Any film based on a Robert Harris book has a bit of head start. The novelist has such a gripping and clear-eyed prose style that film adaptations tend to get right to the heart of the matter in double-quick time.

Enigma, The Ghost Writer, An Officer and a Spy, The Edge of War – they have all enjoyed success on the big screen, and I’m still waiting excitedly, though I suspect vainly, for the fabled production of Pompeii. For a while back in the mid-00s, that was on course to become the biggest-budget European movie in history.

“Yes, he’s a gift to adapt but there are still may traps along the way, many different paths to take,” says Peter Straughan whose script for the forthcoming film Conclave, based on Harris’ 2016 best-seller, is a clear and justified favourite for awards nominations, along with, I would wager, nods for Ralph Fiennes’ performance in the lead role and several others besides, not least Best Picture.

Straughan, working with All Quiet on the Western Front director Edward Berger, has crafted something pretty special here, a pulsating, edge-of-the-pulpit, juicy, gossipy political thriller set in the Vatican during the election of a new Pope, following the sudden but unsuspicious death of the old one. Following tradition, all the world’s cardinals – 113 of them in this case – are convoked to Rome to sit and debate and choose God’s next representative on earth. Honestly, it’s way more exciting than it sounds.

I’m no papal expert but in the last few years, I’ve seen the 2011 Nanni Moretti film Habemus Papam; the Paolo Sorrentino series with Jude Law, The Young Pope; and the 2019 awards contender with Anthony Hopkins and Jonathan Pryce, The Two Popes, so didn’t feel there was much space or need for more on-screen pontification, even though there are one and a half billion Catholics in the world.

“That wasn’t our tagline,” says Straughan. “It wasn’t ‘If you love Catholicism, you’ll love this movie’. Although if they all come, we won’t be upset, and nor will they, we hope.”

I went in somewhat dreading it but came out exhilarated and reeling from the final reveal. (I hadn’t read the book and if you haven’t yet, then in this case, it’d probably be worth testing out that old, lazy cliché: wait for the movie.)

“We always had in mind those 1970s Hollywood conspiracy thrillers,” says Straughan. “All The President’s Men, that kind of thing, with the paranoia and the fear of being overheard, all whispers and echoes. Ultimately, it’s a film about trust, in people and in God, and it felt to me that among all these men of faith, there was a lot of mistrust going on here.”

And that’s what really makes Conclave so engrossing. For a film about men of God, there’s a lot of weakness, venality and doubt. A lot of doubt. There’s even a terrific speech, delivered by Fiennes’ Cardinal Lawrence on the eve of the election, asking the conclave to elect a “Pope who doubts”, because a Pope who doubts must have faith.

Says Straughan, with a chuckle: “I know, it’s pretty radical, isn’t it? And what he’s saying there is that doubt keeps us together while certainty drives us apart. The polarisation of right and wrong, good and bad, well that feels very timely and necessary in these times.

“But this film is really about religion and faith which big movies don’t always deal in and it ponders those questions seriously, so if you are a devout Catholic, you might have pause for thought, but it’s a serious inquest into the meaning of life.”

Straughan says this “Sermon of Doubt” was the passage in the book that hooked him into writing the screenplay, attracted to what he felt was a radical deconstruction of the system but seen from deep within. “It’s a quiet sort of radicalism, a generous and kind approach and I’m drawn to that.”

I suggest to him that it reminded me of another adaptation of his, from another literary source, that of Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy, which earned him an Oscar nomination in 2012, where Gary Oldman’s George Smiley is also a kind of quiet radical, a loyal servant like Fiennes’ Lawrence, who must now interrogate and dismantle the very system to which he has dedicated his life’s work.

Both films are set in sequestered worlds, dark rooms full of murmurs, and where the patriarchy is in full and uncontested flow. “It’s a very helpful comparison,” admits Straughan. “I’m obviously drawn to these stories of loyalty and betrayal.

“They’re both reluctant demolition men, Smiley and Lawrence. Smiley doesn’t want to face what he knew all along was the truth, that there was a rottenness at the core. So Lawrence interrogating faith is a similar probe. Smiley is loyal to the dead Control who he realises had a grand plan; and Lawrence is loyal to the dead Pope and that he must carry out his dying wishes.”

Those same machinations are also currently on display in Straughan’s equally impressive screenplay to Wolf Hall: The Mirror and the Light, which is playing out on BBC Two every Sunday evening in the old-fashioned manner, with Mark Rylance as Thomas Cromwell working his way up through the treacherous court and whims of King Henry VIII. At the end of episode one, Cromwell allows himself a rare pat on the back. “I’m a butcher’s dog, give me a bone to guard and I will guard it,” he says, exhibiting that strand of loyalty and devotion that’s so tested in Smiley and Lawrence and which draw such meaty, dramatic performances from the actors entrusted with Straughan’s words.

