Fruitful work, music and dancing, nourishing food, justice and peace. The benefits and responsibilities of good leadership loomed large above the heads of decision-makers in 14th-century Siena.

Do it like this, and get it right, the exquisitely beautiful and idealistic imagery of Ambrogio Lorenzetti signalled in his 1338 cycle of frescos, Allegories of Good and Bad Government. On the other hand, rule like the characters in the counter image, presiding over Bad Government, and watch an unjust society crumble.

With a ruling system that was ingeniously simple in some respects – nine elders at a time held office in perpetual rotation – the real-life society outside the Palazzo Pubblico was not far removed from this high-minded allegory. Siena had hit the jackpot in terms of productivity, its many workshops at full tilt, pooling skills to meet insatiable demand.

Around the tiny city state, vast churches were being raised for monastic orders, and these were in urgent need of religious works of art on a proportionately lavish and imposing scale. Furthermore, a commitment to the Virgin Mary, believed to be the saviour of Siena, prompted innumerable votive pieces.

Siena had no problem espousing both its republican ideals and its religious convictions, because the two had combined in 1260, when, on the eve of battle with superior forces from Florence, the keys of the city were offered to the Virgin in exchange for her support. On winning the ensuing Battle of Montaperti, Siena honoured its debt by dedicating the cathedral, where the pledge had been made, to Mary. The governors were also happy to encourage religious foundations that undertook charitable works as part of their vocation, sparing the public purse.

This flood of art, much of it dominated by images of the Virgin Mary, came at just the right time for a succession of creators whose work can be seen to this day, both in situ and in collections worldwide. One of the finest holdings is at the National Gallery in London, where a new exhibition celebrating this boom industry features many of its own masterpieces.

Alongside them will be loans from the city of Siena itself and collections worldwide, including that of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, where the exhibition, Siena: The Rise of Painting 1300-1350, has already been seen.

