Manchester, 1992. The city is stirring, but something is coming that will help shake it fully awake. Something that will paint in bold colours after the drabness of the 1970s and ’80s; something that will speed up football’s rehabilitative ride from decline and danger to national obsession. Something that will broaden British horizons, making the nation more cosmopolitan and more confident. Something that will – temporarily, it turns out – bring us closer to Europe.

But first, it had to change Manchester. Though contemporary “I love the 1990s” telly shows might indicate otherwise, that era’s bucket hat-and-flares Madchester Rave On vibe had not reached everyone in the city. Most pubs were still smoky and swirly-carpeted. Footballers, mulleted and stonewashed. Wine bars, if you fancied wining, had a strict dress code of no trainers, baseball caps or jeans.

In Manchester itself, there were several cool places that pushed towards the new: New Order’s clubbing mecca The Haçienda, of course; also its spin-off Dry bar, plus vast dancehall The Ritz and live music centre Band on the Wall. There was the Cornerhouse arts centre for those who liked films more taxing than Lethal Weapon 3; Affleck’s Palace for second-hand clothes or band T-shirts. Still, going into town – the city centre – was something that only certain people wanted to do.

Manchester was seen as grubby by locals with money (footballers, also Coronation Street actors and successful small-business owners). Such people tended to live and socialise in Wilmslow, Alderley Edge and Prestbury, small towns south of the city that boasted large Tudorbethan mansions, chichi shoe shops and Italian restaurants where the waiters would present every lady diner with a slim red rose (wrapped in plastic). There, late-night shenanigans consisted of hotel nightclubs with tiny light-up dance floors, as opposed to Manchester’s messy, packed, sweaty-walled fun halls.

