In Berlin, it is impossible to outrun the past. So some rush backwards to meet it.

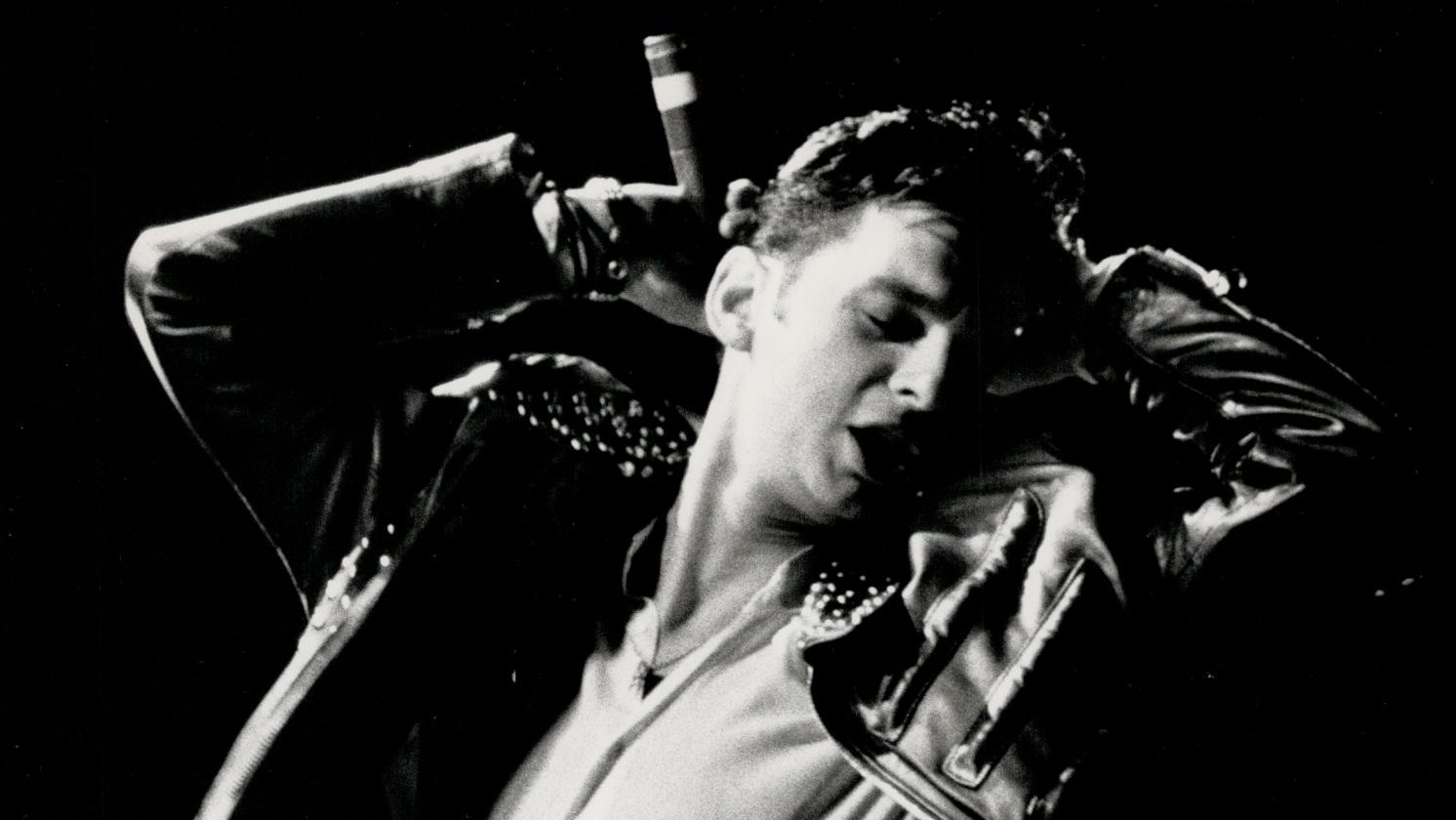

When the 18-year-old Helmut Neustädter fled Berlin on December 5, 1938, he left from Zoologischer Garten station – the “Bahnhof Zoo” familiar to David Bowie fans. As his train rolled towards Trieste and freedom, Neustädter would have caught a glimpse of the Landwehrkasino on Jebensstrasse, a club for military officers that became a popular theatre during the city’s Golden Twenties.

The Landwehrkasino now carries the name that Neustädter assumed after leaving Berlin. It is home to the Helmut Newton Foundation, showcasing the works and housing the archives of the great photographer and his wife, June Browne, who used the pseudonym Alice Springs. Late in his life, Newton picked the spot for a perfect homecoming, a closing of the circle, but died a few months before the foundation opened its doors in 2004.

The building is currently host to two remarkable exhibitions. One is of the work Newton made on his return to the city after the second world war (he never came back to live, preferring Paris, Monte Carlo and LA); the second collecting 17 other photographers’ images of the city, charting Berlin’s glory, its devastation and its rebirth.