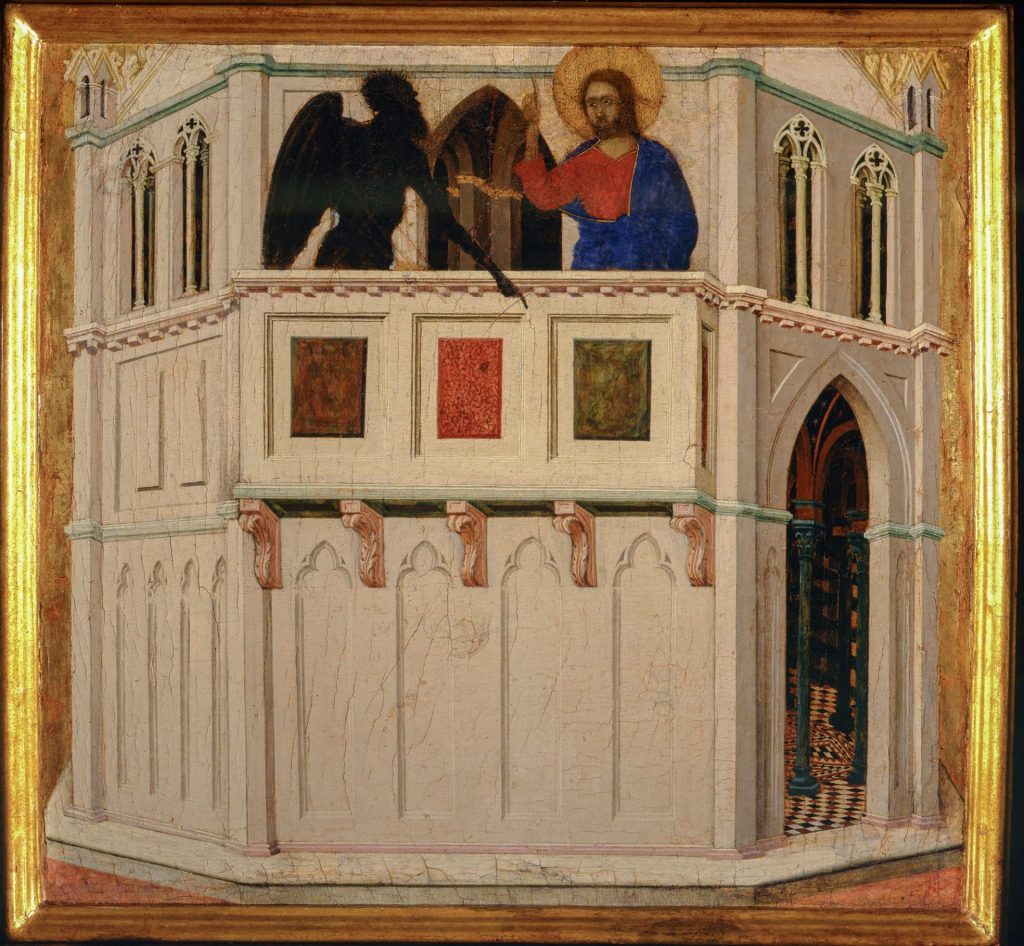

The Annunciation, 1308-11

While much of Siena’s finest surviving art is too delicate or too deeply embedded to move, many precious pieces from the prolific hands of four key artists will be seen and in some cases reunited in an unprecedented display of awe-inspiring inventiveness of composition and intricacy of craftsmanship. Portable pieces echo art that, 700 years on, draws visitors from all over the world to the tiny Tuscan city, where the Pinacoteca, already an important museum and gallery, is to benefit from more funding and status by being elevated to independent, autonomous status, putting it on a par with national museums and sites such as the Uffizi in Florence, the Brera in Milan, Capodimonte in Naples, and Pompeii.

At the Pinacoteca, at the Museo dell’ Opera del Duomo and across the city, stupendous altarpieces can still be seen in situ, but their very complexity enabled, on occasion, their breaking up into myriad smaller pieces, just the right size for the homes of private collectors or the fine rooms of the world’s galleries.

Since its heyday in the 1300s, the population of Siena, at around 50,000 has hardly changed, an indication of the intensity of artistic creation then, and of the daily influx of tourists today, for by day the streets are packed, even though the city tends to empty at night as the charabancs move on.

Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s highly detailed illustrations of enlightened and poor practice are currently under restoration. The pioneering project, which concerns not only the surface of the great frescoes but also structural improvements, will take many years. Because of this, visitors are able to climb a scaffolding and come face to face with the virtuous and happy characters, as well as the cruel and dejected.

Here is detail of charm and sophistication that might escape the eye when viewed from the normal floor level. The dragonfly motif on the sinuous gown of a dancer – possibly one of the daughters of Venus – would not look out of place on the catwalk or in the décor of one of the Bloomsbury group.

Today we like to attribute work to a single artist, and to be reassured that she or he, and none of their assistants, is solely responsible for a piece. The leading artists of the 14th century were not under this pressure: it was accepted that a work of art might be a collegiate effort, driven by a master but with other hands in play. Siena: The Rise of Painting concentrates on four such masters: Good Government’s Lorenzetti and his brother Pietro, Simone Martini and, in the vanguard, Duccio.