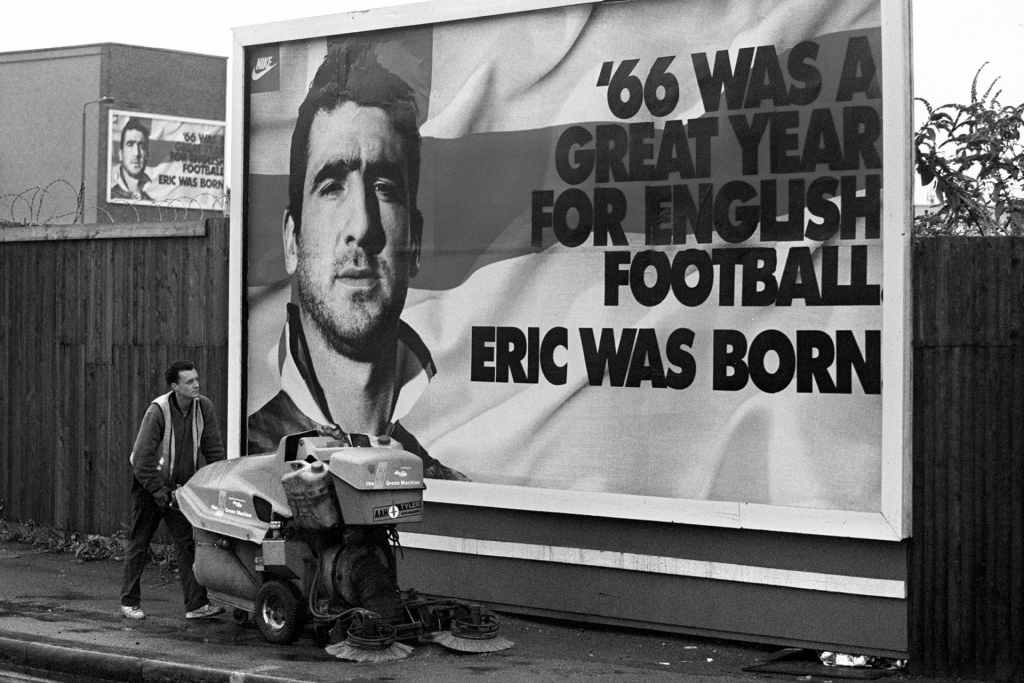

Manchester was building an international reputation for amazing bands and cool clubs, for alternative culture and interesting people, for a defiant vibe, a “so what” attitude, but in 1992, only a certain type of person was drawn to the city. And definitely only a certain type of footballer. Most teams outside of London were made up of English, Welsh and Scottish players, with perhaps one or two international stars, who were seen as quixotic, flaky and liable to tantrum when playing in rain and mud. And Manchester had plenty of rain and mud. Which brings us to November 27 of that year. In the week that Whitney Houston started her 10-week run at No 1 with I Will Always Love You, a 26-year-old Frenchman arrived at Old Trafford, home of Manchester United FC. Eric Cantona, the talented forward who’d been instrumental in Leeds winning the league the season before, had been sold by that club to United for £1.2m. It was an unexpected move. Leeds fans were distraught – “shattered”, said one to a reporter – and commentators dubious. “His temperament has, at times, led to trouble with the authorities,” noted a BBC presenter, with considerable understatement. (The presenter, too, sported a mullet.)

Cantona had always cut a swathe with his football, but his confrontational attitude had brought him up against various managers, including the French national coach (he insulted him on TV) and Raymond Goethals at Marseille. When, in 1991, Cantona was banned for a month by the French Football Federation for throwing the ball at a referee, he went up to each member of the hearing committee and called them an idiot. Cantona was seen as supremely gifted, but a mouthy rebel. A black sheep, a troublemaker. He was made for Manchester.

“Manchester’s got this rebellious history,” says Saltz Anderson, lead singer of former Factory Records band Jazz Defektors, now a film-maker, social media entrepreneur and man about town, who became friends with Cantona during the Frenchman’s time in the city. “It’s about the people, much more than London. There’s a socialist mentality and Cantona was just perfect for it.”

Anderson met Cantona via Mick Hucknall, lead singer with Simply Red and huge United fan. “I introduced myself and then the next time he saw me, he came up and said: ‘I remember you’. He’s different to other footballers. It might sound mad, because he’s known for being cocky, but he’s humble. He talks to people on the same level.” Anderson relates this to Cantona’s growing up in Marseille, a city that shares several characteristics with Manchester. A mixed heritage, a love of football, a for-the-people approach, an anti-authoritarian cheek. “Liverpool’s got the same thing,” acknowledges Anderson, “but culturally, Manchester’s got a better mixture.”

Cantona loved culture, and he loved Manchester from the moment he arrived. First, of course, because of his job. Alex Ferguson, Manchester United’s Glaswegian manager, shared many of Cantona’s characteristics: he was fiery, prone to outbursts of anger, a passionate lover of football and a man’s man. Ferguson slotted the Frenchman into the team, knowing he would fit with United’s hard men (Steve Bruce, Denis Irwin, Gary Pallister, Paul Ince, Mark Hughes: you wouldn’t mess), and that he would also be creative, like the team’s mercurial young wingers, Lee Sharpe and Ryan Giggs. He let Cantona be who he was: both tough and magical. Ferguson was the first, and, as it turned out, the only manager who could actually manage Eric Cantona.

So, the football side was good. But so, too, for Cantona, was the city.

“Eric and I, we often talk of Manchester,” says Claude Boli, scientific director of the French National Sports Museum and author of The King and I, about Cantona’s time in the city. “All the time. We were happy there, we adore that town. First: everyone is passionate about football. United or City, City or United, everyone is passionate. And second, Manchester is a city of music.”

Boli, a long-time friend of Cantona, came to Manchester a few years before 1992, to accompany his wife, who works in African textiles (Manchester is one of only two cities in Europe that made the textiles Madame Boli required). Boli had known Cantona for years, “when he was just ordinary, not King Eric. Not even a prince”. He and Cantona had struck up a friendship when Cantona was a teenager at Auxerre’s academy, through Boli’s brothers, who were also at the club.

In Manchester, Cantona and Boli spent a lot of time together. (In fact, Boli – who doesn’t speak English as well as Cantona, and remained quiet in conversation – would often be mistaken for another United player, the taciturn Andrew Cole.) And what did they do? They went to gigs. Both Boli and Cantona had loved English music for a long time, mostly tuneful post-punk – Tears for Fears, Simple Minds – what they called “new wave”. Boli had enrolled as a PhD student at Manchester University, and the university’s student union was a great place for live performances. Cantona and Boli would go along – Boli with his student ID, Cantona with nothing of the sort – and when required to show his student card, Cantona would just say “Sorry” and he would be let in.

