At 18, a serious-minded young German from Donaueschingen, a town in the Black Forest near the Swiss border, set out across France, Belgium and the Netherlands. He had been born in 1945, the year those lands were beginning to emerge from the nightmare of Nazi occupation. The first recipient of a new travel scholarship for young artists, the young Anselm Kiefer may have travelled light, but he carried with him what he would often refer to in later life as the weight of history.

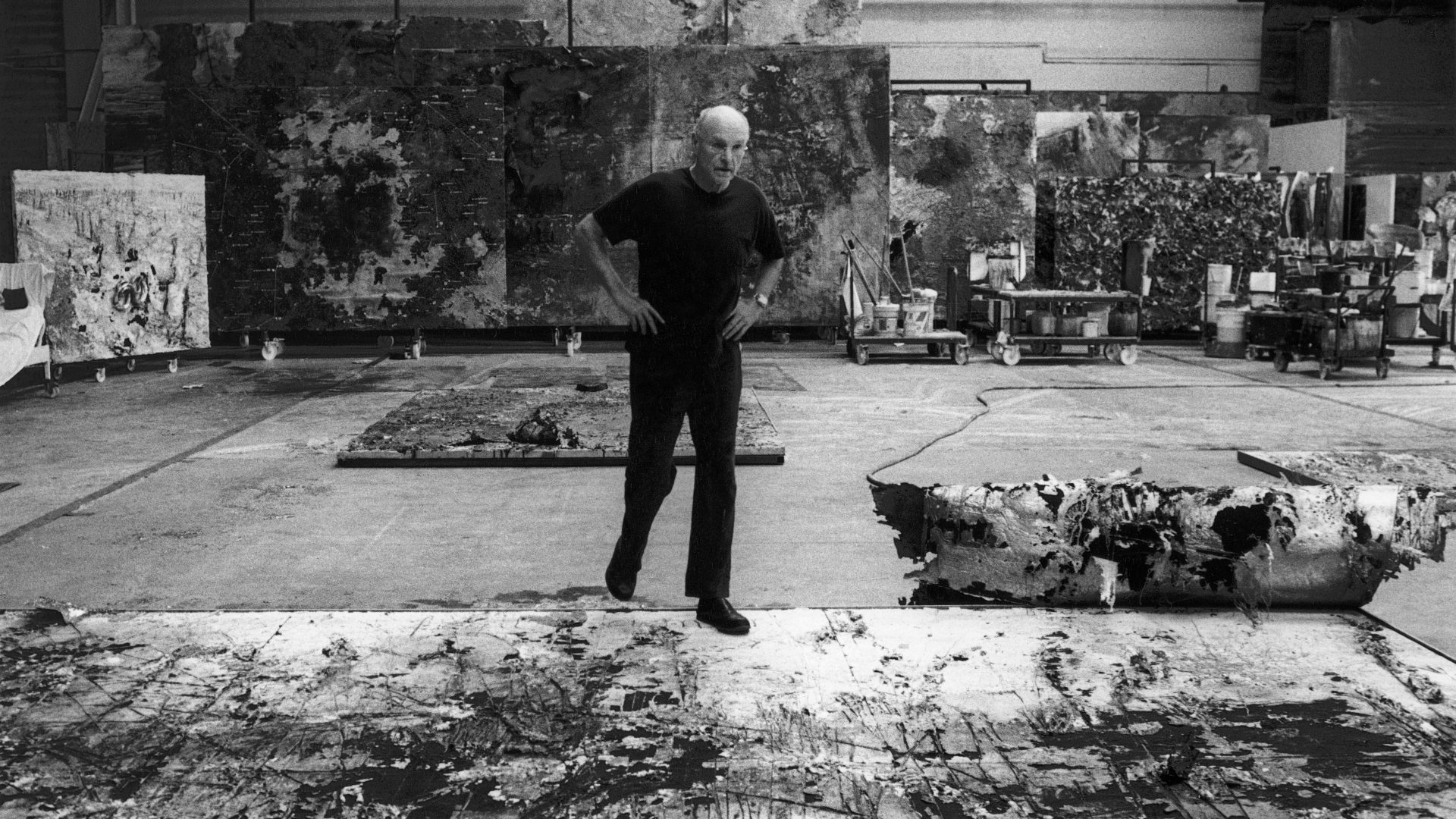

Now, more than 60 years on, two exhibitions in Amsterdam and one in Oxford are showing the work of Anselm Kiefer, covering his early, mature and most recent output. Arguably the most significant living artist, Kiefer’s work is constantly arresting and alarming, while often consoling and unashamedly beautiful. Kiefer calls history an artist’s material, “just as clay is to a sculptor and paint is to a painter”.