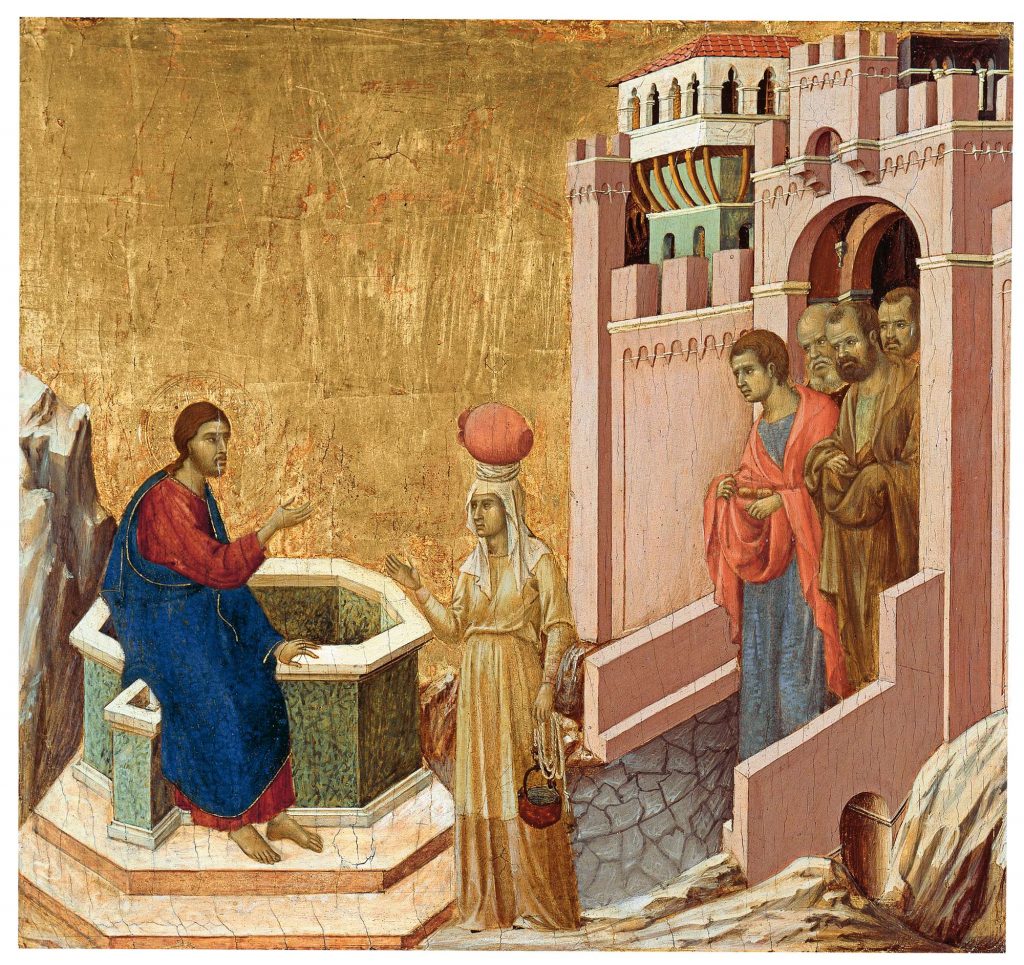

The exact birth date of Duccio di Buoninsegna is unknown, but when he died in 1319 he left a blueprint for religious art that was followed for generations to come. But even he did not spring fully formed from nothing. Frescos discovered only in the 1990s in the crypt of Siena cathedral clearly influenced the compositions of Duccio, who began to produce art on an almost industrial scale. Arguably it was not Andy Warhol, with his mass Marilyns who devised the Factory, but Duccio, 750 years before.

While the National Gallery itself owns some of the finest examples of his work, a feature of the exhibition will be the reunited scenes, small, story-telling panels, from the reverse of his Maestà, the greatest treasure in the cathedral museum. The Maestà is the earliest surviving double altarpiece, with front and rear, albeit fragmented.

The artists worked on wooden panels, the best support for the lavishly applied gold leaf, and the work was once paraded through the streets of Siena. Now scattered into collections worldwide, their reassembly is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to get close to the master at work, for it is possible to detect which of the finely worked figures were by Duccio himself, and which were by other artists who followed his example, while striving for consistency. These scenes of human encounters and dilemmas taking place on an almost domestic scale have a timeless quality.

