Tracey Emin is a passionate Remainer. “I am ridiculously pro-Europe. I see Britain leaving Europe as one of the most hideous, heinous things that any nation could have done,” the artist tells me over a pot of green tea upstairs at the Palazzo Strozzi in Florence, where over 60 of her works have just been installed in a new show called Sex and Solitude.

Ever the Europhile, Emin is delighted to be in Italy, even more so because despite her pronounced international acclaim, this is the 62-year-old artist’s first institutional solo show in the country. It’s a privilege that she can enjoy only on account of her international status, and very much in spite of the economic and cultural fallout of Brexit.

“You’ve got to be a really big artist now to show in Europe because of all the taxes and the costs,” says Emin, who spends part of her time working from a studio in the South of France.

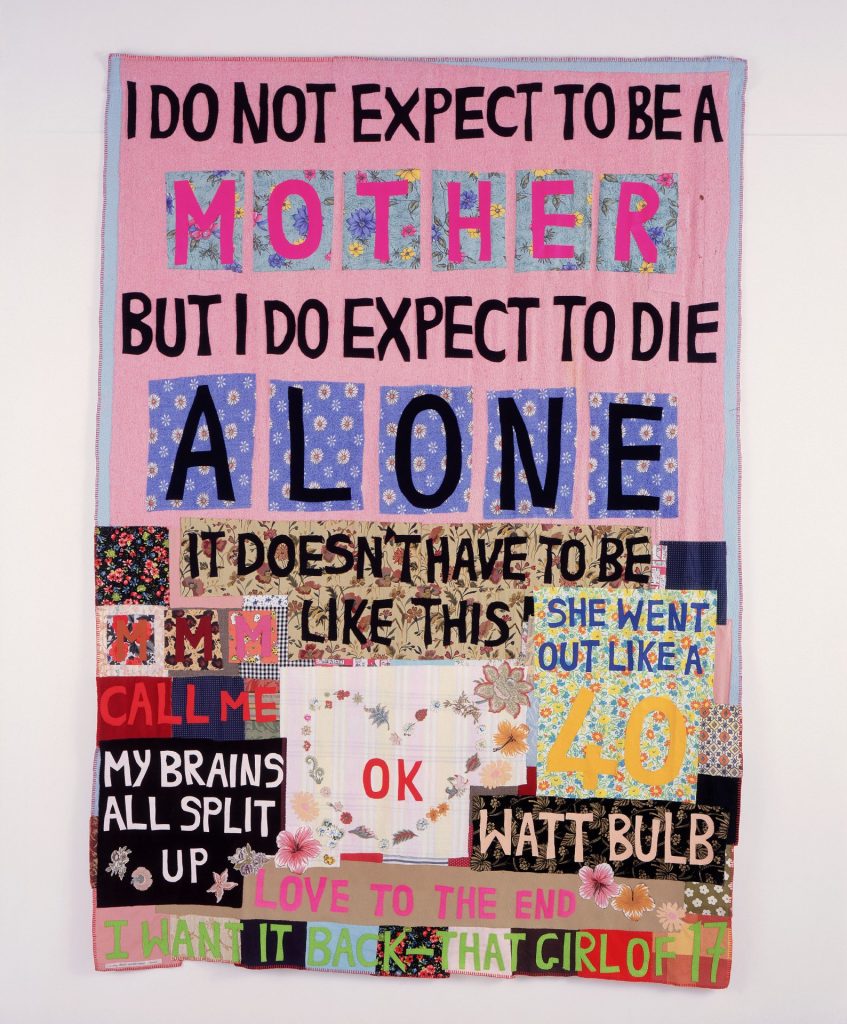

The show spans three decades of Emin’s career and represents her restless creative experiments in drawing, painting, embroidery, print-making and more recently, bronze sculpting.

A discreet blue neon sign bearing the exhibition title interrupts the Renaissance façade of the Palazzo Strozzi, and once over the threshold, visitors are confronted with an immense bronze sculpture of a truncated body, bent over on all fours, haunches raised in agony, ecstasy, or both.

