It is hard to imagine the 007 film franchise being anything other than a cultural behemoth, but in the mid-1970s there were doubts regarding the entire future of the series. The Man with the Golden Gun (1974) had not performed as well as expected at the box office and a series of problems faced its successor, The Spy Who Loved Me.

While producer Albert “Cubby” Broccoli could use the title of Ian Fleming’s novel, he did not have rights to the book itself, meaning a new script was required. A dozen screenwriters, from John Landis to Anthony Burgess, were called in and when the final version was green lit it was promptly slapped with two plagiarism lawsuits.

Among other rights complications, Broccoli did not have permission to include Bond’s nemesis Ernst Stavro Blofeld in the new production. So the writers came up with Karl Stromberg, a megalomaniacal Swedish marine biologist and shipping-line owner living in an undersea base off Sardinia from where he planned to destroy humanity in order to live in peace in his marine world.

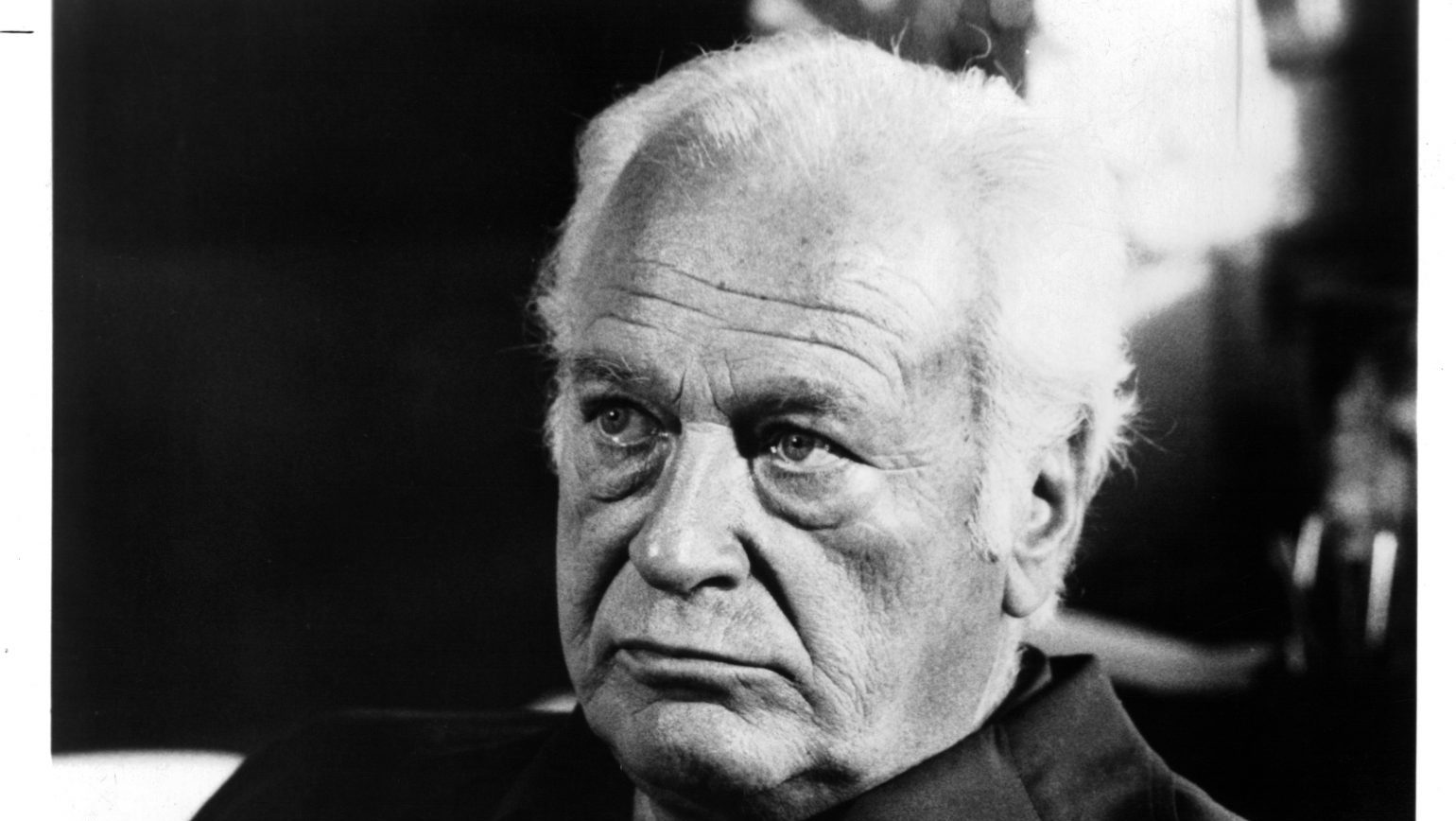

The role of Stromberg went to Curd (billed as Curt) Jürgens, a silver-haired, charismatic German actor whose film career would span more than 150 productions in Europe and the USA. A new character replacing an established key figure in the series presented a daunting challenge to any actor, but for the man who had been effectively the face of postwar German cultural rehabilitation, this challenge was a minor one.

