with speed, built unsafe cars. He became ever more reclusive, henceforth refusing to watch his cars race in person.

And the day after the race he called Taruffi to his office. “Keep your promise to your wife,” he told him.