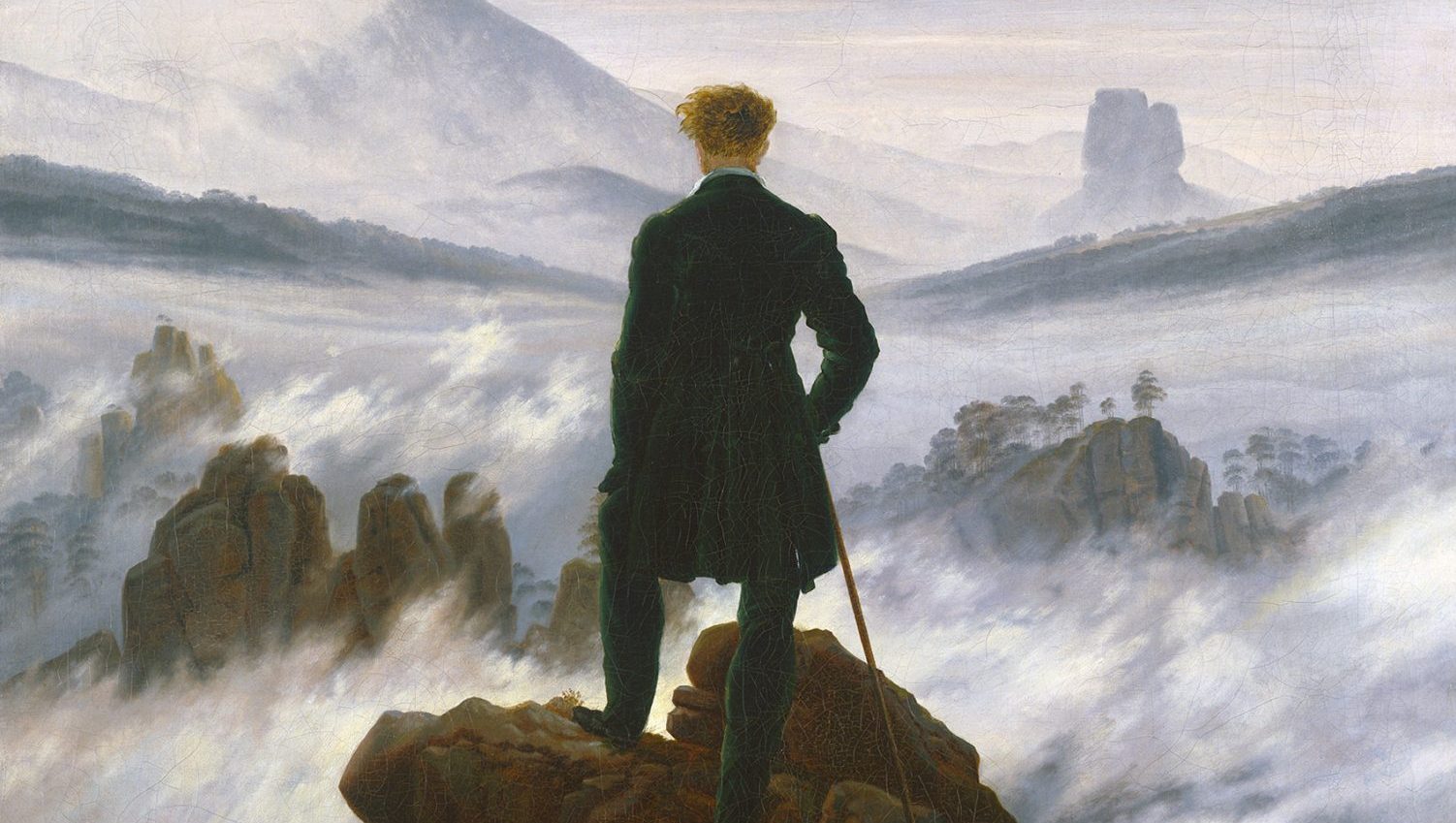

Early in 2023, climate change protesters picked on the most recognised picture in the whole, substantial collection of the Hamburg Kunsthalle. Over the world-famous Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog, they were about to glue a modern pastiche, in which the lone male figure, seen from behind, surveys not a sea of fog, but raging flames and red heat. A quick-witted member of staff intervened, and the activists, with equal alacrity, switched to glueing their version of the Wanderer to the floor, scattering over it ashes from Saxon Switzerland.

They had done their homework. The creator of the Wanderer had sketched in Sächsischen Schweiz four years before his painting, and had based the mountains in his imagined landscape upon those drawings. Attacking the Wanderer was on a par with singling out the Mona Lisa or Van Gogh’s Sunflowers. And the timing was not accidental. The Kunsthalle’s big new project is one of three exhibitions across Germany marking 250 years since the birth of Caspar David Friedrich, whose vivid and mysterious relationship with landscape inspired a wave of German romanticism.

The “wanderer” himself is a man dressed more for the salon than for the great outdoors, in his green velvet frock coat and trousers, with a stick that puts style over substance. The fantasy is autobiographical – other portraits of Friedrich suggest that he was justifiably pleased with his golden curls, not obscured here by one of the generous hats sported by his other male figures.

Today we expect to marvel at, and to record, the natural world, but Friedrich and his followers were entering new terrain. The industrial revolution had made the city rather than the land the focal point for work and for art, yet Friedrich was reassessing rural areas that had been considered primarily a cultivable asset, and investing it with aesthetic properties.