Indeed, Jürgens relished the role. Having made his name portraying characters more nuanced than the ruthless Nazis who had dominated the screen, playing instead decent men trying to do the right thing in impossible circumstances in a world gone mad, the opportunity to play an unreconstructed bad guy was too good to miss.

“Villains are more interesting than heroes,” he said. “Nobody wants to play Faust but everyone wants to be Mephisto.”

He might have trailed in the publicity behind Roger Moore as Bond, Barbara Bach as KGB agent Anya Amasova and Richard Kiel as ruthless, metal-mouthed henchman Jaws, but Jürgens’ assured charismatic malevolence was key in making The Spy Who Loved Me a box office success, securing the franchise and ensuring his own cinematic legacy would be more than just a conflicted Nazi with a heart.

The Spy Who Loved Me was also a neat milestone in Jürgens’ career, coming 20 years after his breakthrough English language role as a U-boat commander in 1957’s The Enemy Below. Sick of fascism and wearied by the futility of war, Captain von Stolberg finds his damaged vessel being pursued around the north Atlantic by Robert Mitchum’s US destroyer, a grubby hunt to the death transformed by its leads into something approaching chivalrous knightly combat.

“It is due to Jürgens’ projection of character that we are able to accept the concept of a good man who wears the swastika,” said the Hollywood Reporter, with Jürgens himself also aware of the role’s significance.

“It was the first film after the war in which a German soldier was not portrayed as a freak,” he said. “I was grateful for the part; it gave the world a new perspective on Germans. It was a tricky time when I came to America as the first German actor after the war because there was still a lot of resentment in Hollywood.”

Jürgens made a convincing military officer despite not having served himself. His Nordic looks and bearing – 6’4” tall with blond hair and blue eyes – alongside his talent meant the Vienna-based actor was excused conscription in favour of a place on the stage and in front of the camera.

“I am probably praised primarily because the new blond German matches what the Viennese in their enthusiasm for the Anschluss want to see,” he said of his popularity during the Third Reich. Jürgens was far from an idealised loyal Aryan, however. Nazism appalled him and he was not averse to showing it.

One night in September 1944 he was in a Viennese bar popular with military officers, one where “actors were accepted and we could get what was left over from the officers’ beautiful dinners”.

An officer sitting nearby had, Jürgens noticed, enormous ears, which he sniggered at and mimicked to his female companion despite being close enough for the man to notice. “The man,” he recalled, “was Skorzeny.”

Otto Skorzeny was a ruthless SS officer who had a few months earlier led the raid that sprung Benito Mussolini from captivity in Italy. Skorzeny’s companion had also noticed Jürgens’ antics. He was Robert Kaltenbrunner, brother of Ernst Kaltenbrunner, the head of the Gestapo.

“We got up to leave and Kaltenbrunner stopped me and said, why are you not a soldier?” recalled Jürgens. “I explained that I was one of the actors in the Burg Theater exempted by Goebbels to entertain the people.”

A heated discussion ensued that escalated into shoving and then to a full-on fist fight, one in which Jürgens held his own impressively despite being outnumbered. Arrested and sent to a labour camp as a “political undesirable”, Jürgens escaped after a few weeks and laid low until the end of the war.

Such stories only added to the aura of a man Brigitte Bardot described as having more sex appeal than any other and who Ingrid Bergman said possessed more charm in his little finger than most men had in their whole body.

The Kaltenbrunner incident seemed to convince Jürgens that life was something precious, something from which to wring every ounce of joy possible. A life his cinema earnings permitted.

“I only act for money,” he said. “You can tell that by some of the rubbish I’ve done. It is amazing to me that producers continue to pay me so much for the films I do.”

Five times married, he lived between his six luxury homes – “my father lost all his money in the 1929 stock market crash and I was brought up never to trust shares. My mother had a French peasant’s mentality and she always said ‘buy land’, so I did” – where he threw legendary parties. On the set of The Spy Who Loved Me, Jürgens’ descriptions of his lifestyle in Gstaad convinced Roger Moore to promptly move there himself.

Jürgens listed his priorities as “comfort, women, whisky, marriage and work” and compromised on none of them. When he lay on his deathbed aged 66, even his heart surgeon had admiration in his voice when he said: “He is paying for a lifetime of sins against all the rules of good health”.