In 1943, the year of her death, the philosopher and activist Simone Weil wrote a powerful essay demanding the abolition of all political parties.

Such social organisations, she wrote, were no more than machines to stifle free thought and “to generate collective passions”. So harmful were political parties, indeed, that “[i]f one were to entrust the organisation of public life to the devil, he could not invent a more clever device”.

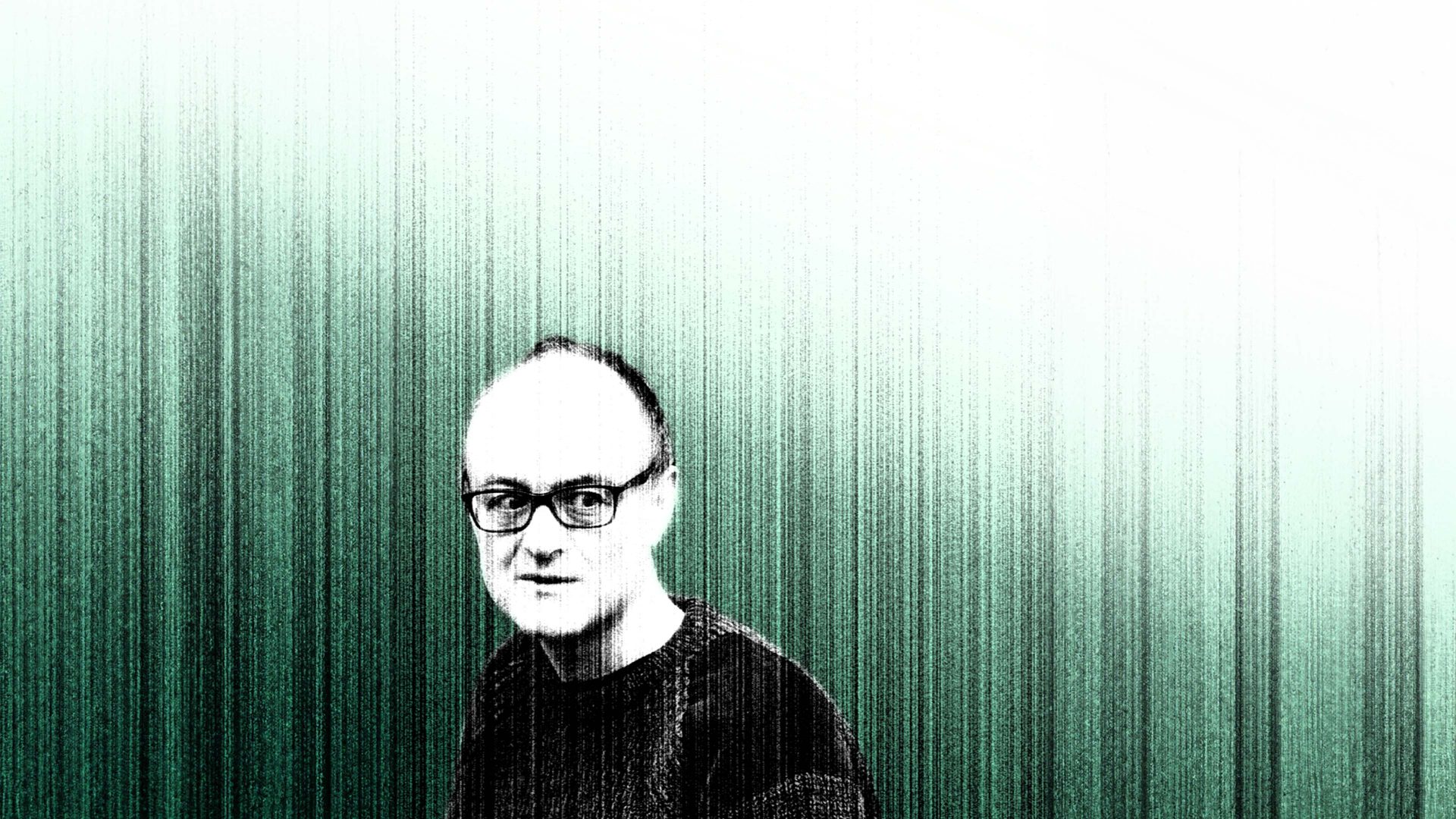

Weil’s essay, unpublished until 1950, has remained an influential text. Still: nobody has come up with a better way of organising collaborative activity in a democracy. And now Dominic Cummings, the force behind Vote Leave’s referendum victory in 2016 and Boris Johnson’s general election triumph three years later, wants one of his own: its working name is the Startup Party, though I suspect that will change.