They saw various Acid Jazz bands, remembers Boli, also Everything But The Girl and Massive Attack, “so many bands”, he says. Though they went occasionally to the Haçienda, they weren’t regulars: the space was too big, the crowd too messy. They preferred Band on the Wall and the Boardwalk: smaller clubs, more dedicated to live shows. Cantona loved local band The Stone Roses and, when they came along in 1993, Oasis – the latter not just for the music: he liked the argumentative rivalry of Liam and Noel.

Outside of gigs, the two Frenchmen’s regular hang-outs were the Café Renoir in Fallowfield, just south of the centre, and the Cornerhouse, the film and arts centre near Oxford Road station. (Cantona was also a member of the Portico Library, the independent library founded in 1806.) Being French, they were more interested in a quiet drink than getting mangled, plus they loved non-mainstream films. Anderson remembers going to see Il Postino with Cantona at the Cornerhouse and discussing it in detail afterwards.

Tim Sheehan, who managed the Cornerhouse’s foyer bookshop at the time, recalls Cantona coming in. “I was used to seeing visiting celebrities because of the Cornerhouse programming and the BBC studios over the road, but he was different,” he says. “He came strutting across the road dressed in a trendy, brightly coloured G-Force cardigan, his chin held high and his back ramrod straight, like a ballet dancer. I’d never witnessed such charisma in the flesh before. And I’m a lifelong Liverpool supporter.”

Ah yes, the Cantona walk. Mancunians have always had a swagger: a bowl to the stride, a jut to the chin, coat zipped to the top, indoors and out. Cantona, with his own special way of moving – shoulders back, chest out, collar aloft – didn’t quite chime with the local strut, but the attitude was the same. And he and Boli walked everywhere. It’s what Boli remembers most about their time. Cantona would come to Boli’s house near Maine Road, City’s then-home, and they would set off. They had favoured routes. Sometimes Cantona would park at Debenhams, in the city centre, and they would walk to Oldham Street and on to Castlefield. Often they walked all the way out of town through Fallowfield to Withington.

They would, of course, encounter all sorts of people on the way; some fans, some not. Once, when they were in HMV on Market Street, looking at the records, two lads came in and squared up to them, announcing that United were shit. Cantona said: “You are City supporters?” (they were), and indicated Boli. “So is he.” Which Boli was, from living near Maine Road. The situation was defused. There were other encounters. Anderson tells a tale of Cantona in London, causing a near pile-up by walking across Kensington High Street. “The traffic just stopped, it parted like the Red Sea,” he says. “Though me and my then-girlfriend were nearly knocked down even though we were just behind him. Because we weren’t him.”

