When looking back on 2021 from a slightly greater distance than, well, 2021, I envisage smiling to myself and saying with tangible affection, “Ah yes, 2021, that was a pretty normal year for books.”

Depending on how things have gone in the meantime, I might even let out a little sigh because it has been a pretty normal year for books and, by jiminy, what a marvellous thing that is.

The publishing industry held itself together during 2020 despite bookshops being closed for most of it, meaning that when restrictions were lifted, and we could wander, wearing a mask, among the shelves again, it helped to create a straightforward, no-nonsense, reassuringly solid bookish 2021.

There were some brilliant books published this year, some half-decent ones and some absolute stinkers. By some, I was transported into reverie by the magical combination of prose, rhythm, simile, plot and stylistic panache. By others, I was left, after a few pages, wondering which chutney-brained nitwit had seen fit to commission something that was clearly the result of a dugong lying on a laptop, shifting its weight trying to get comfortable.

You can’t really ask for more than that from a literary year.

The literature of 2021 won’t stand out among other years, and that is its greatest achievement. The publishing industry, never exactly lightning fast to adapt to changing circumstances, could have been ravaged by the pandemic, but, unlike those of us who eschewed Joe Wicks in favour of biscuits, it emerged this year in pretty good shape.

Let’s have a rummage through the books that stood out. It was definitely a decent year for prize winners, with Damon Galgut grabbing the Booker at the third attempt, with The Promise, and David Diop scooping the International Booker with the dark, unsettling At Night All Blood is Black. Susanna Clarke picked up the women’s prize for the magical and majestic Piranesi, and Hilary Mantel added the Walter Scott Prize for historical fiction to her increasingly crowded mantelpiece with The Mirror and the Light.

The Baillie Gifford Prize, the major award for non-fiction, was won by Patrick Radden Keefe for Empire of Pain: The Secret History of the Sackler Dynasty, and the Wainwright Prize for nature writing was carried off by James Rebanks for English Pastoral.

Writing good non-fiction is harder to pull off than you might imagine. On the face of it, the story’s there and all you have to do is put it into words. Of course, it’s much more complicated than that. There are the tangents and cul-de-sacs on and into which the research leads you, the contradicting sources, the gaps you can’t seem to fill even with the most meticulous research and that’s before even trying to organise the story into a compelling narrative written well enough to keep the reader with you until the end.

Non-fiction involving personal memoir is even more difficult to get right: your family history might be hugely interesting to you and your nan, but beyond that… who cares?

In The Language of Thieves: The Story of Rotwelsch and One Family’s Secret History (Granta, £16.99), Harvard professor of English Martin Puchner takes distant memories of his Nuremberg childhood and builds on them to uncover a remarkable story of an ancient dialect spoken by central European itinerants, “people eternally on the road, escaping to nowhere,” told mainly through the contents of a family archive he’d inherited. This is a wonderfully gripping story that ventures fearlessly into some pretty dark family secrets to tell the story of a Europe you won’t find in conventional history books.

The essay collection is enjoying something of a literary renaissance and two books from mainland Europe caught the eye this year. Slavenka Drakulic’s Café Europa, a series of reflections and pieces of reportage from a fractured continent, was published in 1996 and this year, 25 years on, came Café Europa Revisited: How To Survive Post-Communism (Penguin, £14.99). The eponymous café represents the former smoky coffee shops of central Europe, now spruced up with espresso machines where the punters “complain about the corrupt elites, unfulfilled promises, loss of national identity and loss of job security – as well as the stripping away of illusions”. Having praised British cultural influence in the pre-Balkan-wars Yugoslavia, in the final chapter, My Brexit, Drakulic writes: “The British and their culture are so much a part of European identity that even when they sailed away, we had the best of them and will continue to do so. No politicians in the world can pull out their threads from the colourful woven fabric of European culture. It is just not possible.”

Jenny Erpenbeck’s collection Not a Novel (trans. Kurt Beals, Granta, £9.99) contains a range of illuminating dispatches from Europe since the 1990s, based on a life half of which was spent in a Berlin divided down the middle. These are absorbing takes on our continent tinged with wit, anger and sorrow.

This year, I also enjoyed The Lost Café Schindler (Hodder & Stoughton, £20) by Meriel Schindler, the story of her quest to find out the truth behind her late father’s extravagant claims about their family history and the Innsbruck establishment of the title, leading to a gripping delve into the Schindlers’ experiences during the last days of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and the rise of the Nazis.

My favourite non-fiction title of 2021 meets all the requirements of good narrative non-fiction outlined above. Jennifer Lucy Allan’s The Foghorn’s Lament: The Disappearing Music of the Coast (White Rabbit, £16.99) seems an unlikely choice for a non-fiction book of the year but its combination of memoir, travel and a passionate obsession that never once felt anything but authentic, makes this an exceptional book. Allan has a PhD in foghorns, yet keeps the book entirely accessible at all times despite the evident rigour of her research. There’s no navel-gazing either in this perfectly pitched, utterly beautiful book whose melancholy title belies the uplifting, joyous experience of reading it.

