They studied or lived in Berlin, Dresden, and Paris, travelled through Italy and Spain, and rubbed shoulders with European artists visiting New York. Almost without exception, the artists who have come to represent modernism in Brazil, however immersed they were in their own culture, were profoundly influenced too by what was happening on this continent.

Early 20th-century movements, especially Cubism, cast a long shadow across the largest country in South America, as an exhibition at the Royal Academy of Arts illustrates in its celebration of 10 artists little known outside their own land. While the title of Brasil! Brasil! The Birth of Modernism may be bold to the point of exaggeration, the show itself unfurls engagingly enough, while unwittingly throwing the light back on to Europe over and over again.

Where the Brazilian artists really scored was with their unique insight into a time of massive social and political change such as few European countries have experienced. A colony of Portugal from 1500 to 1815, it was only in 1888 that slavery was finally abolished, too late for the four million West Africans brought forcibly to Brazil.

After 75 years of imperial rule, it became a republic from 1889 onwards and was neutral during the second world war – until the sinking by Germany and Italy of dozens of trading vessels in 1942 killed 1,600 mariners.

Thereafter, Brazil declared war on the axis powers and committed considerable industrial resources and military assistance to the allies, sending warships to take part in the Battle of the Atlantic and deploying more than 27,000 troops to fight in the Italian campaign, the only South American country to send soldiers overseas. By the end of the war, Brazil emerged as a significant power, at the cost of 31 merchant vessels, three warships, and 22 fighter aircraft.

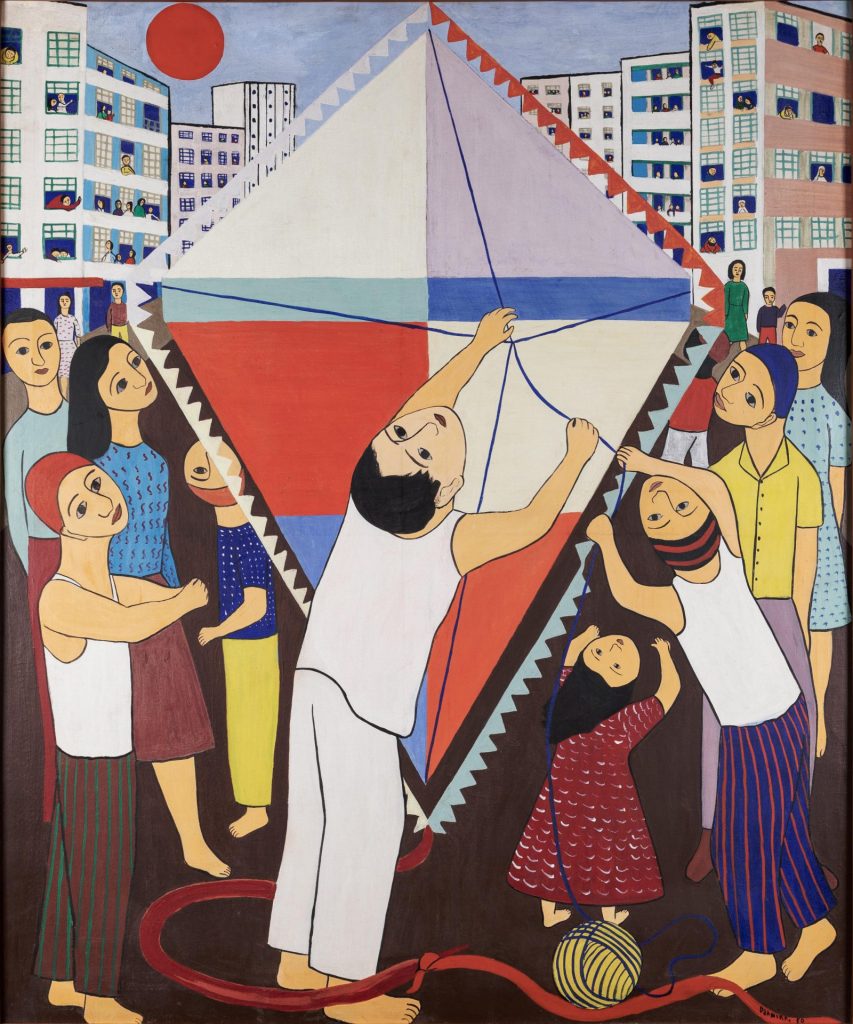

This was the country’s recent history when artists such as Candido Portinari painted his Migrants (1944), memorialising the gruelling trek of three generations of starving, displaced people, bleached of life. The malnourished, pot-bellied child and desolate father sport cruelly jaunty garments, the mother carries all their worldly goods on her head, the skeletal grandfather with his staff echoes the Grim Reaper as a distant vulture’s outspread wings turn his staff into a scythe.

Portinari (1903-62) is typical of those artists who absorbed European influences and blended them with the culture in which they were raised. The son of poor Italian immigrants, he was brought up on a coffee plantation but went as a free student to the Escola Nacional de Belas Artes before winning a travel scholarship that took him across Europe. There he studied the old masters and modern movements, combining elements of both practices in his own painting.

He was considered an important painter of religious art, and his hard-hitting social realism confronted racism in particular. In the 1950s he created his War and Peace mural for the United Nations headquarters in New York and, recognised internationally, was considered Brazil’s most important artist.

The trajectory of Lasar Segall (1889-1957) was completely different. Growing up in the large family of an affluent merchant in Vilnius, Lithuania, he studied in Berlin and Dresden before setting out to São Paulo to visit a sister and stage a successful exhibition, his European credentials his calling card.