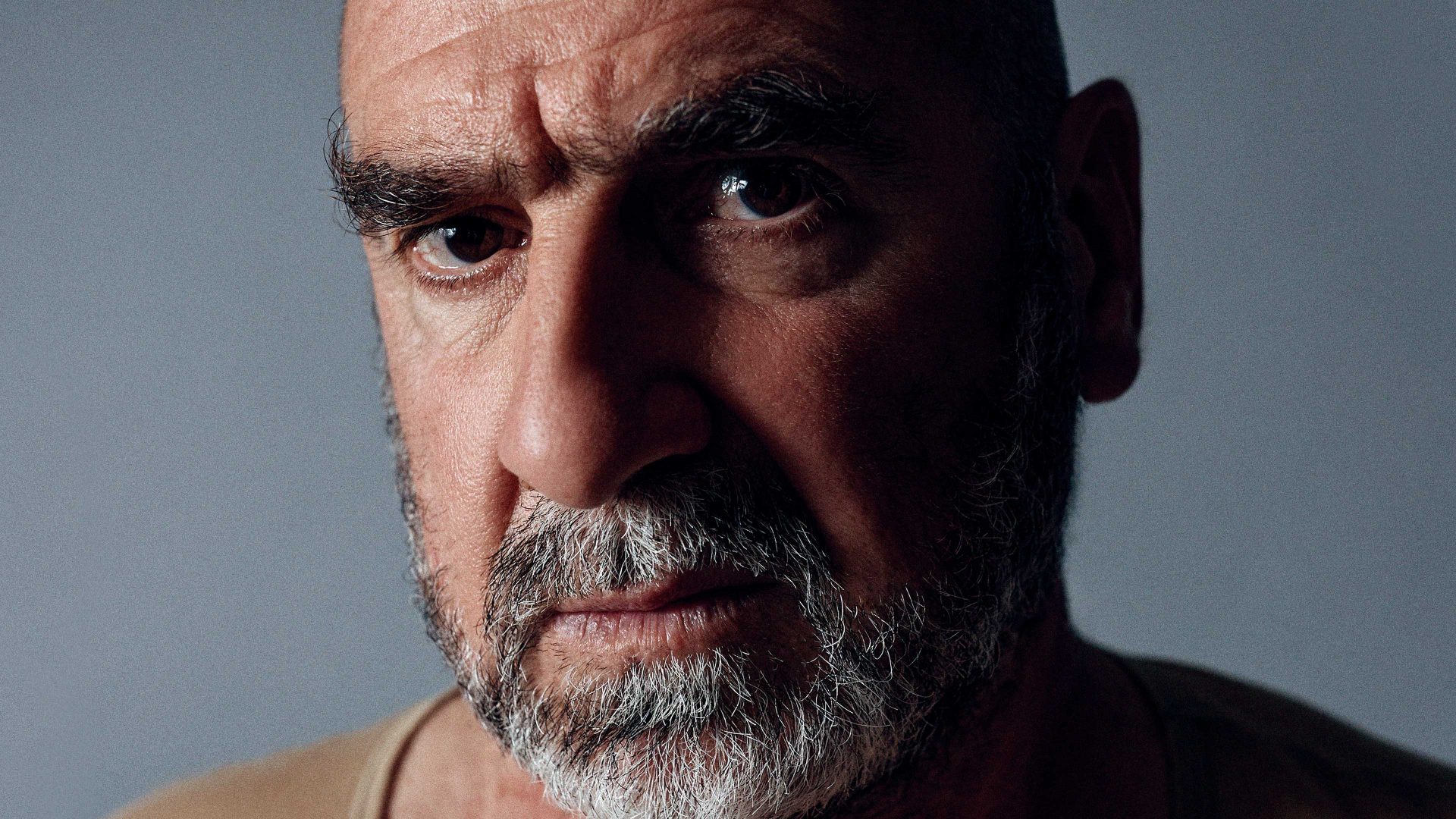

It’s a religious analogy and for many Mancunians – mostly men, you note – Cantona was akin to a god. It wasn’t just his footballing prowess, though that helped, and it wasn’t just his wide range of interests (as a fan noted at the time, “he’s not your average boring footballer: he likes poetry and art”). It was the very essence of Cantona: his masculine charisma, his particular mixture of arrogance and humility. He was cock of the walk on the football pitch; so tough that not even Vinnie Jones could faze him. He carried himself with pride. He was exotic: an art-loving European sophisticate in a rainy industrial city.

But, at the same time, he wasn’t remote. He lived in an ordinary four-bedroom house in Worsley, a non-glamorous area near Salford. He drove an everyday car. Anderson recalls him turning up at a game of the Moss Side football team that Anderson played in, as a supporter (the game was ruined, the referee had to abandon it). He always spoke to fans, he was loyal to the city and its people.

Pete Boyle, a United fan from the age of four, first met Cantona in March 1994 at the Peveril of the Peak pub. Boyle was known for creating the songs and chants for United supporters to sing at Old Trafford, and he was recording an album in a room above the pub when the manageress, Nancy, called him down. There was Cantona, his hero, playing table football with Boli. Boyle could barely speak. Cantona made him relax, and they have remained friends to this day. Boyle’s 1995 compilation Cantona: The Album got 10 out of 10 in the NME, more than the big albums of that year – Oasis’s What’s The Story…, Blur’s The Great Escape and Pulp’s Different Class.)

The combination of Cantona and music was a potent one, and enjoyed by more than just Mancunians. Londoner Chris Abbot and his brother Tim, MD of Oasis’s record label, came up with a daft rave track, Ooh! Aah! Cantona, in 1996. It reached No 11 in the charts and Abbot found himself on Top of the Pops with a Cantona lookalike many people thought was the real thing.

“It was mad, but it was the time, wasn’t it?” he says now. Without today’s restrictive surveillance of mobile phones and ever-present PRs, footballers and fans could bump into each other. And there was a silliness in the air in the mid-90s, a recklessness that propelled top-of-the-head ideas into the mainstream, via an up-for-a-laugh media, or simply through the idea-haver’s force of personality.

