When the UK’s Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority was established in 1991 in the wake of the advent of in vitro fertilisation (IVF), it was intended to regulate the use of human embryos both for reproductive purposes and in the scientific research made possible by the excess embryos generated for IVF. It was the first body of its kind in the world, and is now widely admired as a model of how to combine clear, strong regulation with a permissive research framework for embryology.

But no one could have imagined back then the issues – scientific, ethical and even philosophical – the HFEA would be required to navigate. For example, in 2015 it approved mitochondrial replacement therapy, in which the cellular components called mitochondria are substituted in a fertilised egg during IVF by those of a third-party donor to avoid some nasty inherited diseases. (Children have now been born using the procedure.) The HFEA is also weighing up the risks and benefits of editing the genomes of embryos to address genetic conditions. This is forbidden internationally if it would extend to the sex cells and thus be inherited by offspring.

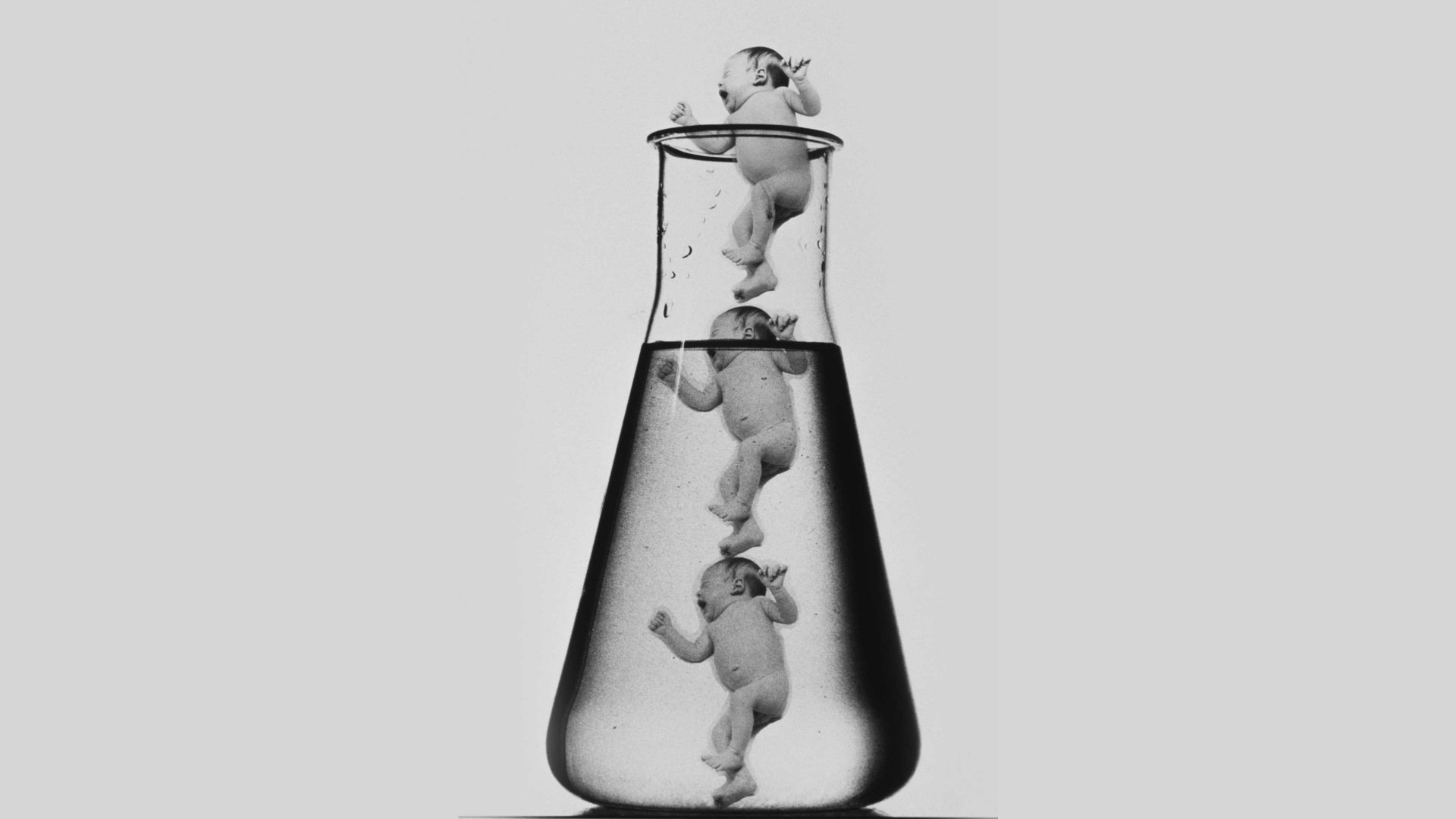

Over the past year or so the HFEA has been grappling with an even more futuristic-sounding scenario: the potential creation of human embryos from stem cells without the involvement of gametes at all. It’s been known for several years that embryonic stem cells – which can make any tissue type in the body – can organise themselves into clusters that look and develop much like a normal embryo does. In a dish, these “embryo models” can’t become a foetus. But when embellished with cell types that support a normal embryo, such as those that make a placenta, mouse embryo models have been shown to develop a primitive beating heart and the first vestiges of a brain, limbs, and other organs. If they were to be implanted early enough in the womb, no one knows how far they might get.

These structures could be used to study aspects of human embryology that aren’t accessible to research on IVF embryos (which cannot be studied beyond 14 days after fertilisation). They might, for example, help to answer questions about why some pregnancies terminate early on, or to explore the origins of developmental defects. Last summer researchers unveiled human embryo models comparable to real embryos after about 14 days of growth.

The term “embryo models” is preferred over “synthetic embryos” to emphasise that these entities are not really embryos. Pretty much all researchers agree that they should not be implanted in a human uterus for any reason. But beyond that, it is not at all obvious how to think about them. There is no one-size-fits-all ethical framework. Some models only crudely approximate real embryos; that can still make them useful for research, but renders them more like lab-grown cells or tissues than nascent organisms. But for some purposes, the more closely embryo models resemble real embryos, the more meaningful the inferences derived from them. Then, however, the distinction between embryo models and actual embryos becomes blurred.

So should embryo models be subject to the same regulations as embryos? Or do they need some bespoke framework? Must each case be decided according to the precise nature of the model concerned? Does the definition of an embryo itself need changing?

Such questions have been considered by Cambridge Reproduction, an organisation based at Cambridge University, in collaboration with the London-based charity Progress Educational Trust. In early July the collaboration, having conducted extensive public consultation, issued a set of guidelines for governance of research on human embryo models, which included establishing an oversight committee to review individual research proposals. Although voluntary, the guidelines are the first of their kind in the world (the International Society for Stem Cell Research has a working group on this issue) and will surely feed into the HFEA’s deliberations.

At root the problem is that there is no off-the-shelf moral framework one can use in cases like this, where science and technology create unprecedented possibilities and unsettle conventional categories. But the Cambridge Reproduction consultations showed how important it is to explain to the public what the potential benefits of such research are, and illustrated that people are very able to deliberate complex ethical issues like this when adequately informed. Here, broad and inclusive dialogue is vastly preferable to relying on obsolete moral formulas or instinctive prejudices.