There was, back in the housebound days of the deepest lockdowns, a Great

Typing at large throughout the land. The faint clatter of keyboards became part of the national soundtrack as scores of people decided the curtailing

of social and in many cases work activities was just the opportunity they needed to finally write that novel, or those short stories, or pour their anxiety about this unfamiliar new world into verse.

Some finished their masterpieces, others abandoned them before the end, still more barely got a few words down before deciding that, all thing considered, sourdough was probably more their thing.

What nearly all these aspiring writers had in common was a degree of uncertainty about what they were doing. Creative writing can be an intimidating prospect, especially when you weigh up the empty page and flashing cursor against the sheer amount of brilliant, challenging, entertaining and thought-provoking books already out there in the world.

What most people setting out on their writing odyssey require is advice. Good advice. Reliable advice, preferably from someone who knows what they’re talking about. There is almost as much advice out there as there is literature and the trouble is, most of it is bollocks.

There is always a healthy debate to be had about how much you can really teach people about writing. There is no defined right way to do it and if there was, literature would be stupefyingly dull because everyone would be writing the same thing.

What, then, separates the good advice from the bollocks? Usually, it comes down not to setting out a list of rigid rules to be followed, but instead sharing lived experience. There are a whopping number of ‘how to’ books out there and the good ones are far rarer than the useless. The best ones are usually accounts by writers of how they work and what suits them. Not telling you how to do it, but telling you how they do it.

This can range from the pithy apercu – “Writing is easy,” said the American novelist Gene Fowler. “All you do is sit staring at a blank sheet of paper until drops of blood form on your forehead” – to the detailed analysis. Stephen King’s book On Writing is a good place to start, as is Becoming a Writer by Dorothea Brande. A book that should now be added to that list is How to Start Writing (And When to Stop) by Wisława Szymborska.

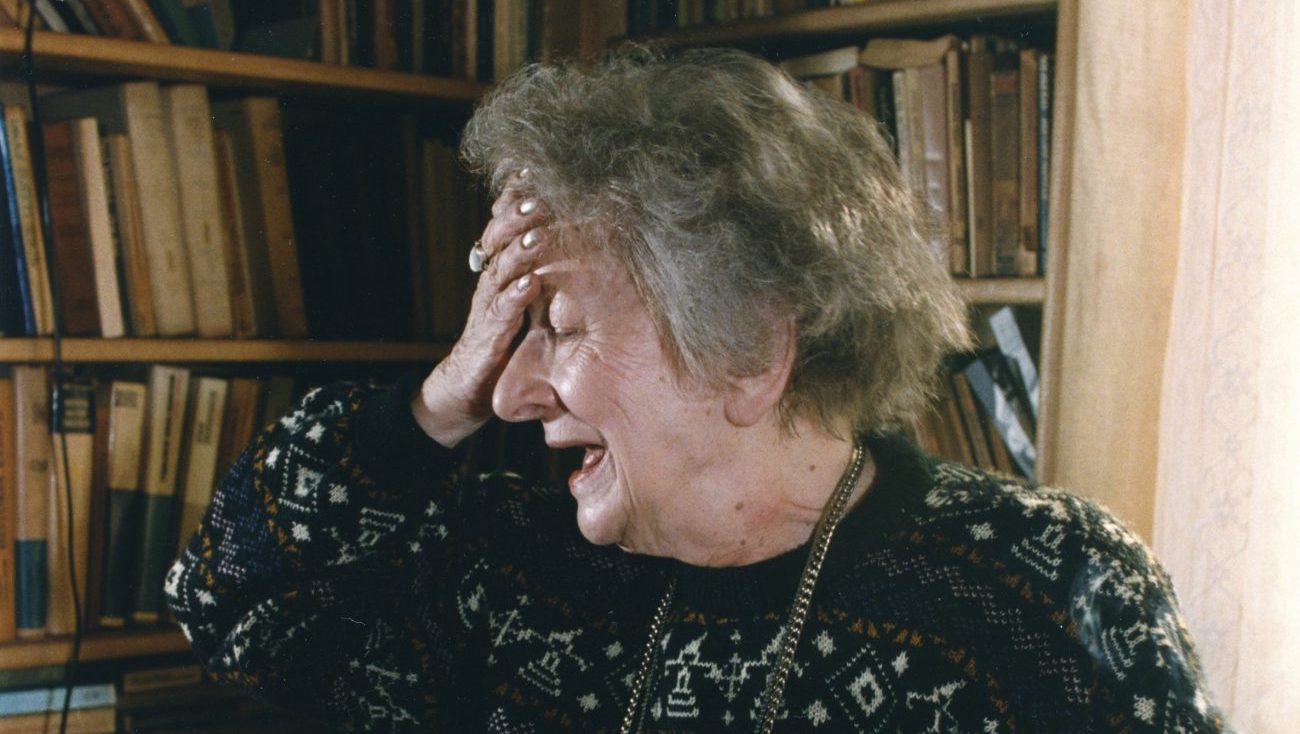

Szymborska, who died ten years ago this week, was one of the greatest European poets of the modern age, a winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1996 among a string of other literary decorations. She had little time for the ‘how-to’ books, observing that, “We hear such things appear in the United States, but we make bold to question their worth for one simple reason: wouldn’t any author who possessed a fail-proof recipe for literary success rather profit from it himself than write guidebooks for a living? Right? Right.”