Perhaps it was that recklessness, plus the proximity of fan and footballer, that fed into Cantona’s infamous kung-fu kick on Matthew Simmons, a Crystal Palace supporter, in January 1995, at a United away match at Selhurst Park. Simmons had run down to the pitch to insult Cantona, who’d been given a red card and was walking off. Cantona launched himself at Simmons feet first, over the barrier, and sent him flying. It caused an absolute sensation. The media went wild, and drove straight up to Manchester. Anderson and Boli remember the next day clearly: despite the press furore, Cantona told them he fancied going to the Cornerhouse, so they all met there. “I was ducking like mad, there were so many paparazzi,” recalls Anderson. “But Eric wasn’t bothered. He just strolled across, like he always did, chest out.” Boli says the same: “He believed he had done nothing wrong, so he was at peace.” (The FA didn’t agree: Cantona was fined, banned from playing for several months and spent his community service teaching youngsters football.)

Cantona’s perfectly timed assault, plus his reaction to the press (it was then that he came up with his famous seagulls/sardines/trawler quote), somehow catapulted him straight up on to the moral high ground. Simmons had told him to “fuck off back to France”, and Cantona, according to Cantona, had reacted appropriately. The incident turned him from Mancunian hero into Mancunian icon. Even those who knew nothing about football knew Cantona had kicked a man that he called “the hooligan”, and followed that up with a poetic declaration to the press. The most right-on, football-hating liberal could understand that one.

And for those who did love the game, it was during the season after the kung-fu palaver when Cantona left his real mark. United won the double (the league and the FA Cup), the first team ever to do so twice, a huge achievement. Cantona had already been the extra ingredient that meant the team finished top of the league in 1992-93, and 93-94. Pre-Cantona, it had been 15 years since the team had won anything at all. Cantona was the difference. If Fergie was United’s general, Cantona was his spirit animal. It was Cantona who led the team into battle, physically and spiritually; a battle that they knew they would win, because Eric was there.

If that sounds mythic, then that’s the point. Manchester has always been about the myth. A city full of writers who write about the city; a place that, given the choice between the legend and the truth, will always print the legend. We can list facts and stats, but they’re not why Cantona and Manchester worked so well. Cantona believed in his own epic tale, his particular personal heroic legend, and so does Manchester. The 1990s were a time when Manchester designed its own story arc, danced into the spotlight; built on The Smiths and Joy Division, it careered from acid house into Britpop, forced its way into becoming the talking point of national culture. It became an international sensation, without losing its specific, disruptive, proud local identity.