The Amsterdam exhibitions take their title from the 1956 song by Pete Seeger, Where Have All the Flowers Gone? The written text – “Where have all the soldiers gone?”; “Where have all the graves gone?” – sprawls across the works that surround the top of the great staircase in the Stedelijk Museum. The five floor-to-ceiling pieces that tower over the visitor are on a monumental scale, typical of Kiefer’s latest and greatest works.

Technically these are canvases, thick with verdigris paint and made sculptural with applied objects, stuck to the canvases like giant collages. Ranks of spattered, degraded uniforms hang from rusting hangers, and some of them would only fit a child. Rein Wolfs, director of the Stedelijk, introduced the artist and his work, with its “weight of the past and uncertainties of the future”, two days before Kiefer’s 80th birthday.

“When the world order seems to be unstable it’s important to think about other unstable world orders,” said Wolfs. “It’s important to use history to explain what’s happening today.”

What’s happening today wasn’t happening when the exhibitions were in the making – not all of it, anyway. But Kiefer’s practice is rooted in the trauma of a childhood in postwar Germany. The burden of his father, in particular – an officer in the Wehrmacht – was always present in his art. Threat, decay and destruction burn from the vast canvases, but glowing in the embers is always the promise of regeneration.

The young Kiefer’s European journey followed in the footsteps of Vincent van Gogh. There are obvious synergies between the two artists, notably in the paradox of the sunflower: at its most glorious and spectacular the sun-seeking flower head is on the point of corruption and collapse. Kiefer depicts the sunflowers in paint and has also stuck withered flowers to the canvases.

Dull, dark seeds will fall to the ground from bowed and blackened heads – but each enfolds a drop of precious oil, and carries the promise of a new crop of breathtaking beauty, mobile, radiant and strong.

The flowers of the joint exhibitions’ title, however, are interpreted by the artist as roses. Pink and crimson petals are scattered on the floor around the Stedelijk installation, some with just the ghost of a fragrance, but all drained of their former voluptuousness, as they crackle under the feet of heedless gallery-goers.

Curators are realistic about human nature. Petals will disappear in pockets and bags, to be replaced by patient gallery staff. Everyone wants a piece of Anselm Kiefer. “Only these are not Anselm Kiefer,” says Wolfs.

After his youthful Van Gogh pilgrimage, Kiefer confronted his country’s – and his own family’s – past by posing in his father’s old uniform, giving the same stiff-armed salute that has become newly and distastefully fashionable among certain ultra right wing Americans.

Some of the resulting images can be seen in a third Kiefer exhibition, at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford.

These acts of contrition – atoning for the sins of the fathers – seem to liberate Kiefer, not from his share of Germany’s collective memory, but from its negative force. From now on, his images will defer to nature’s positive energy.

“My personal history did not start in the Third Reich,” he says, “it stretches back much further… I don’t view history in a linear way: it repeats itself and we find the same structures and patterns in other cultures, too, such as the Incas. History seems to me instead to be something that widens the further back we go.”

Like his sunflowers, in Kiefer’s early work lie the seeds of what is to come over the ensuing six decades. Certain leitmotifs will recur over and over.

