Ava Gardner decides she really has to portray Billie Holiday in a film of Lady Day’s life. Let that sink in for a moment.

It’s the mid-1950s, and madness reigns. Gene Lerner, Gardner’s friend and representative in Europe, is trying to reason with her, without specifically denying her, er… idiosyncratic vision.

“A white woman doing Billie… it’s tough, Ava. But I really think you can do it.”

Lerner’s main stumbling block, of course, is the fact that Gardner is white and Holiday wasn’t. And Holiday’s fans might struggle with this.

“How are we going to know if the blacks will buy me?” asks Gardner. “Do we just go out and take a poll?” Lerner ponders this and then suddenly claps his hands in a moment of inspiration. “I know! We ask Jimmy Baldwin!”

Which is exactly what they do. They track the great author James Baldwin down to some flophouse in Istanbul and ask his opinion on something that probably wouldn’t have crossed his mind if he’d lived a thousand lifetimes. Should Ava Gardner play jazz icon Billie Holiday?

To his credit, Baldwin, who was not commonly known for reticence and tact in the face of the preposterous, reasons: “It is widely rumoured – and this may sound like a joke, but it isn’t – that Ava Gardner is white… in this particular case, I don’t quite see how we could hope to get around this problem.”

Insanity. Absolute insanity. But a fairly typical moment in the momentous Hollywood on the Tiber.

Don’t get me wrong. I love a stolid, studious account of cinema history. Something like The American Cinema by Andrew Sarris or Otto Friedrich’s masterly City of Nets. But there is something else I love even more: juice, trash, unsubstantiated slander and sleaze. Filth such as Kenneth Anger’s Hollywood Babylon (teeming with completely made-up tales, but then again, who cares?) or Barbara Payton’s incredible anti-memoir I Am Not Ashamed, perhaps the most depressing and degrading Hollywood tome ever released.

Hollywood on the Tiber is not quite on a par with those paragons of the perverse, but it is an affectionate, pacey and, most importantly, thoroughly indiscreet romp through the Roman film industry of the 1950s and 60s. Written in the 1970s by American-born, Italian-based agents Hank Kaufman and Gene Lerner, it recounts their adventures during the Dolce Vita years, hosting debauched, celebrity-filled soirees they dubbed Cocktailus Romanus.

It was only ever published in Italy during the early 1980s. The pair attempted to release an English-language edition, but for unknown reasons (possibly legal) only the Italian version emerged.

Then, legendary producer Sandy Lieberson (who worked for Kaufman and Lerner in the 1960s and writes the book’s introduction) revealed to publisher Paul Cronin that he’d just unearthed the pair’s original English-language manuscript. Luckily Cronin, through his Sticking Place Books imprint, happens to publish lost and obscure books on cinema. And so Hollywood on the Tiber was reborn.

The authors are a fascinating couple. Both business and romantic partners, Kaufman hailed from advertising, while Lerner was an aspiring playwright.

In the early 1950s, they moved to Europe, settled in Rome and, despite possessing no obvious talent for such things themselves, opened a talent agency in the city. Their timing was immaculate.

1953 was a blockbuster year in cinema. And two cinematic events in particular would help to establish an expressway between Hollywood and the Eternal City.

The Robe, the world’s first CinemaScope release, was the year’s top-grossing film. A sword-and-sandals epic about Christ’s crucifixion, the film’s star, Richard Burton, called it “dull as ditch water” that made him want to “throw up”. Despite that, it made millions.

Less successful, but perhaps more culturally significant, was Roman Holiday, which launched the career of Audrey Hepburn and shot Vespa sales through the roof. Suddenly Hollywood wanted two things in large numbers; big-budget extravaganzas featuring burly, oiled men throwing tridents at each other (Cleopatra, Ben Hur, Quo Vadis) and/or sweet, romantic stories of dewy-eyed ingenues abroad, drifting through a slightly Disneyfied version of Europe while being pursued by worryingly older men (Three Coins in the Fountain, Paris When it Sizzles, The Barefoot Contessa).

Add into that mix a bevy of blacklisted writers, flushed out of the States thanks to Senator Joe McCarthy’s communist-baiting Senate hearings, who washed up in Europe and were desperate to work; plus stars trying to escape the constant attentions of the LA scandal rags (and running straight into the arms of the paparazzi); and the fact that many of the big studios had money tied up in Europe that had to be spent in the countries it had been generated in.

All this resulted in a second cinematic front opening up on the continent, in the city most amenable to Hollywood’s advances: Rome. They had studios, sunshine, and crew willing to work for a fraction of the cost back home. Soon homegrown Italian actors, American superstars and European talent were converging on the city, desperate to hoover up the parts and cash the studios were throwing around. And these people needed representation. Step forward Kaufman and Lerner.

The pair were intimately entwined with the lives of their clients in a way I’m happy to describe as “unhealthy”. Soon after opening their offices, they found themselves fielding calls in the middle of the night from an enraged Anna Magnani desperate to vent about love rival Ingrid Bergman.

