He was so far ahead that race organisers were on the point of declaring him missing.

The climb through the Dolomites was always going to be one of the toughest sections of the Giro d’Italia when it was introduced to the 1956 race. The weather gods elected to make it utterly brutal.

Light snow was unusual enough for early June, but when it turned into a full-blown blizzard with shrieking winds and freezing temperatures it was clear the eight-mile climb up Monte Bondone would be an epic task for every rider.

They had already scaled four peaks during the 240km mountain section that day, but Bondone would be a challenge beyond mere racing into the realms of sheer endurance. One rider, however, would produce one of the most extraordinary rides in the history of the Giro.

Just three years earlier, Charly Gaul had been a 20-year-old slaughterman working at an abattoir in Bettembourg, Luxembourg, who spent his spare time winning cycle races – most notably races that involved steep climbs. He was good at them.

Indeed, riding in the Tour of Austria at 17, his first race outside Luxembourg, the teenager set a new record for the 2,500-metre climb through the Grossglockner Pass. “I’d never seen a road higher than 800 metres before I rode the Grossglockner,” Gaul recalled, “but I discovered I was good at climbs like that. I found a rhythm, it felt natural, and I discovered that the higher we went, the colder it got – which suited me.”

Gaul turned professional at 20, joining the Terrot team, but found it hard to adjust to life as a professional rider because so many of the road races on the circuit were conducted largely on flat ground, where he struggled. Gaul failed to finish his first two Tours de France but persevered with his work on the flat to become a more rounded competitive cyclist, winning the 1955 Tour du Sud-Est and finishing third in that year’s Tour de France.

Then came the 1956 Giro and that climb up Monte Bondone. While most riders regarded the day’s ride with trepidation for the five peaks alone, let alone the worsening weather, Gaul sensed his chance to impose himself on the race.