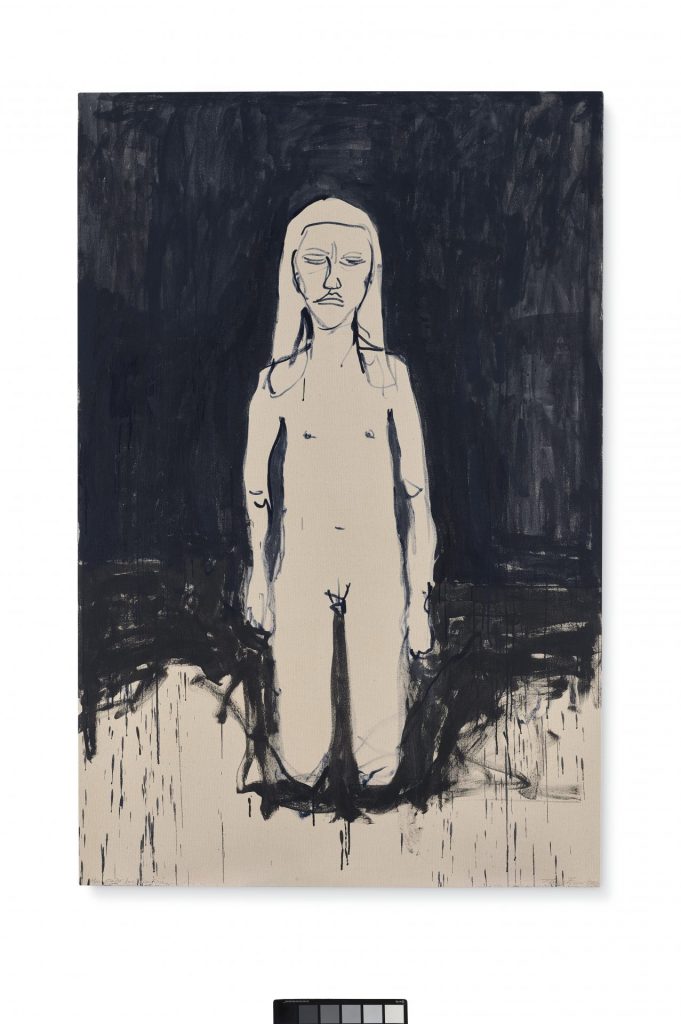

As to be expected from the title, sex is everywhere: poems to past lovers pulse in vivid neon writing (one of the artist’s favourite mediums since the 1990s) and entanglements of embracing bodies are rendered in large, dripping paintings, or small, amorphous sculptures, fretfully cast in bronze.

“For a long time, sex was my way of exploring the world. Whether good or bad, it was sexual energy that drove me,” Emin says. Both the “good” and “bad” course through the pieces in the show: titles of the works range from reveries of tenderness and erotic satisfaction, to expressions of loneliness, violent trauma and the frustrations of desire and its aftermath.

The artist has always been candid about her formative experiences of rape and abortion, and spectres of both haunt her images, sometimes appearing in paintings as unresolved forms inside bodies, or sometimes as the traumatic driver for key works. Included in the Florence show is a reconstruction of an installation piece from 1996, called Exorcism of the Last Painting I Ever Made, which Emin performed in a studio space within a museum in Stockholm. Sequestering herself for the duration of one menstrual cycle, she worked, naked, and under the public gaze of the museum audience, producing paintings inspired by the canon of male modernist greats from Picasso to Yves Klein.

The process was intended to “exorcise” her relationship to painting, which she had abandoned altogether for six years during a period of intense self-loathing after a traumatic abortion. Emin turned the tables on the idea of the conventional, passive female nude in the studio who waits to be translated to canvas in an expression of the male artist’s genius. Instead, she presented herself as both artist and subject while also addressing aspects of female sexuality such as menstruation and abortion, which are almost unanimously absent from the walls of the museum.

In Emin’s hands, sex, for better or for worse, becomes the creative fuel that was once the preserve and privilege of male artist (think of the priapic Picasso and his many conquests, or Renoir, who is alleged to have said “I paint with my prick”).

Now a seminal work of feminist art, it is one of the most conceptually compelling pieces in the show; its considered critique of gender bias in art history contrasting with the majority of the recent paintings on display, which Emin insists are produced in moments of unfiltered creative flow and are not premeditated or contrived with any narrative.

I offer my thoughts on readings of her painted bodies as disfigured by pain or desire, but she doesn’t want to be pinned down by interpretations.

“I don’t think about that when I’m painting,” she volleys back at me, “I’m just painting.”

Close-knit creative collaborator and studio director Harry Weller assists in these painting sessions, often in the small hours of the morning, spinning the large canvases around on their axes as paint drips, and sprawls. It’s from these seemingly automatic marks that images and ideas emerge as a starting point to develop, with titles only given at the end of the process.

The show takes the viewer on a trajectory of bodily vitality to bodily morbidity, we pass from one room showing a looped video of monoprints of a woman with legs spread, pleasuring herself (Those Who Suffer Love), to a quiet suite of paintings in ghostly pastel blues produced after Emin’s bladder cancer diagnosis in 2020, during a time of multiple endings, including the death of her much-loved cat and leaving her east London home.