La Resurrezione,

c.1320-1330

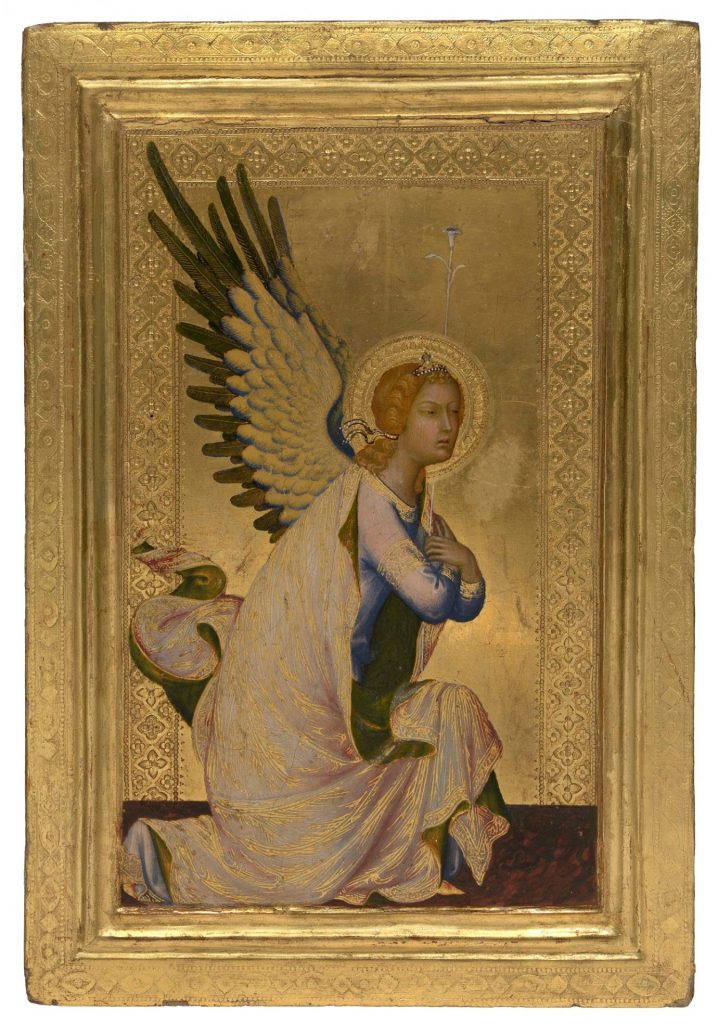

But it was Duccio’s successors who brought to life a world of saints and secular figures, with the help of a device that sprang from one of Siena’s great strengths – textiles. Figured silk was a precious, highly decorative fabric that Simone Martini and the Lorenzetti brothers would never have owned, but would have seen, particularly in liturgical vestments. They understood how its folds, curves and interrupted repeat patterns lent volume to the people wearing opulent garments.

One of the showstoppers of Siena: The Rise of Painting is an altarpiece loaned by the church of Santa Maria della Pieve in the Tuscan city of Arezzo, by Pietro Lorenzetti. Magnificently restored in 2020, it was created with costly gold, silver and lapis lazuli, and even with some elements missing it normally dominates the church from the high altar in the elevated east end.

Pietro’s Madonna is sumptuously wrapped in a flowered cloth wound over ermine, the twists and turns of the worked cloth putting flesh on the bones of the Virgin. Her slender fingers press dimples into the soft flesh on the child she supports, while the babe clutches the trim of her garment, his outstretched arm completing a dialogue between mother and child. We know that Pietro was proud of the piece. He signed it twice, in Latin, once below the Virgin with the words: Petrus Laurentii hanc pinxit dextra senensis – “dextra” indicating not just his right hand but dexterity.

This mastery with fabric is exhibited too by Simone Martini, who witnessed a flood of lavishly ornamented cloth from the East into Siena, with vivacious motifs that exceeded in inventiveness the geometric repeats of traditional Italian designs. These were swiftly emulated by local weavers. He also enriched his work with sgraffito work on gold, creating texture and depth by digging into gold leaf.

Such lavish dress was reserved by Ambrogio Lorenzetti for the figure of Justice that dominates his Good Government, Bad Government. He had the advantage of observing the developments of his contemporaries, and also went to Padua to learn from Giotto’s fresco cycle in the Scrovegni Chapel. While much of Good Government has deteriorated over its seven centuries, the scale of the figure of Justice, in comparison with the Lilliputian citizens she judges, her multiple framing, by sky, throne and garments, and the extravagant use of costly crimson elevate her to the highest station, above languid if attentive Peace. This was a warring state, after all.

As Jules Lubbock points out in a searching and combative new book on the cycle, those elders on rota, the Nine, were self-interested bankers. And the 24 citizens upholding a symbolic cord passed on by Justice must keep in line, or else everything foundered.

Medieval Siena was no place for disruptors. It was a place where art mattered intensely, its creation supporting many. The lessons of Good Government, Bad Government still stand.

Siena: The Rise of Painting 1300-1350 is at the National Gallery, London, from March 8 to June 22. Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s Good and Bad Government Reconsidered by Jules Lubbock is published by Ad Ilissum