I ask him why he might be drawn to such a theme. Was he ever betrayed? His response is, to me anyway, quite startling, an anecdote remembering his Catholic upbringing. “I do remember as a child being in the garden by myself, playing the crucifixion of Jesus, and I was Jesus on the cross, consummatum est. I think that fundamental story of Judas betraying Christ was very primal to me as a child.”

That’s some serious self-therapy there, I say, adding that it’s very unlikely we would have got on as children. I would not have been knocking on his door asking if Peter wanted to come out and play football.

He laughs. “No, I guess I was quite serious as a kid. But I think it was Easter Sunday, to be fair.”

There is one great betrayal in his personal life, I suggest, and that’s the death of his wife Bridget O’Connor, with whom he co-wrote his early screenplays and who died from cancer in 2010. Tinker Tailor is dedicated to her. Such a loss would make anyone question their faith, I would think.

“I’m certainly loyal to the past and to her memory,” he says. “You remain attached to them and the love you had for them. And she’s still a voice on my shoulder when I write.

“We used to have studies next door to each other and I’d finish a scene and knock on her door to get her opinion and I think I probably still do that mentally. But do I see her death as a betrayal? I have never made sense of it, put it that way. But death happens – if there’s a higher plan, I can’t answer that.”

Conclave asks these questions, constantly testing the strength and moral fibre of the candidates. To be honest, they hardly behave with saintly probity. They’re spying on each other digging up dirt and secrets, scratching at surfaces to find fault.

It’s not surprise to anyone that the Catholic church is not blameless here but this film isn’t an investigation, in the way, say, the Oscar-winning Spotlight revealed child abuse, or European films such as Peter Mullan’s The Magdelene Sisters and Francois Ozon’s By The Grace of God looked at the sins of the past.

In fact what makes Conclave so pertinent is its gaze on politics. I saw the film on the eve of the recent US election and of course its mud-slinging, horse-trading and smear campaigns chimed loudly with what was going on outside the film’s Vatican walls and off the screen.

“It shows politics has ever been thus, I think,” says Straughan. “It’s about the extent to which someone will compromise to win votes, the extent to which power corrupts, the difficulty between who seems a virtuous candidate and who is the monster of ego.

“It’s part of the political process. We wanted to show that, and not have it be relevant to any particular campaign, in the US or in Europe, because it’s actually universal.”

