“Right, God is with us,” intoned the conductor of my local choir. “He should be. We’re singing His music.”

No, we don’t have divine protection. It was just the signal to launch into John Tavener’s haunting, Byzantine-inspired God is With Us, which was part of our concert repertoire of Latin, English and French compositions.

All with Christmas or other religious themes. All His music.

This is always perplexing for my teenage children, both tending to the less religious side of Richard Dawkins. Why do I always sing requiems, masses, songs about Jesus and the valley of death – with the same Gloria In Excelsis Deo, Sanctus and Agnus Dei in the lyrics – for practically every concert?

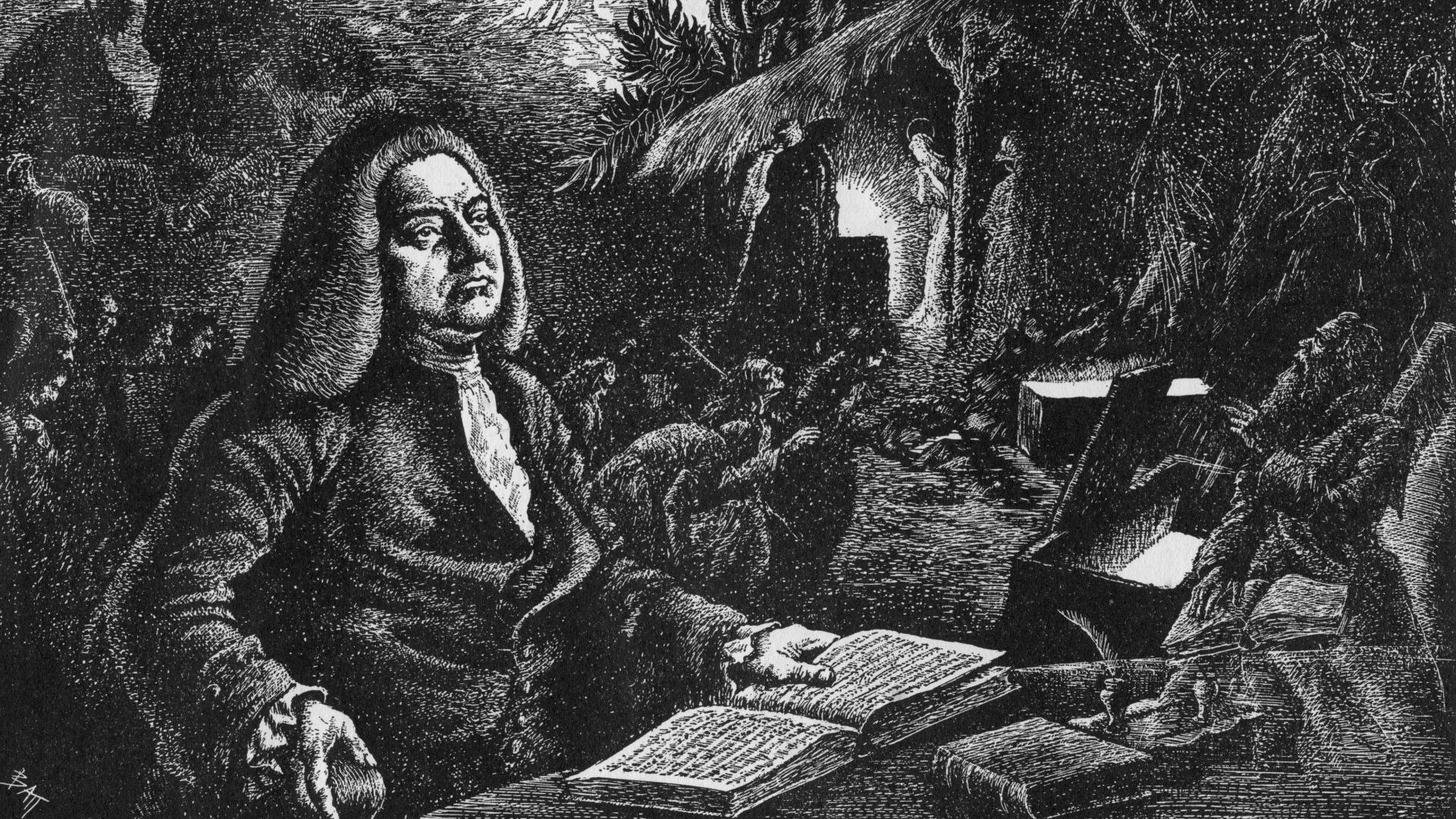

It’s a question asked regularly, especially at this time of the year, with performances of Handel’s Messiah, carols in town squares and songs such as Boney M’s Mary’s Boy Child blaring out as we shop.