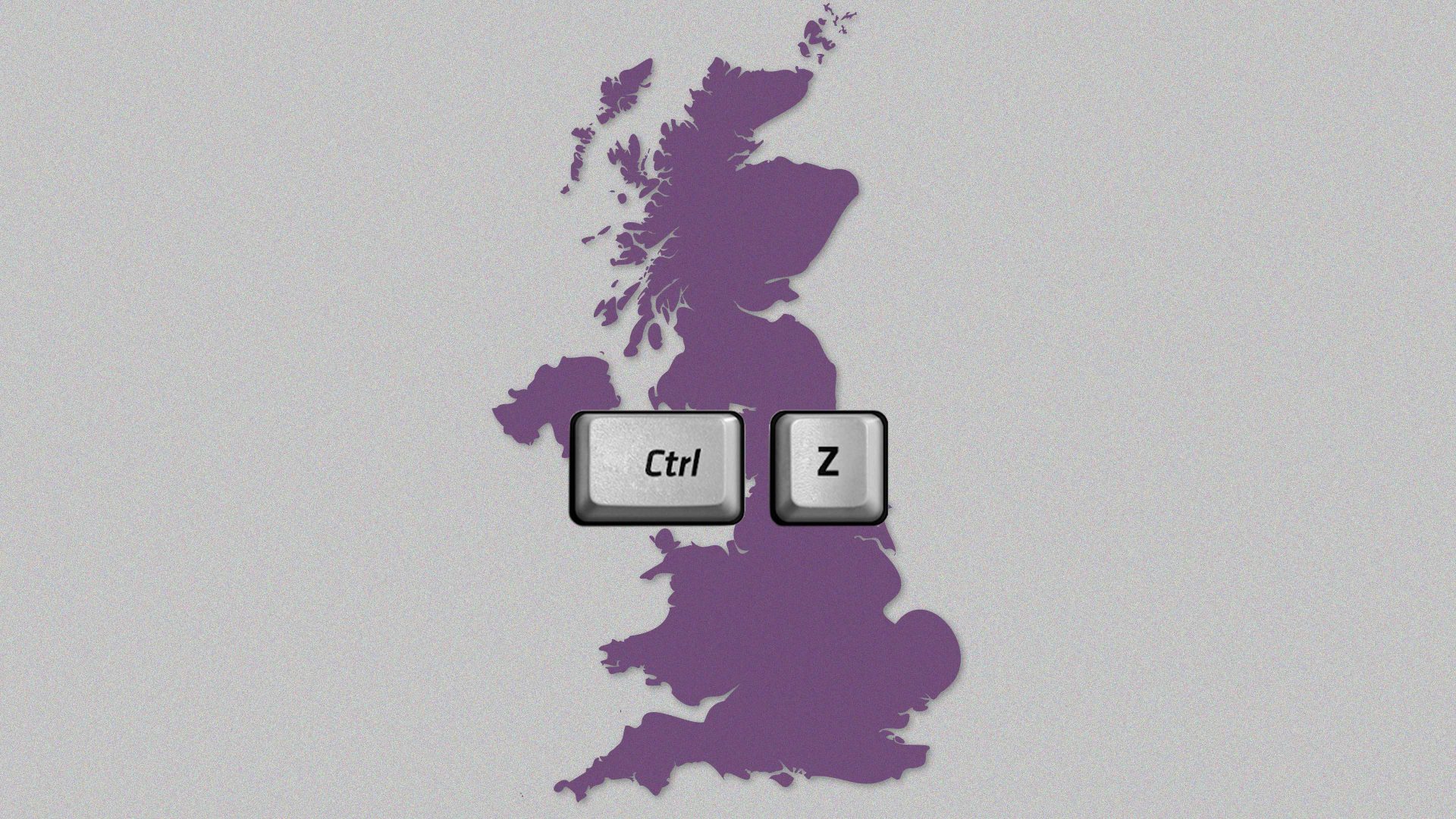

And Cantona did the same, but with football. His presence on the pitch changed the way England thought about foreign players; suddenly they weren’t namby-pamby ponces, individualists who could never be truly part of the team, but vital, totemic, inspirational leaders. Frenchman Cantona was completely United, in the same way that his compatriot Thierry Henry, a few years later, was completely Arsenal. Plus he came to Manchester at the height of his powers. After Cantona, English clubs began to look to Europe for players (Bergkamp to Arsenal, Zola to Chelsea, Ginola to Newcastle); which naturally led to clubs looking to Europe for managers. Gradually the Premier League was transformed from a two-feet-studs-up-man-up little Englander drinking club into an international talent showcase. Cantona was the catalyst.

And, while we’re talking myth, there’s something more to say. Whoever you talk to about Cantona, whether fan, friend or foe, they all swoon a little about him. They struggle for words, they can’t capture his significance; Cantona’s specialness, the quality that made him different. Of course, he was foreign and, therefore, unusual: but, at the time, the French were seen as ridiculous, cowardly, up themselves. Cantona was far from a coward; and he somehow transformed ridiculousness into something heroic. The football, the anger, the arrogance, the education, the way with people, the collar, the walk, the talk. All individual parts that added up to something more: a charisma, a je ne sais quoi. It’s a rare talent to be able to rise to an occasion, to peak exactly at the moment required.

By 1997, when he made the decision to retire (at the peak of his powers! So cool), Cantona was loved not only by United fans, but by some City supporters as well. Even today, die-hard blues will proudly show you photographs of themselves next to Cantona. He has become, in a way, as much a Mancunian hero as the Gallagher brothers.

And if you don’t believe me, have a look at the video for Once, Liam Gallagher’s recent single. In it, Cantona plays a drunken king, lurching through a palatial mansion, full of yearning for his triumphant youth. Liam plays his chauffeur. When they made the video, reports Liam, Cantona didn’t want any money to appear; he paid for his own flight, his own hotel, even his own wine. King Eric turned up, did the job with passion, professionalism, poetry and style, and left when the job was done. Liam loved him.