Shuttling between Germany and Brazil, he settled for good in São Paulo in 1924, marrying a wealthy heiress. But even protected from the poverty experienced by many of his new countrymen, his observations of hard lives and his own memories of losing his mother in his teens made his work acutely sympathetic. His sepia-toned Pogrom (1937), recording antisemitism in Stalinist Russia, is as distressing as Portinari’s Migrants, bodies piled high like litter, blameless babies robbed of life.

In later years, Segall found solace in forests, and in the deep, earthy colours of their vertical lines and slivers of light. This geometry, cut and rearrranged, is found in the wooden shacks of the shanty town that sprang up after the war as destitute rural families headed for the city. The human figures in Favela (1954-55) are stacked in their tiny boxes, a single palm tree breaking through the man-made thicket. A woman bearing a baby, a bundle, or both, has no place to go.

Not surprisingly, Brazilian female artists in the early 20th century had to work hard to be noticed or valued. Two who stood out were more or less contemporaries: Anita Malfatti (1889-1964) and Tarsila do Amaral (1886-1973).

Both were born into comfortable homes, but Malfatti’s family hit hard times with the death of her father, and she began painting for a living, aided by an uncle who arranged her studies in Berlin. A major exhibition in Cologne in 1912 exposed her to the work of Van Gogh, Cézanne, Gauguin, Bonnard, Matisse and other trailblazers.

“I saw painting for the first time only when I arrived in Europe,” she later said. “When I visited museums, I was made dizzy by what I saw.” Her freely coloured nudes, angular portraits and rugged coastlines show the impact of that experience.

But returning to Brazil in her late 20s, Malfatti was stung by criticism of work that was avant-garde for the time. Even the sympathetic uncle turned against her, denouncing her bold canvases as “Dantesque” and banning them from his house.

At first, she soldiered on, but a damning review in 1917 stopped her in her tracks. Nevertheless, she won a scholarship to study further in Europe, spending five years in Paris, learning from Maurice Denis, and returning with a variety of styles that, taken together, make her a difficult artist who cannot be pigeonholed.

Like Portinari, Tarsila do Amaral grew up among coffee plantations, but her family were not labourers, they were landowners, and her affluent upbringing afforded private art tuition in São Paulo before a move to Paris and the Académie Julian. On returning to São Paulo she, Malfatti, Menotti Del Picchia, Mário de Andrade and Oswald de Andrade (the two were not related) – formed the Grupo dos Cinco.

She and Oswald set up home in Paris a year later, but like Malfatti she saw her fortune slip away, this time in the economic crash of 1929, and her work became more socially aware. In Segunda Classe (Second Class, 1933) exhausted adults and children with meagre possessions line up, barefoot, by the carriage that labels their low status. Today, however, she is more recognised for her decorative paintings in fondant pinks and blues.

Whatever class they travelled, the 300,000 citizens of São Paulo had few cultural outlets to enjoy. In 1916, at the time of Malfatti’s much-criticised exhibition, there was only one museum in the city, showing a few outmoded and unchallenging pictures, and no permanent gallery.

Exhibitions were staged, explains Giancarlo Hannud in the exhibition’s catalogue, in hotels, offices and shops. But thanks to those who experimented with modern art, and the growing numbers and influence of their enlightened collectors and supporters, a time of rapid change lay ahead.

In 1944, Brazilian artists were showcased in a landmark exhibition of more than 150 works at the Royal Academy in London, organised by Brazil’s then-foreign minister, Oswaldo Aranha. Artists were encouraged to donate their work to raise money for the RAF Benevolent Fund. Furthermore, more than 20 artworks were secured and allocated across British collections by the British Council.

This was the first-ever exhibition of Brazilian art in Britain and highlighted the considerable role Brazil was playing in the war effort. The British royal family were among the 100,000 people who turned out to see the exhibition before it toured Scotland and Paris – partnered with a second exhibition showing three centuries of Brazilian architecture.

The current Royal Academy show marks 80 years since that groundbreaking exhibition, and reunites work shown by artists including Portinari and Do Amaral. But curiously, little mention is made in Brasil! Brasil! of another big step for Brazilian art – the launch in 1951 of the Bienal de São Paulo, the second longest-established biennial in the world after Venice.

One artist who did exhibit most successfully in the second such event, in 1953, was Italian-born Alfredo Volpi (1906-88), who was named joint winner, apparently after an intervention by the visiting British art historian Herbert Read. Volpi’s family had emigrated to São Paulo when he was only two, and he left school at 12, becoming a painter and decorator to help the family finances, and experimenting with the materials of his trade as a self-taught artist. His initially naturalistic style became more and more abstracted into pure geometry, untitled compositions from the 1950s onwards enjoying the rhythm of well-balanced forms dominated by rich blues.

Another biennial exhibitor was dentist-turned-artist Rubem Valentim (1922-91). He was influenced by the West African culture around him as a child in Salvador de Bahia and many of his motifs and vibrant colours are inspired by what he defined as Afro-Amerindian-Northeastern-Brazilian iconology. This exhibition’s modernist credentials may be in question, but it holds up a brightly framed mirror to multiculturalism.

Brasil! Brasil! The Birth of Modernism is at the Royal Academy of Arts, London, until April 21. The 36th Bienal de São Paulo, entitled Not All Travellers Walk Roads – Of Humanity as Practice and curated by Bonaventura Soh Bejeng Ndikung, opens in September