One fiction highlight of the year was Pushkin Press’s The Passenger by Ulrich Alexander Boschwitz (trans. Phillip Boehm, £14.99), which The New European was among the first to champion and which has gone on to become a huge bestseller. Its author drowned in the 1942 torpedoing of the MV Abosso, off the Azores, a ship taking displaced refugees to Britain from Australia.

He wrote The Passenger in the aftermath of Kristallnacht in 1938, an event that forced his protagonist, wealthy Jewish entrepreneur Otto Silbermann, to flee his home, staying on the run, zigzagging across Germany on a succession of trains to nowhere. “Even a thief on the run with his loot has a smirk on his face,” reflects Silbermann, “while all I have is fear.”

Rónán Hession’s Panenka (Bluemoose Books, £15) was another fiction highlight. It’s the story of a former footballer, remembered for a disastrous on-field failure and now troubled by terrible headaches.

Hession’s novels glow with the warmth of his sympathetic insight into the marginalised of society, the troubled and the lonely, and are among the most soul-gladdening novels in contemporary literature.

Rosa Rankin-Gee’s Dreamland (Scribner, £14.99) took seven years to write and was then launched into a pandemic. But this dystopian account of Margate in the near future has deservedly become a bestseller. Her protagonist, Chance, a teenager abused for most of her life but blessed with gargantuan strength of will and a quick-thinking intelligence, is one of the most compelling literary characters to emerge this year, in a brilliant book that has much to tell us about climate change, Britain’s class divide and even Brexit.

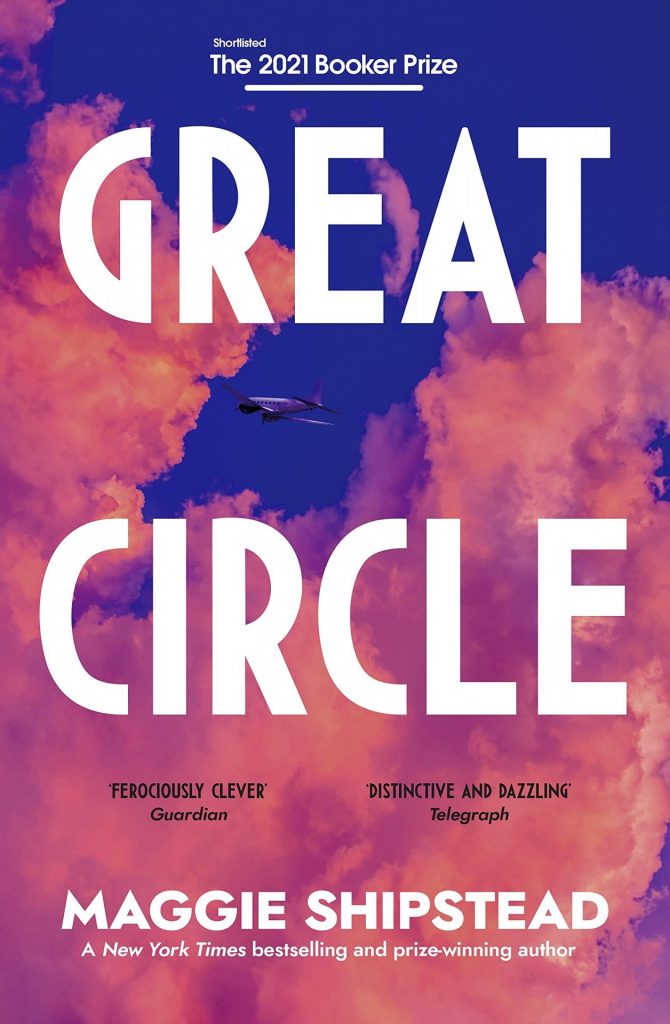

In another year Dreamland would have waltzed away with my fiction title of the year, but that accolade goes instead to another book that took seven years to write, the breathtakingly brilliant Great Circle, by Maggie Shipstead (Doubleday, £16.99). Shortlisted for the Booker, this story of a female pilot who goes missing in 1950 while attempting an all-but-impossible round-the-world flight via both poles, is epic in scale, hugely ambitious, beautifully written and pretty much flawless.

It ranges across decades and covers almost the entire globe, from Antarctica to the Aleutian Islands, creating absorbing, nuanced characters whose welfare you genuinely care about, in prose that conjures images in the reader’s mind so vivid that you almost forget you weren’t actually there and these people never existed. Great Circle is a monumental achievement. My book of the year by a long way.

And now to the Christmas break, before waiting to see what next year brings. I trust we all have our holiday reading sorted.

Mine includes some Dorothy L. Sayers and Wordsworth’s The Prelude, a book I may in the past have lied about reading, not least when it was a set text for my English literature A Level. May all your bells jingle, and see you on the other side.