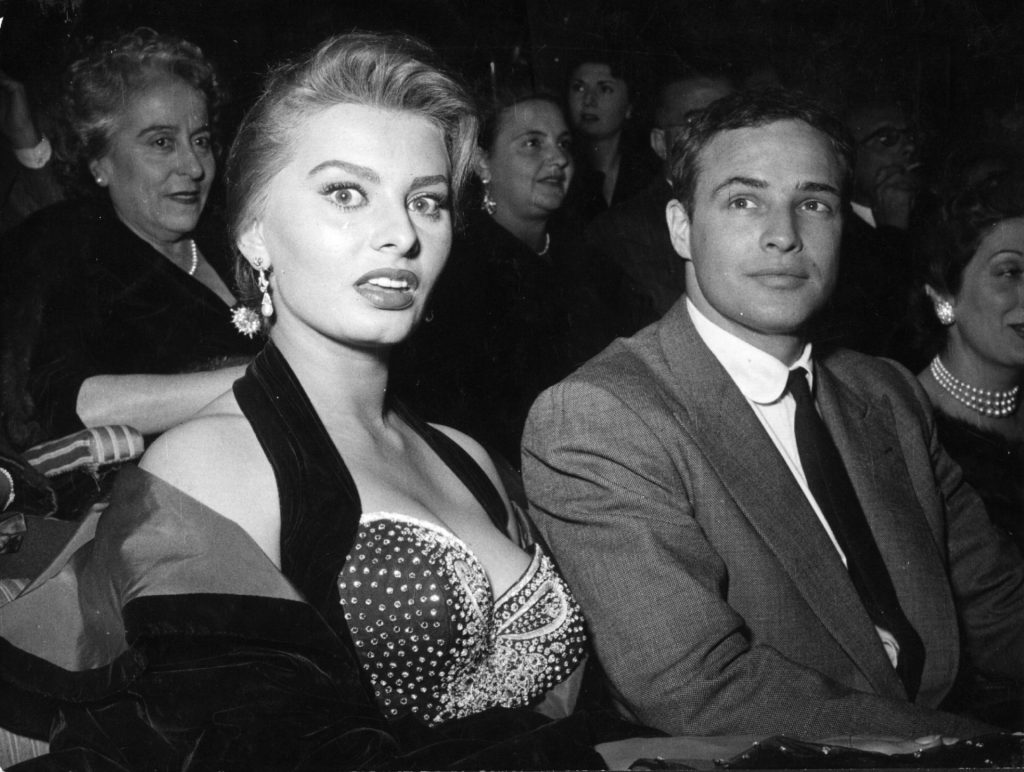

Later, they are soothing a hysterical Marlon Brando, who had witnessed a dubbed version of On the Waterfront at the film’s Italian premiere (Brando is distracted by being seated next to Sophia Loren and particularly her bosom. The book quotes him as saying: “That dame’s great. Great. Both of her. I’ve never ever seen such a double feature.” Class act, that Brando).

Then there’s the undercover operation to snaffle Simone Signoret out of Paris before the premiere of the film Let’s Make Love, starring Yves Montand (her husband) and Marilyn Monroe (her husband’s lover, allegedly), which was generating a media frenzy. Or Anita Ekberg sobbing in a rural Italian hotel after locals threw rocks at her silver Ferrari due to her ribald reputation, and demanding Kaufman and Lerner do something about it.

And then there’s Gardner. Oh Ava Gardner. She’s all over this book like a beautiful rash.

Her life is absurdly chaotic, dramatic and baffling, even when she wasn’t trying to portray Billie Holiday. One minute she’s popping up in Oxford, to be serenaded poetically by a smitten Robert Graves (no, that one wasn’t on my bingo card either). Or else she’s having clumps of her hair pulled out by a deranged George C Scott at the Savoy, while he also attempts to strangle Lerner with a bath towel. Or being convinced to resume work on Dino De Laurentiis’s epic The Bible by having a short story by IL Peretz read to her.

And then there’s so much more. Gina Lollobrigida and the astronaut. Shelley Winters and the spaghetti. Esther Williams doing something unspeakable in the back of a limousine. And through it all Kaufman and Lerner stoically pick up the pieces and their 10% commission even though, due to a Mussolini-era prostitution law, agents were illegal in Italy at the time.

If the book has one failing, it’s that we never learn enough about Kaufman and Lerner. Their private life is only hinted at. I would have loved to have known how their clients responded to a gay couple managing their affairs, or even if they realised this was happening (Magnani appears to have a Queen Victoria level of understanding concerning homosexual matters).

There’s also a level of remove due to the third-person approach of the book. Kaufman and Lerner write about two characters called “Hank and Gene”, often in novelistic, even pulpy ways. (For instance, regarding De Laurentiis they write: “A shrewdness coursed through his brain as saliva filled the throat of a dog undergoing his Pavlov.”) It’s over the top in the way Robert Evans’s equally eccentric The Kid Stays in the Picture is over the top. Delightfully so in small doses.

But all this Chandler-esque zing and zap just adds to the demented exuberance of the time documented in the book.

Fellini’s masterpiece La Dolce Vita (inspired by the real-life antics of Ekberg), its manic energy, its unstable glamour, its visceral, dreamlike quality, dangles auspiciously over the whole book. Their account of convincing Ekberg to star in the film is astonishing. Lerner basically forged her signature after she tried to back out. La Dolce Vita was a global phenomenon when it was released in 1960, just as Kaufman and Lerner were at the height of their powers. Ekberg, featured on the poster, instantly became an icon.

Suddenly everyone, including Charlie Chaplin, David Lean, Franco Zeffirelli and scores of others wanted to do business with them. A decade later, after many more hysterical actor outbursts, endless parties and dodgy Italian producers threatening their wellbeing, they were spent. They returned to the US and produced a highly successful Broadway show about Kurt Weill. Lerner died in 2004, Kaufman in 2012.

But we can thank the cinema gods that Kaufman and Lerner wrote everything down, and now their forgotten reminiscences can be marvelled at by all. It provides an insider account of an alternative Golden Age of Hollywood, told at breakneck speed with jaw-dropping stories scattered throughout.

As Lerner writes to Kaufman in the book’s epilogue: “We were the hosts of a grand party, a very special, very joyful, Cocktailus Romanus.

“The biggest and most successful of them all.”

Hollywood on the Tiber is out now, published by Sticking Place Books. Dale Shaw is a television and radio writer, journalist, fiction writer, performer and musician