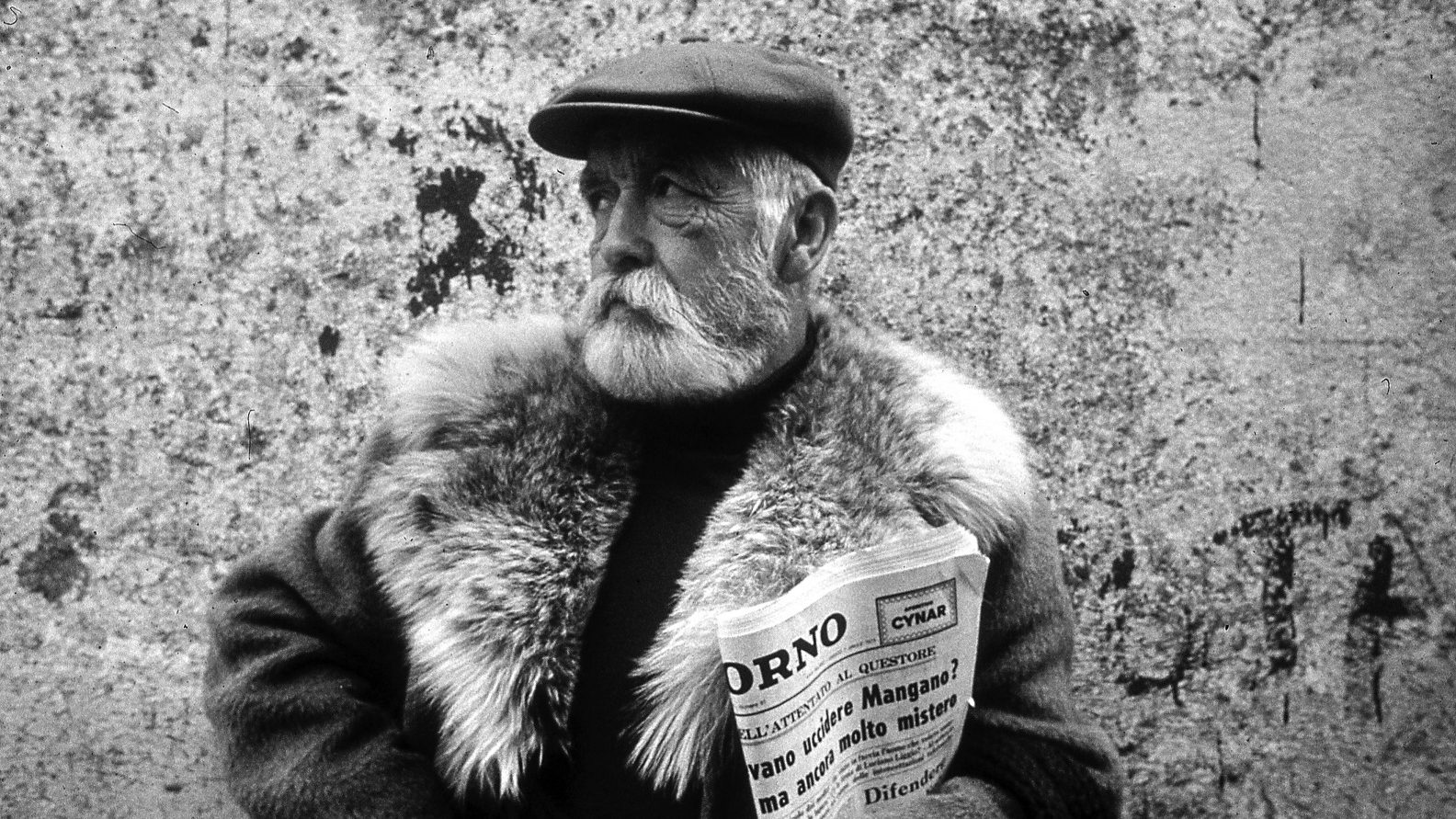

Fiennes’ Lawrence is full of false modesty, claiming he doesn’t want to run for the top job; Stanley Tucci’s Bellini is a likeable reformer and a popular choice; John Lithgow’s Tremblay is a traditionalist who gains momentum and there’s a reactionary Italian hardliner, Tedesco, played by veteran actor Sergio Castellito.

There is also Adeyemi from Nigeria, played by Lucian Msamati, a favourite with the African block of voters. And there are outsiders, too, to whom one must pay attention.

One of these is Isabella Rossellini’s Sister Agnes, a head nun who oversees the Vatican housekeeping and catering and staff and who brings a note of feminine anger and protest to the very male proceedings.

I can’t vouch for the film’s religious authenticity, although for verisimilitude’s sake, it was filmed at Rome’s Cinecitta which has a permanent Sistine Chapel set and a few Vatican rooms, so often the place crops up in dramas. There’s plenty of Latin spoken, smatterings of Italian and Spanish too, although the main language is English, which, while handy for Hollywood, is also very likely given the participants are assembled from around the world and English would be the lingua franca, perhaps unofficially.

So while this isn’t a satire, nor is it irreverent, although it is funny and charming about religion and the theatre around it. The film clearly does have a view on this conclave as a slightly ridiculous pageant, with the industrialised production of black or white smoke puffed out of the chimney each day – we don’t see much of the gathering crowds outside awaiting the signal. And ultimately there’s a clear leaning to favouring a more progressive and tolerant approach to religion and doctrine that might challenge some people’s views.

Straughan says he did write in some of the Catholic kitsch of the Vatican, the plastic pietas and the Jesus tea towels, but that he and director Berger felt that was an easy shorthand, and quite obvious. Their details are more about showing the sacred and the secular intermingling, the traditional and the modern clashing where the Cardinals hand in their mobile phones, go out for a puff during breaks and, in one lovely thumbnail, show the Pope on the treadmill in the Vatican gym.

“The film runs on the tensions between opposites,” says the screenwriter. “You’ve got the Renaissance splendour of the Vatican, against the bland, almost conference style hotel rooms where the cardinals are lodged, in these bare and plain lodgings, something out of a 1960s Italian holiday hotel, with the marble bathrooms and bare walls.

“I feel it’s so central to Catholicism, that blend of the spiritual and the worldly and it plays out even right at the heart of the religion, in this cloistered conclave that tries to shut itself from the world but can’t quite keep the present or the past from creeping in.”

Ultimately, the film’s job, as a Hollywood awards contender produced in Europe, is to entertain, and it does that brilliantly, surprisingly and intelligently, in a way that practically restore one’s faith in cinema and trust in the simple power of smart scripts, clear direction and superb performances.

If politics and religion let you down, sometimes, it’s just easier to believe in the movies.

Conclave is released in the UK on November 27