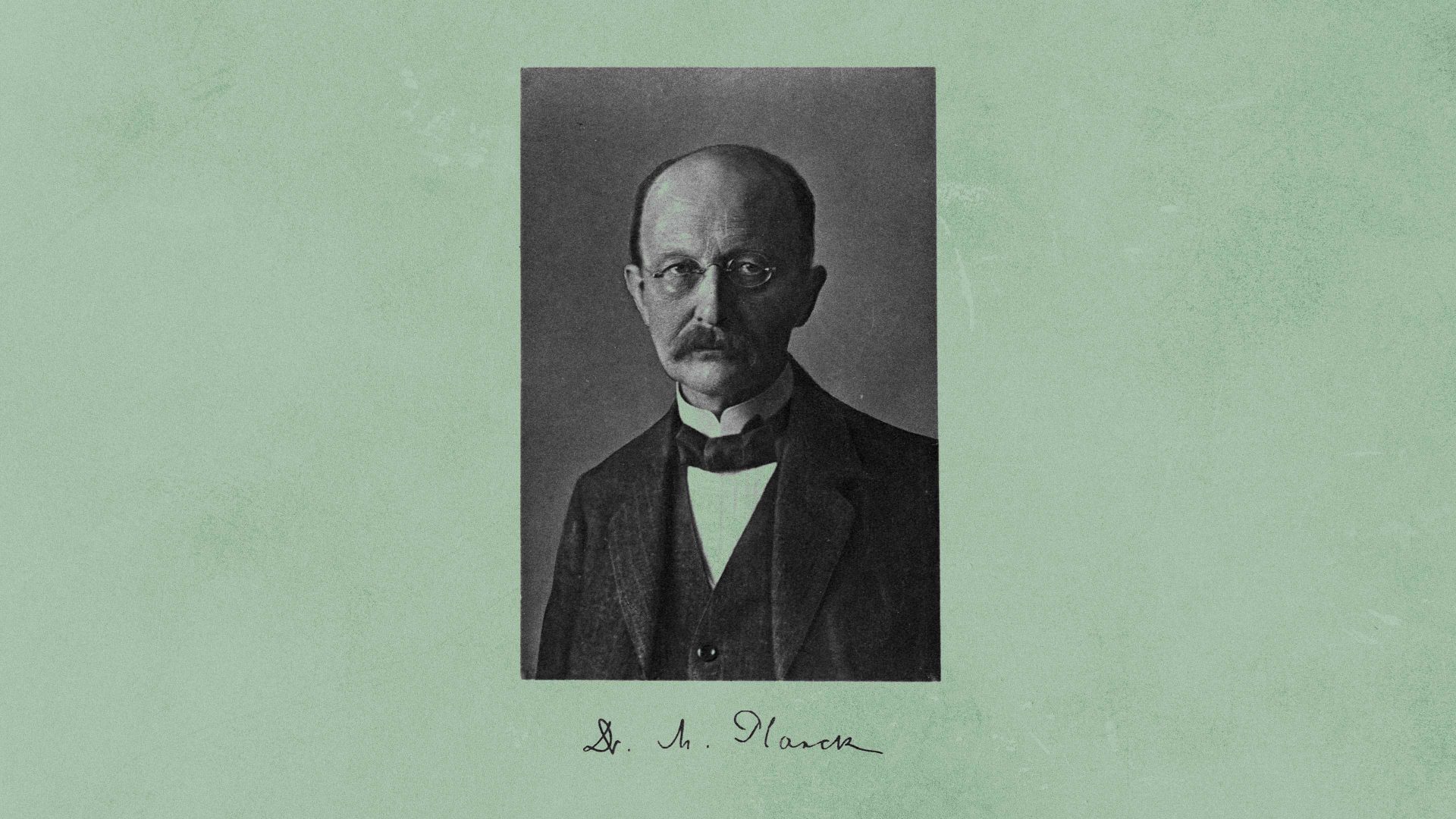

Next year has been officially designated the centenary of quantum mechanics, the theory that transformed our understanding of the microscopic world of atoms and their component particles. But while the crucial developments in quantum theory indeed happened in 1925-6, it all stemmed from a revolutionary idea put forward in 1900 by the German scientist Max Planck, who worked from 1889 to 1926 at the University of Berlin.

Planck was no one’s idea of a revolutionary, and indeed was initially reluctant to embrace the implications of his remarkable idea. He was trying to understand a question preoccupying physicists at the end of the 19th century: how warm objects radiate heat. Planck suggested that the particles that make up the object vibrate when warmed, and the vibrations induce light waves – first at infrared frequencies, but also including higher-frequency visible light as the object gets hot enough to glow visibly. To make his theory of this process fit the experimental results, Planck suggested that the vibrations can’t have just any old frequency, but are restricted to particular values: in the jargon, they are quantised, the vibrations jumping abruptly from one permitted frequency to another.

To Planck this was merely a mathematical trick (he called it a “fortunate guess”) to get his equations to work. But five years later, Albert Einstein proposed that we should take these “quanta” literally. He argued that light is itself quantised, its energy carried in little packets later called photons. In other words, at the microscopic scale energy, light and matter are all grainy and quantised, in contrast to our experience in the everyday world where, say, the speed (and thus the energy) of a spinning bicycle wheel seems to change smoothly.

Planck was persuaded only slowly that Einstein was right – he wanted the quantum hypothesis to be introduced into physics “as conservatively as possible”. But once convinced, he became a leading champion of the quantum theory, for their formative roles in which both Planck and Einstein won Nobel prizes. Planck was seen by many German scientists as their senior statesman: from 1930 to 1936 he was president of the umbrella scientific organisation called the Kaiser Wilhelm Society (KWS, renamed in 1948 the Max Planck Society, which today operates institutes all over Germany). For this reason, they looked to Planck for leadership when the Nazis came to power in 1933.

Thus began Planck’s tragic trajectory. As a product of bourgeois and nationalistic Prussian culture, he was instinctively conservative and instilled with a sense of duty to the state. That the state could become corrupt and morally repugnant was not a possibility he could have imagined, and Planck failed to find the moral backbone to confront Nazi depravity. He deplored the attacks on Einstein’s “Jewish physics” from some of his virulently antisemitic colleagues, but nonetheless he felt he could only “fall silent and leave” when faced with Hitler’s rabid “frenzy” in a 1933 meeting of the two men. As president of the Prussian Academy of Sciences, Planck capitulated to demands that he write a letter of condemnation to Einstein after his friend spoke out from America about Hitler’s regime.

In this regard Planck typified the response of many of his colleagues. Repelled by the fascists and their antisemitic and eventually genocidal measures, he nonetheless lacked the personal resources to muster any effective resistance. As a state employee in his role as university professor, he took the conventional view that he should stay professionally aloof from politics – to be “political” (as Einstein was) implied something akin to a lack of patriotism. Which was naturally just how the Nazis liked it. Because he dragged his feet about implementing the required expulsions of Jews from the KWS, he was condemned as useless and “ignorant about race” by scientists with Nazi sympathies, but his was largely a policy of appeasement. Planck’s son, Erwin, was more forthright, being active in the plot to assassinate Hitler – for which he was executed in 1944, despite his father’s appeals. Having lost his first son in the first world war, this final bereavement left Planck a broken man when he died in 1947. In the evaluation of his biographer John Heilbron, he was a decent and gentle man tragically betrayed by his own beliefs.

The moral for today could hardly be more clear or urgent: in times of state corruption and political interference, scientists remain “apolitical” at their peril. It would be unfair to judge Planck too harshly for his failings, but the important lesson is surely that scientists need to find collective, institutional responses to such attacks.