When the Channel Tunnel finally opened in May 1994, it had been a project 192 years in the making. Since the turn of the 19th century, the narrowness of the English Channel (or La Manche) encouraged engineers from both Britain and France to put forward numerous designs for a permanent crossing, some credible, many not so.

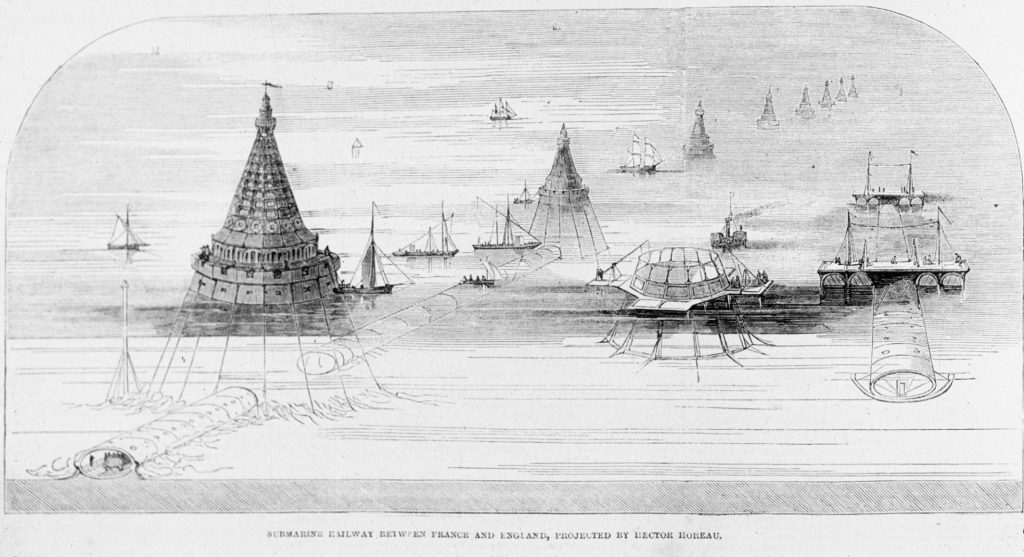

These included a sunken metal tube suspended from pagoda-like tents floating on the surface, a “submarine” train running on tracks laid on the channel bed and even a tunnel made of a frozen mixture of sawdust and water. Many bridge designs were also put forward, but the high costs of regular maintenance, coupled with the impact on what is still the world’s busiest shipping lane, rendered these impractical.

The first detailed, feasible concept for a tunnel was produced by French mining engineer Albert Mathieu-Favier, in 1802. He conceived two nine-mile tunnels meeting at an artificial island to be built in an area of shallow water in the middle of the Channel.

In the pre-railway era, the tunnels would have allowed stagecoaches to travel to and from East Wear Bay, near Folkestone, and Cap Gris-Nez, near Calais. Paved and with vaulted roofs, they would have been lit by oil lamps and ventilated by huge iron chimneys reaching through the waves above. The Varne Bank where they would meet would have been transformed into an “international town”, a harbour for ships and a place to “breathe the horses”.

Mathieu-Favier presented his plans to Napoleon Bonaparte at the Peace of Amiens, which brought an albeit temporary cessation to fighting between Spain, Great Britain and France. Napoleon in turn discussed the idea with former British foreign secretary Charles James Fox.

Although the project ultimately never made it off the drawing board due to the resumption of hostilities in 1803, both politicians were suitably impressed, but perhaps for different reasons. Fox was a leading advocate of the entente cordiale and saw the tunnel as a means of enhancing the cultural and economic ties between the two countries. Napoleon, it seems, saw the benefits of the tunnel in military terms, as part of wider plans for an invasion of Britain.

Mathieu-Favier’s proposal was not only the first technically viable one but was also the first to show that, throughout its lengthy gestation, the tunnel would be driven as much by complex politics as by economic and technical criteria. It was a mirror of European history, in particular the fluctuating relationship between Britain and France.

Interest in a tunnel was kept alive by the railway boom of the mid-1800s and the efforts of another Frenchman, Aimé Thomé de Gamond, who conducted a series of surveys charting the geological makeup of the channel’s seabed. He received approval for a plan from both Napoléon III and Queen Victoria. However, the Orsini Affair, an attempt to assassinate the French president by an Italian nationalist who had travelled from Britain, increased fears of a French invasion. The tunnel was mothballed again.

Commercial motivations rose to the fore in the mid-1800s. Edward Watkin, the so-called “Railway King”, controlled rail lines from Dover to London, through the Midlands to the north-west of England. He saw the tunnel as a way of connecting his empire to the European rail system, envisaging direct journeys from Liverpool and Manchester to Paris.