Berlin, Berlin! is a chronicle that gathers Hein Gorny’s aerial views of the broken city, taken from a US army plane in the autumn of 1945, and Barbara Klemm’s jaw-dropping 1979 news photo of Soviet and East German leaders Leonid Brezhnev and Erich Honecker in a closed-eyed kiss, later to be immortalised in graffiti on the Wall. There are photographs of parties and protests, bars and bullet holes. There is a huge and almost overwhelming panorama of a ghostly street in Friedrichshain, assembled in the modern day from 32 photographs taken by Fritz Tiedemann in 1952.

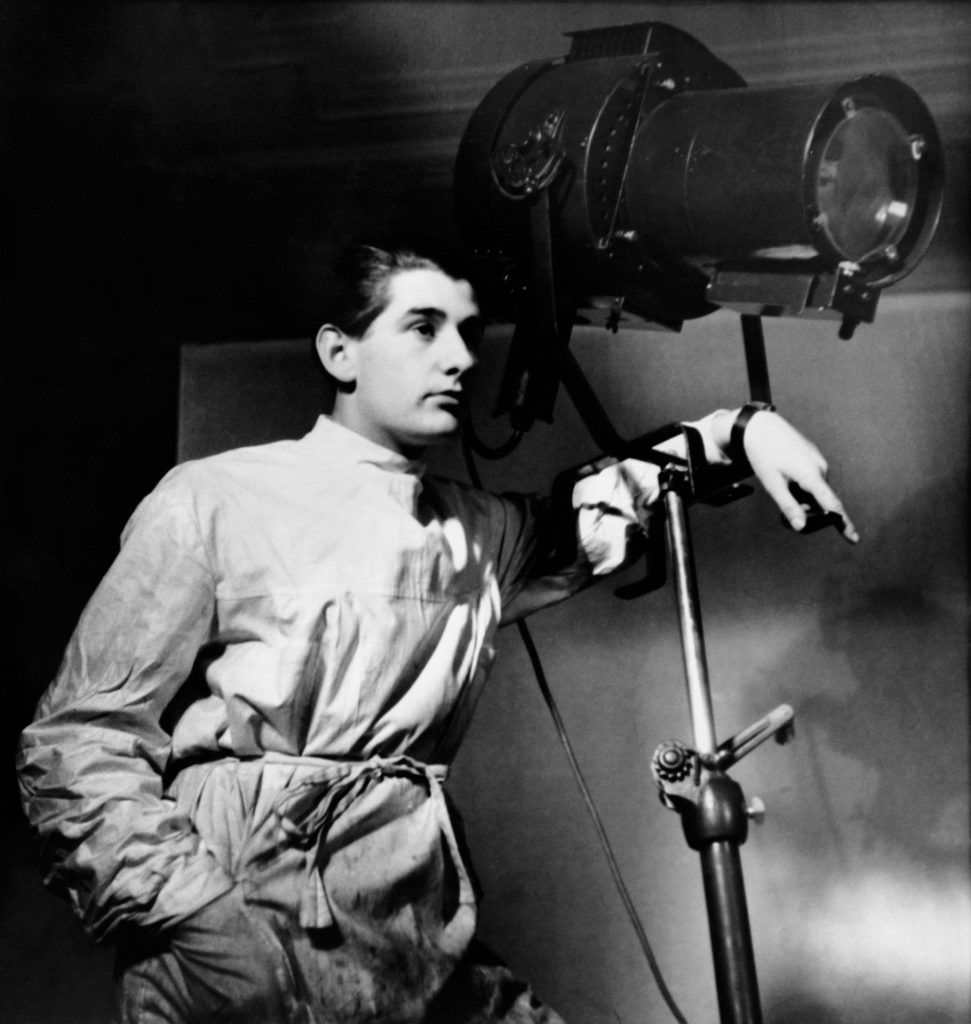

Berlin, Berlin! also includes wonderful images by Yva, the celebrated German-Jewish photographer for whom Newton worked as an assistant from the age of 16. She stayed in Berlin, had her studio and bank account confiscated by the Nazis and died, together with her husband, at the Majdanek concentration camp in 1944. Newton escaped and became a wealthy celebrity, following her path from striking fashion photography through dreamlike portraits and nudes.

Seen at such close proximity, her lasting influence on Newton’s use of light and form is apparent. Yet while Yva played with the surreal, her former apprentice delved into the dark emptiness of luxe life – the beautiful and blank-eyed, the decadent and doomed, that sinister something lurking in the corners of hotel lobbies, swimming pools and nightclubs.

Newton, who loved detective novels and films, was a great storyteller, but in his Berlin photographs there is only one story to be told. Even in his breezy commercial work from the early 1960s there are smiling models by the Brandenburg Gate, a site then still associated with Nazi iconography. Once his style has been established, things grow darker in every sense.

The foundation’s curator and director, art historian Matthias Harder, says, “you see a model by a construction site, but it’s not a construction site, it’s the Wall. And there’s another model, in a place where 50 people died. It’s very subtle. They are fashion pictures but they are not fashion pictures.”

Harder adds: “There’s melancholy in his pictures of Berlin, much more than his pictures from elsewhere. There’s a special atmosphere. It’s all a dream for him, but here the dream is different.”

Berlin, Berlin! is at the Helmut Newton Foundation, Jebensstrasse 2, 10623 Berlin-Charlottenburg, until February 16, 2025