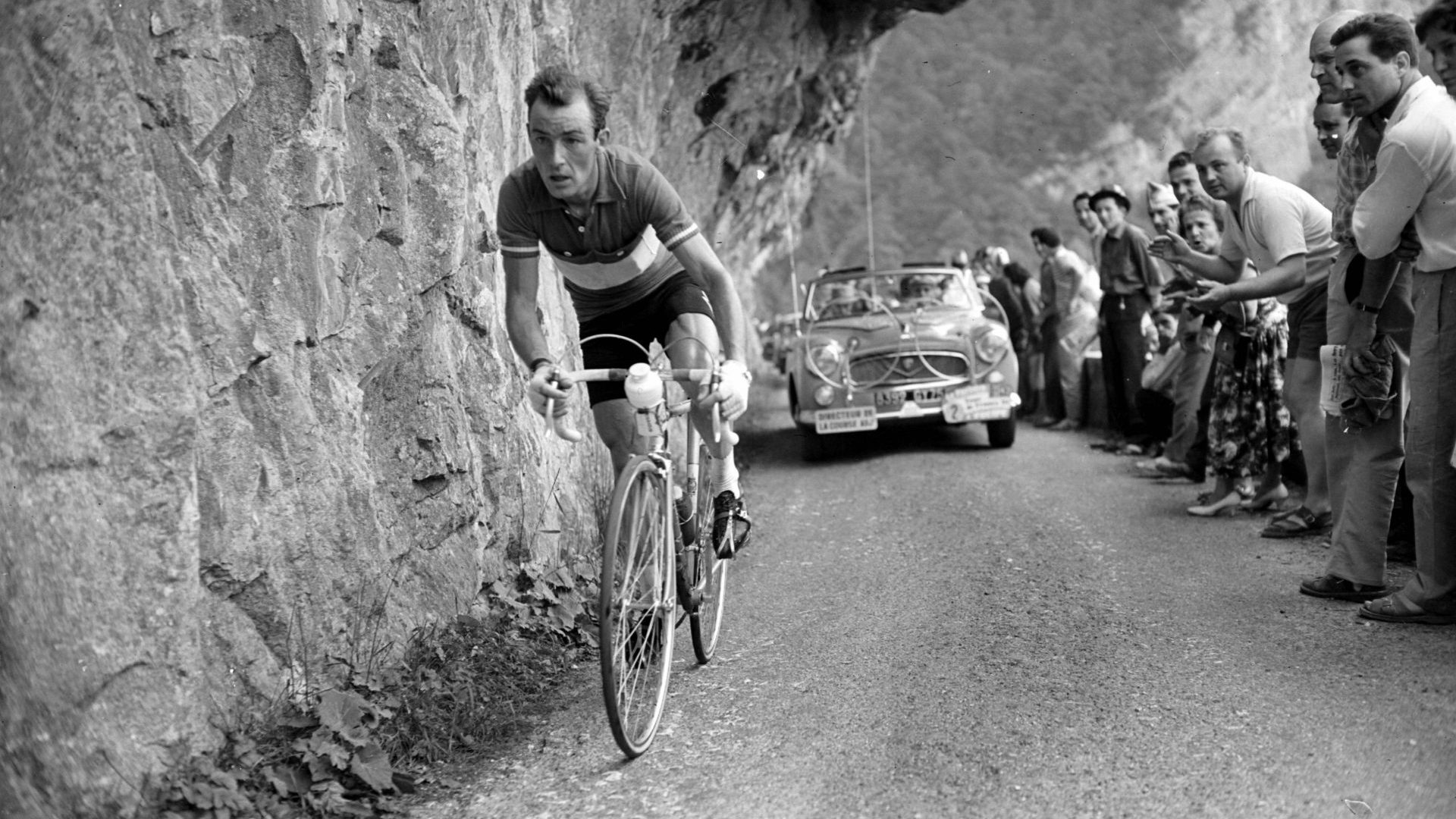

He found his rhythm quickly, and that rhythm was the secret to his climbing success. As one of his great rivals Raphaël Géminiani recalled, Gaul was “a murderous climber, always the same sustained rhythm, a little machine with a slightly higher gear than the rest, turning his legs at a speed that would break your heart, tick-tock, tick-tock, tick-tock”.

As the conditions worsened, riders began to drop out. Race leader Pasquale Fornara found shelter in a farmhouse, while in villages along the route bicycles could be seen outside inns as stricken riders sought warmth and sanctuary from the freezing conditions. Yet still Charly Gaul, wearing shorts and a short-sleeved shirt, rode on, rhythm unbroken, the blizzard stinging every exposed part of his body.

While the weather deteriorated, Gaul increased his lead until he was more than 10 minutes clear of his nearest challenger. Race officials, certain that nobody could make such progress, feared he had gone missing somewhere on the course and was in danger.

Then a bicycle was spotted outside a ramshackle trattoria way ahead of where even his team management had considered he could be. Yet there he was, wrapped in a blanket, carefully being given sips of hot coffee, conscious but insensible with cold and exhaustion.

After a massage, a dowsing with warm water and a change into fresh clothes, Gaul set out again into the blizzard, finding that rhythm, making relentless progress to the top of the mountain and finishing the stage more than 12 minutes ahead of the previous year’s champion, Fiorenzo Magni. That extraordinary ride catapulted Gaul from 11th place in the race to become overall leader, a lead he would not relinquish. Charly Gaul had arrived.

The intensity he displayed in the saddle was an extension of his personality. He was spiky, surly and could bear a spectacular grudge.

During the 1957 Giro, he and fierce rival Louison Bobet stopped to urinate at the side of the road. Etiquette dictated Bobet wait for Gaul to finish rather than take advantage of a call of nature but Bobet rode off, triggering in Gaul a deep-set grievance against both him and teammate Géminiani, whom he considered complicit.

“I will take my knife and make sausage meat out of you,” the former slaughterman told Bobet and Géminiani afterwards.

In the following year’s Tour de France he did exactly that, at least metaphorically. Trailing race leader Géminiani into the mountain stage through the Chartreuse Massif, that morning Gaul took Bobet to one side.

“To make it easy for you, I will tell you what climb I will attack on today: the Col du Luitel. I will even tell you on which bend I will attack.”

He did, too, in a rainstorm, attacking exactly where he said he would and not only making up an eight-minute deficit on Géminiani but converting it into an eight-minute lead of his own, a 16-minute turnaround that proved enough to keep Gaul in the yellow jersey all the way to the finish line in Paris.

After retiring in 1963 he briefly ran a cafe in Luxembourg-Ville, but found the constant public interaction tiresome, leaving him longing for solitude. He sold the cafe and decamped to a remote cabin in the Luxembourg Ardennes where he remained, more or less a hermit, for the next 25 years. Visitors who tracked him down, especially journalists, were soon made aware their presence was not welcome, but he had never been happier.

“I didn’t travel much,” he recalled towards the end of his life. “I said to myself, you’re at peace here, you’re happy. There’s nothing but trees and water. I spent my days planting vegetables and the deer came to eat at the end of my garden.”

Eventually, however, love drew him back into the world, marriage in 1983 prompting a return to the city and a job as an archivist at Luxembourg’s Ministry of Sport. There he would spend hours immersed in the days that made him, replacing the noise around him with the sound of his own laboured breathing, the hiss of tyres on tarmac, the whirr of the chain as he forced himself onward, climbing relentlessly to glory.

“A sad, timid look on his face, marked with an unfathomable melancholy,” was how one rival described Charly Gaul. “He gives the impression that an evil deity has forced him into a cursed profession.”