In 1880, his company began digging towards France from Shakespeare’s Cliff while a French company began work in the opposite direction. As they toiled underground, above them Anglo-French relations were deteriorating once more.

Despite plans to install a portcullis over the entrance and mine the tunnel so it could be blown up in the event of attack, parliament ordered Watkin to cease his endeavours in 1882. The tunnels on both sides had reached about a mile in length.

Resistance was also motivated by a desire to preserve Britain’s status as a sovereign island. Lord Randolph Churchill, a leading opponent of the tunnel, made this clear in a Commons debate on the topic in 1889 when he argued that “the reputation of England has hitherto depended upon her being, as it were, virgo intacta.”

However, it was the security argument that would be repeatedly deployed over the next 70 years, anxieties that were repeatedly whipped up by British newspaper editorials and cartoons showing Britain, defences down, being overrun by “French pygmies” or armies of frogs in battle uniform emerging from the tunnel.

It might have carried emotional weight but railway historian Christian Wolmar says it was never a realistic prospect. “Anyone with the slightest bit of military knowledge would realise that an army marching 50 kilometres through a tunnel and emerging at the other end would have been a sitting duck.”

These concerns were effectively turned on their head during the first world war. With the British and French now fighting alongside each other, the channel became a huge impediment to their strategic operations. Supplies had to be unloaded from trains at British ports then reloaded in France. Even when boats were built to carry rail wagons, the cross-Channel journey was treacherous and slow because of the constant threat from U-boats.

Marshal Ferdinand Foch, the French general who became supreme allied commander on the Western Front in 1918, claimed a tunnel might have prevented the conflict altogether, or at least delivered victory for his forces two years earlier than it came. Yet still the threat of invasion loomed large in British thinking about the project.

In 1924, the new Labour prime minister, Ramsay MacDonald, referred the issue to the Imperial Defence Committee, which included four former prime ministers: Asquith, Baldwin, Balfour and Lloyd-George. Despite support from British businesses and some 300 MPs, they emphatically rejected the idea.

A future prime minister disagreed. Winston Churchill, who had been minister of munitions at the end of the first world war, was all too aware of the benefits. Unlike his father, he became a fervent advocate for the tunnel, arguing that the “ponderous and overwhelming resistance has always seemed a mystery.”

By 1955, defence concerns were finally allayed. When asked whether strategic considerations continued to prevent construction of a tunnel, Harold Macmillan, then minister of defence, replied “scarcely at all”. Eleven years later, British PM Harold Wilson and his French counterpart Georges Pompidou announced plans for a £170m tunnel.

Still, hurdles existed. The project was subject to the conflicting priorities of two governments, two state railway companies and various contract teams. The road lobby, port and shipping firms, trades unions and environmental groups all also exerted pressure on the process. Civil unrest in France in May 1968, the death in office of Pompidou, by then French president, in 1974, and the uncertainty caused by two British general elections in the same year all added to the inertia.

By 1975, the year the tunnel was supposed to have opened, the cost had risen to £850m. In a precursor to HS2, the recently elected Labour government, clinging to power by a wafer-thin majority, balked at the cost. They unilaterally called time on the project in January, on the very day that The Mole, a giant 226-tonne excavating machine, began to cut into the Dover chalk.

“I think in a way it shows that we have a lack of conviction about our attempts to improve our infrastructure,” says Wolmar. “We can embark on things, but don’t see them through.”

Within a decade, the project had been resurrected; the Conservative government of Margaret Thatcher and the Socialist government of François Mitterrand finding common economic cause. In Thatcher’s case, support also had a personal dimension. According to Nicholas Ridley, transport secretary at the time, she wanted to build a “permanent reminder of her premiership”.

The tunnel was officially opened by the Queen and Mitterrand at ceremonies in Folkestone and Calais on May 6, 1994. The first passengers made the journey in November 1994. It had taken some 13,000 workers six years to build the 31.4-mile tunnel. The 23.5 miles that run under the Channel remains the longest undersea tunnel in the world.

The age-old security concerns, the fear of what horrors the tunnel might bring to Britain’s shores, lingered. Eurostar passengers had to undergo airline-style security checks; onerous requirements deemed unnecessary on trains travelling through tunnels between countries on the continent. It limited the ease with which people could use the route. The Channel remained a barrier of sorts.

“What we never had was trains from, say, Canterbury to Calais, that is local trains that would have allowed people to commute, like people do from Brussels to Lille,” says Wolmar. “Instead, we have the Eurostar, which gets us over very quickly, but it doesn’t create any feeling that we are closer to Europe than we were when we only took a plane.”

Although the tunnel finally created a physical link between Britain and its European neighbours, it failed to strengthen cultural links, a missed opportunity to cement Britain’s place in Europe, Wolmar argues. “Brexit was the ultimate expression of the fact that the tunnel had failed.”