Elsewhere, crimson acrylic paint flows across surfaces as if from an open wound, and painted gestures to the stoma bag and tube that Emin now permanently wears after her cancer surgery are frequent.

It’s this attention to suffering and mortality that finds certain parallels with the historical art heritage of Florence, where paintings of the wounded broken body of Christian iconography are never far away. Around the corner in the Dominican church of Santa Maria Novella, a life-size depiction of a crucified Christ oozes with blood from a wound in his side. In one room of the show, these connections are made explicit in a series of bronze crucifixions of an unexpectedly female body, patinated in white. In another work in the same room, made in Emin’s trademark applique style, the stitched words compare falling in love and sexual ecstasy to a type of crucifixion.

Although the artist’s most explicit artistic homages have been to the expressionists Egon Schiele and Edvard Munch, Emin tells me how she would spend time studying the collection of Italian Renaissance paintings at the National Gallery in London when she was a student at the Royal College of Art, and dare to imagine her works on the walls alongside them.

Seeing her works hanging in the Palazzo Strozzi, a building whose history sits in the very cradle of Italian Renaissance art, and history feels like a satisfying culmination of those early ambitions and a way of inserting herself into a long tradition of painting about the human condition.

“You name it, it’s here, from Giotto to Fra Angelico, and then I’m here, I’m in the centre of it, and I’m a woman making this work about much the same kind of things really, so it all makes sense,” she says.

For curator and Palazzo Strozzi director Arturo Galansino, Emin’s ability to resonate with contemporary audiences defines her status as what he terms “one of the world’s most important contemporary artists”.

He says: “We can identify ourselves in her pain, her sorrow, her strength. In Italy, and particularly here in Florence, there’s a heightened sense of tradition, and we want to show our audiences that contemporary art is not a different, distant world.”

I was interested in how Emin would be received by a potentially more conservative Italian public, less acclimatised to Emin’s visceral themes.

“I think Florentines are intellectual, I think they understand that it’s all wrapped up in emotional content,” she says.

She is visibly delighted to be showing in Italy, but like many of her generation who wished to remain in Europe, Emin is also doleful for a younger generation of Britons with less freedom to explore the world beyond British borders since Brexit. “Young people used to move around and experience life, they can’t do that any more,” she says. She sees the impact also extending to arts education in the UK, with an art school culture that is becoming “more insular and less connected”.

The artist also sees the current conflict in Ukraine and the encroaching military mobilisation of Europe as a once unthinkable result of the fateful referendum.

“When I was on Newsnight [in 2016], talking about why I thought Brexit was bad, I said it would be the beginning of an outbreak of war in central Europe. People laughed at me.”

It’s refreshing to see the artist through the eyes of the Italians. Familiar to British audiences as the reliably outré provocateur of the 1990s Young British Art movement turned Dame of the British Empire, here in Florence the complexity, legacy and nuance of Emin’s work coalesces.

Offsite, in a tiny velvet-upholstered cinema room at the Palazzo Gucci, an artfully curated selection of video works run on a loop in the intimate nine-seater cinema, providing a contextual counterpoint to the Palazzo Strozzi exhibition.

Among them is Emin’s 1998 video, Riding for a Fall, which unexpectedly made me overflow with nostalgia. Shot on Super 8 film, Emin subverts the macho cowboy archetype as she rides a pony on the beach in her home town of Margate, full of swagger, eyeing the camera seductively, Stetson piqued, and with her shirt open to reveal her bra.

“Go ahead and have your fun girl… you’re riding for a fall” drawls Delroy Wilson on his 1977 reggae track, played over the top. It is raw and wry, and sexy and melancholy and crackles with soul, but somehow feels very new, or at least ahead of its time.

Emin’s work may no longer have the propensity to shock as it once did, three decades ago when she made tabloid headlines with her 1999 Turner Prize-nominated installation My Bed, which presented the remnants of a depressive episode after the end of an affair, complete with soiled underwear, empty vodka bottles and condoms. She acknowledges how the reception of her work has changed but insists on how necessary her consistent themes remain, from exploring authentic female sexual desire, to testimonies of trauma, abortion and disease.

“People need to know what women are thinking,” she says, “if only because they are 50% of the population.”

She sees her work and its inclusion in big art institutions such as the Palazzo Strozzi as a way of legitimising and normalising expressions of female experience that have been shrouded in taboo.

Recent punitive legal measures controlling women’s reproductive freedoms, such as the overturning of Roe v Wade in the United States, are also reflective of a broader contemporary relevance for the topics Emin tackles.

“People used to say I was moaning, but let me moan about these things in Texas and see what happens,” she says.

Tracey Emin: Sex And Solitude is at Palazzo Strozzi, Florence, until July 20