In an interview with the i newspaper last week, Cummings explained his rationale. “The only point of doing it is to do something which is completely different from the other parties,” he said. “The Tories now obviously represent nothing except a continuation of the shitshow.”

As he himself concedes, the odds are always stacked against new parties, not least because of the first past the post system, which stops emerging groups getting a toe hold on the ladder. It is also not yet clear what, precisely, the Startup Party would credibly offer that was new and galvanising to the UK’s jaded electorate.

In a Substack post in August, Cummings set out some of the first principles that would underpin the proposed new group: principally a “focus on the customers not the competition — i.e the voters, not the other parties. This is a superpower that the old parties, optimised for maintaining social relationships in London, are unable to copy.”

The Startup Party, he wrote, would repeal the Human Rights Act and “end the jurisdiction of the Strasbourg Court”. It would eliminate “the ways in which richer people and powerful incumbents have unfair advantages in tax, law etc”. It would find “new ways to deliver services people want”.

It would “cut illegal immigration to a tiny and irrelevant problem”. It would not “accept a penny of taxpayers’ money to fund the party”. It would ensure that MPs’ salaries were “linked directly to the rise/fall of median incomes”. Much of this is familiar to those of us who have followed the founder’s techno-populist evolution over the years.

To be fair to Cummings, he has no shortage of ideas (that was never the problem). And he is right that “the Tory brand is horrific”, in an even worse state than the vast majority of Conservatives have yet realised. After the election, there will indeed be a case for rebooting rightwing politics entirely.

But, as Cummings himself acknowledges, quoting his hero, the US air force colonel, John Boyd: “People, ideas, machines – in that order!” The hardest task facing anyone who would construct a party from scratch – a political terraformer, so to speak – is to identify and recruit fellow builders: strategists, candidates, leaders. Cummings is undoubtedly an astute spotter of talent and commands greater loyalty and affection among his subordinates than his public image as the potty-mouthed lone wolf would suggest.

All the same: would you want to be the first leader of the Startup Party? Cummings promises that “if I can do this and it grows then I will step back”. That sounds exactly the sort of thing that Big Brother would have said in the early days: “Me? In charge? On the posters? You’re having a laugh, aren’t you? No, no, I’ll stick to slogans and torture, thanks very much!”

Every time Cummings appears before a public committee – most recently, the Covid-19 Inquiry in October – and we hear again of his brutal methods, compulsive scheming and bullying tactics, the easier it is to dismiss him as a wrecker who ended the UK’s relationship with the EU and, in his feuding with Johnson, turned Downing Street into a crucible of mayhem. And all that is true.

Nonetheless: it is a mistake not to study what he got right. Yes, he has left a terrible stain on British public life; but he was able to do so because he understood new realities that completely eluded pro-EU and progressive politicians.

In particular, he grasped that digital technology had utterly transformed the political landscape and electoral communication. Eight years after the referendum, the left-of-centre has just about got its head round social media. Meanwhile, the populist right is busily exploring the possibilities of AI as a campaign tool and the malign potential of deep-fake media.

Cummings also understands the radically changed social setting in which institutions are being replaced by networks; in which politics, in the words of the Oxford academic Philip N Howard, is no longer to be understood as a series of interactions between antiquated public bodies but has become “a system of relationships between and among people and devices”.

In this new world of instability, unpredictability and volatility, what matters is not institutional tradition but limitless agility. Cummings initially hoped that the Vote Leave caucus could take over and reinvent the Conservative Party. Now he envisages a separate organisation entirely.

He is less interested in the delivery system – old, new, who cares? – than the viability of the project. Why not set up his own shop?

Nigel Farage, though no friend of Cummings, shares this insight and understands that parties come and go: Ukip, the Brexit Party, Reform UK… maybe Tory leader next? His friend Donald Trump, after all, has essentially abolished the Republican Party, founded 170 years ago in Ripon, Wisconsin, and replaced it with the Maga movement. The coalition that has propelled Javier Milei to the Argentinian presidency – La Libertad Avanza – did not exist three years ago.

The new Cummings product has not yet been released even for beta testing. Most such products fail. What matters is that its success is even conceivable. Therein lies the true lesson for the rest of us.