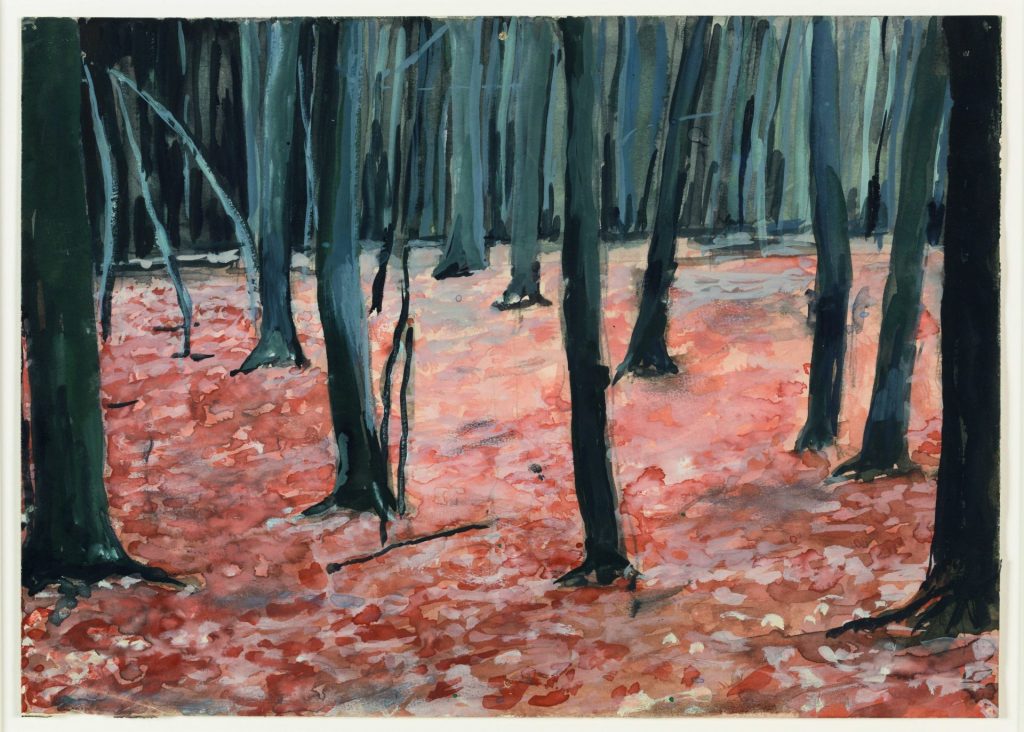

Meanwhile the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam juxtaposes Kiefer’s works with those of their own man, and this emphasises the fact that Kiefer seldom strays far from landscape in its broadest sense. Drawings of rural scenes that date from the 18-year-old’s expedition demonstrate that, notwithstanding the sheer scale and abundance of his later works, in some ways he is a landscape artist at heart. For decades, in works that are loaded with meaning and symbolism, the sky is always up there, the land down there, and the natural order goes undisturbed and unimproved upon.

In 1992, having worked for 20 years in Odenwald, latterly in a former brickworks, Kiefer left Germany and set up a colossal new studio in a disused silk factory in Barjac, Provence. Here he creates installations on an industrial scale, but also cultivates sunflowers using seed brought back from Japan during two years of extensive travels across Asia – during which, he says, he did no painting. The experience also led to a rethink: “I needed a change for my work, and it is easier to change if you go away,” he told Das Kunstmagazin in 2001. “The horizon has disappeared and the materials are clearer.”

Kiefer has no time for abstract art, he writes in the catalogue for the Amsterdam shows. “I find completely abstract art, for example by Wassily Kandinsky, boring and vacuous. I prefer abstract art that retains a hint of representation, like those paintings by Kandinsky in which the transition to abstraction is still discernible, where the struggle is still visible.”

There is no doubt that the later artist appreciates a good struggle, especially if it is natural forces that are at work. In Hemlock Cup (2019), the life has been bleached out of fertile land by the toxic plant that gives German its own version of “poisoned chalice” – Schierlingsbecher or beaker of hemlock.

Farmland under attack is a common motif. The birds that wheel over Die Krähen (The Crows, 2024) resemble a squadron of fighter jets, their outstretched talons like landing gear. You settle into the luxurious gold leaf in the skyline of Under the Lime Tree on the Heath (2019) before noticing a sticky red patch, like a telltale bloodstain at a crime scene. Sometimes the land gets its own back. Also in 2019, the greedy farmer in The Last Load, based, says Kiefer, on a folk tale, collapses under the weight of the grain, having wrested too much from the earth.

Kiefer’s connection to Van Gogh stretches from the soil to the sky. His O Stalks of the Night, with its reference to a Paul Celan poem and its satellites of gold and indigo, echoes Van Gogh’s starry nights. Kiefer’s own Starry Night is another undisguised tribute, with constellations of gilded straw and moons of chaff in a sky of aquamarine.

But rarely in this natural world is there a recognisable being. A rare exception is the snake that winds through the fuselage of a small jet plane, a creature that can shed one skin and start a new life, while man is represented solely by the memoir of an adventurer.

Lead has become a powerfully suggestive material for Kiefer. Having already discovered its potential and alchemic symbolism, he bought lead sheets discarded during the restoration of Cologne Cathedral.

Journey to the End of the Night was first shown in 1990 and continues to make a stomach-turning impact, occupying an entire room. Its title is that of a controversial novel by Louis-Ferdinand Céline, who held antisemitic and fascist views. The sense of a crash landing and the absence of humanity make this a chilling object. Unlike the natural world, it has no built-in regeneration. For that, the viewer looks to the fields and skies recreated on the walls.

When Kiefer asks the question, “Where have all the flowers gone?”, he answers it himself, in his art. The flowers are destroyed, like so much life, by warfare. And although we have learned that, we have not learned to keep the peace.

Anselm Kiefer – Sag mir wo die Blumen sind is at the Van Gogh Museum and Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, until June 9. Versions of the exhibitions are at the Royal Academy of Arts, London, June 28 to October 26 and at White Cube, Mason’s Yard, London, June 25 to August 16. Anselm Kiefer – Early Works is at the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford until June 15