It’s the 21st century. Church attendance, in the UK at least, is dropping every year. Shouldn’t we sing something else instead?

My non-scientific answer is that I simply love singing four-part harmony in classical choirs, and enjoy singing the kind of music written as requiems or masses – the melodies, the harmonies, the drama that ranges from dark and hellish to bright and heavenly.

It doesn’t have to be sacred, but a lot of choral repertoire is invariably religious, not least because many renowned composers worked when that was where the money was.

When frustrated by some of our drab efforts at rehearsals, our conductor reminds us: “Remember, they believed in all this stuff. Sing it like you mean it, for goodness’ sake!”

We may not all believe it now, but, in the same vein, should we not admire the works of Michelangelo and Da Vinci today because they painted religion-themed work and were bankrolled by devout patrons?

Fresh from singing God is With Us, I tuned into an online talk by Matthew Cheung Salisbury, lecturer in music and interim chaplain of Worcester College, Oxford, who was exploring the same question. I was particularly captivated by three examples he gave of sacred music finding relevance in a new world.

One was a project he worked on in Scotland, to create inspirational new works from 12th-century religious music found wrapped around old legal documents, with input from experimental film composer Michael Nyman and the rapper Goldie.

Another was the playing of music in Aids wards in the 1980s, often at night. The New Yorker’s music critic Alex Ross wrote that patients loved the minimalist choral works of Estonian composer Arvo Pärt – modern but sounding comfortingly ancient and otherworldly. They called it ‘angel music’.

More recent is the emergence of ceremonial ‘Honour Walks’, where dying patients, who have agreed to donate their organs, are wheeled around hospital corridors in their beds so everyone can honour them, often accompanied by music.

One touching YouTube video showed the last voyage of an 18-year-old car accident victim, accompanied by live gospel singing.

These examples also speak to our need for ritual. Not only religious, but also every day, like a child’s bedtime, or a morning cup of tea, or event-related, such as favourite tunes at funerals, or singing carols, opening presents, eating turkey and arguing with relatives at Christmas.

Salisbury implied that non-religious students liked attending his choral evensong for the calm and the music, even though they didn’t care for the godly lecturing. As philosopher Alain de Botton suggested in his book, Religion for Atheists, elements of religion are good for all of us.

This tips into Cultural Christianity territory – following religion out of habit – which can get a bad rap for laziness and hypocrisy. But do the benefits of contemplating awe-inspiring architectural spaces and uplifting music, that once served the masses, have to be denied to those flakier about doctrine?

The feeling I experience in places from the Sistine Chapel to Istanbul’s Hagia Sofia may not be borne of religion, but it’s certainly powerful.

Studies of choirs found the singers’ breathing slows, their heartbeats synchronise, their stress levels fall and positive neurochemicals are released. Singing, where the instrument is your own body, can be a spiritual experience. It wasn’t just the religious who were moved when Stormzy, a regular churchgoer, performed a sort of worship by stealth at Glastonbury when he got his audience to sing his hymn-like Blinded by Your Grace. Born-again Christian Kanye West, now known as Ye, has built up a strong following for his Sunday Service, his own form of musical prayer – characterised as religion for the social media age – in which he leads his own choir and invites the likes of Brad Pitt and Justin Bieber to join in.

In France, where the republic’s secularism is almost a religion in itself, the overlaps between holy and heathen can be harder.

Schoolchildren do not sing music with religious heritage, a friend from France told me, recounting her battle to persuade her children’s French school in London to let them sing Christmas carols. “There’s hardly any music in school. You don’t have to be devout to do this,” she said. “They’re missing out.”

That’s a shame. Choral music can form communities and lift the soul. If God is with us, that’s fine too.