This withering put-down of a lucrative genre now appears in her own collection of advice to writers, something that would have amused her greatly. Yet while How to Start Writing (And When to Stop) isn’t really a guidebook as such and doesn’t directly describe her own experiences, this

posthumous English translation of her collection of literary tips and observations merits a place on the bookshelf of every writer, from novice to veteran.

Wisława Szymborska lived through most of Poland’s turbulent 20th century and produced an astounding body of work that continues to be praised across the world. Importantly, she never lost a trait vital to being a successful writer – a strong sense of self-doubt.

She described her Nobel win as “the Stockholm tragedy”, having found the experience so overwhelming she wrote next to nothing for the next two years. When in 1996 she stood at the lectern to give her acceptance address Szymborska began in characteristic style. “They say the first sentence in any speech is always the hardest. Well, that one’s behind me now, anyway.”

Having suggested when her award was announced that two other Polish poets, Zbigniew Herbert and Tadeusz Rózewicz, might have been equal or

even more deserving recipients of the prize, she went on to express an uneasiness familiar to many writers.

“I have a feeling that the sentences to come – the third, the sixth, the tenth, and so on, up to the final line – will be just as hard, since I’m supposed to talk about poetry. I’ve said very little on the subject, next to nothing, in fact. And whenever I have said anything, I’ve always had the sneaking suspicion

that I’m not very good at it.”

This refusal to succumb to the effects of unbridled adulation despite how highly she and her work were regarded stemmed from a combination of her self-awareness and deep respect for literature. That’s what shines through all her work, and nowhere more brightly than in this entertaining and extremely useful selection of a great writer’s thoughts about the craft.

For 14 years between 1968 and 1981, Szymborska oversaw the ‘Literary Mailbox’ column in the Polish journal Zycie Literackie (Literary Life), in which she would respond anonymously with advice and opinions to short stories and poems sent in by readers, and it’s a selection of these responses that makes up How To Start Writing (And When To Stop).

We’re not party to the original submissions, but judging by this assemblage of bite-size analyses their quality varied widely and Szymborska’s occasionally sensitive, frequently cutting but always honest reactions make this a valuable book for anyone looking to improve their chances of publication or just make their writing as good as it can be.

During her years of sifting through the journal’s mailbag, Szymborska came across every kind of writer – the pretentious, the uncertain, the derivative, the timid, the vulnerable, the narcissistic – and tailored her responses accordingly.

She’s not impressed by the work of K.K. from Bytom, for example, calling

it “cliched, immature, shapeless”, but reminds them that poetry “is, was and

will always be a game. And as every child knows, all games have rules. So why do the grown-ups forget?” To O.L. from Krákow she writes, “If you lack the courage to come and talk with us about the poems you sent, why not come anyway? We welcome the timid. They generally seem to set themselves

higher standards, they are more persistent and think more deeply”.

When the submitted work was actually good she was delighted to say so. She asks Jawor from Wroclaw to “please stay in touch – we sincerely hope that you’ll keep writing”, an exhortation she also makes to Marlon from Bochnia, adding “Think about poetry, read poetry but also consider acquiring practical know-how independent of the muses’ patronage. They are hysterical, and hysterics are notoriously unreliable”.

If the submissions were terrible she was equally adept at pointing this out with admirable directness. To a prospective poet named Baska who had enclosed a note with her verse stating “My boyfriend says I’m too pretty to be a good poet. What do you think of the poems I sent?” Szymborska replies, “We think you must be really pretty”.

It’s a slim volume but the 14 years’ worth of consideration, cogitation, frustration and delight it contains will benefit both the curious reader and the writer looking for inspiration. Any book claiming to teach you how to become a successful writer is pulling your chain. Your best bet is to trust

yourself, have something to say and read writers you admire without trying to imitate them. As Szymborska tells one earnest submitter of a short story, “We remain unmoved. You borrowed your terror from Kafka, and like so many borrowed things, it was ill-used. Thank heavens the lender does not want it back.”

If some of these replies seem harsh, their roots lie in Szymborska’s deep respect for literature and abhorrence of pretension. She was a huge fan of the trashy US soap Dynasty, for example, in which she detected “motifs from Greek mythology, recycled and made palatable for a contemporary mass audience”.

What truly makes Szymborska’s book so valuable is how it submits to the joyous mystery of literary creation. It is a mystery, always will be, and the best writers will always be the ones who rather than trying to solve the mystery, embrace it instead.

As she tells B.K. from Radom. “We guess from your penmanship that you are still fairly young and have many years ahead of you. So read good poetry and read it well, tracing the countless incarnations of every word. These are, after all, the same words lying dead in dictionaries or leading a grey life in daily speech. Then why do they shine like new in poems, as if the poet had just discovered them? That’s the question, as Horace used to say.”

How to Start Writing (And When to Stop): Advice for Writers by Wisława Szymborska, translated by Clare Cavanagh, published by New Directions