When, a few years after the Wanderer, he painted The Watzmann, another imagined landscape based on the drawings of a pupil, the public was irritated by it. For it contained no human figures at all, no paths to suggest connection with the built world, and no managed land. This admiration for the natural world informed his studies of ruins, over decades. Opportunist scrub has invaded the paving, trees sprout from the tops of walls as man’s creation crumbles, while the sun rises and sets in unfailing splendour.

Friedrich’s admiration for landscape began with a life-changing visit to the German island of Rügen. He was born in nearby Greifswald, on the mainland and close to the Baltic coast, and lived much of his life in Dresden after studying in Copenhagen. Working outdoors, and perfecting in the studio, he laid down the foundations for his later paintings, meticulously drawing plants and trees. These were not merely botanical studies, but were glimpses of the living world in their proper context. He was equally fascinated by rock formations, drawing multiple irregular shapes and hatching in their shadowy edges. Some but not all of these singular forms can be identified again, reappearing in later paintings.

Friedrich was in his thirties when, in 1810, he astonished the public at the Berlin Academy, of which he was a member, with his large and unconventional oil painting, Monk by the Sea. In it, a tiny male figure contemplates the vastness of creation with his hand to his head. He stands on a strip of beach or bleached rock, with a dark and low sea beyond. Above the horizon, four-fifths of the painting is sky. It is, for the time, an audacious composition. We now know from examination of the underdrawings that originally Friedrich had included vessels at sea, but that he subsequently painted over this suggestion that man could in any way harvest or master the ocean. Markus Bertsch, curator with Johannes Grave of the Kunsthalle exhibition, entitled Caspar David Friedrich: Art for a New Age, observes that with restoration the deleted boats have started to emerge again, ghosts rising from their watery grave. By the time of the oil sketch Evening (1824), the sky is even more dominant, the sliver of land below just containing the date and artist’s signature, scratched in with the end of his brush.

In Britain, Joseph Mallord William Turner was also looking skywards, and there are comparisons to be made between the two men, both having done the groundwork with quantities of early drawings and sketches. And in 1802, the London chemist and amateur meteorologist Luke Howard had assayed the first classification of the clouds, to the fascination of a public that during the age of the enlightenment, in the late 18th and early 19th century, had become excited by scientific ideas and experiments.

Clearly, however outlandish the scale, the presence of the lone monk reassured the public, and the picture was a sensation. It was even purchased by the Prussian royal family, not perhaps known for their adventures in art. In the same years, 1808 to 1810, that Friedrich was working on Monk by the Sea, he was also putting himself centre stage in Mountain Landscape with Rainbow. Dressed for the city in impractical white trews and striking red jacket, Friedrich himself surveys the land, dwarfed by a conical mountain that looms towards him like a broad-shouldered giant. The rainbow, which curves the full width of the composition, is a graceful, architectural arch. Friedrich adhered to the Christian faith of his strict Lutheran childhood, but this landscape is his cathedral.

In 1818, Friedrich married Caroline Bommer, the daughter of a dyer. The couple would have three children. Anecdotally the painting Chalk Cliffs on Rügen marks their honeymoon, on which they travelled to see relatives. The picture is dated that year, but the figures are unfamiliar.

Perhaps it marks a remembered incident, for the woman and one of the two men present are behaving curiously. She ventures towards the cliffs and waves below, clinging on to the branches of a bare or dread shrub. He is flat on his stomach, edging forwards and away from us, gripping long grasses, with his own wide-brimmed hat cast to one side. Surely that hat is signalling to us that the woman, who points down the cliff, has lost her bonnet? While Friedrich did not engage in narrative painting in the normal way, this odd couple are far removed in every way from the third figure, who does what figures are meant to do in Friedrich’s pictures: gaze into the distance, standing reverentially. And with his hat on.

Such possible whimsy was long gone by the time of a painting that so distressed the public, five years later, that it did not sell in Friedrich’s lifetime. The Sea of Ice (1823-24) must have baffled viewers, fully 200 years ago, just as in Britain Turner was beginning to confuse his critics. Both men were experimenting with colour, finding yellows and mauves where others thought they saw only white.

The ice that stacks up menacingly in Friedrich’s painting has flashes of orange, purple and green. Friedrich had seen rare ice floes on the River Elbe during a particularly harsh winter. Polar expeditions and the search for a north-west passage were making headlines, and many ships were lost. In the picture, one of them lies marooned and frozen in, so that its jagged outline has fused with the harsh angles of the shards of ice. Unlike in Monk by the Sea, Friedrich has allowed us to see human engagement with the elements – but it has failed spectacularly.

The daring use of colour is one of the many aspects of Friedrich’s work that have inspired today’s artists in the Hamburg show. Another, present-day artist excited by the natural world, Olafur Eliasson, extracts the colours of The Sea of Ice and distils them into a mauvy colour wheel. The Wanderer, as one of the most familiar figures in all art, has prompted many imitators, including Elina Brotherus. She puts herself into the familiar landscape, back to the viewer, her tailored coat nipped in at the waist, an unescorted female wanderer for our time.

Swaantje Güntzel similarly updates Friedrich’s contemplative views, chucking a yoghurt pot into the water. She continues the theme of the despoiling of the natural world by staring at The Sea of Ice from a gallery bench that is surrounded by an iceberg of discarded bottles and packaging.

Hiroyuki Masuyama recreates The Sea of Ice exactly in a photomontage, while Lyoudmila Milanova uses acrylic sheets to make a cloud appear to float in mid-air.

To its credit, the Kunsthalle records the climate activists’ unscripted intervention with a vivid photograph of Lula Merlo’s Wanderer above a Sea of Fire, and words from “the last generation” by Eika Jacob.

The aim of the big Caspar David Friedrich year, 2024, is to show that he is relevant to today’s gallery-going public, and not out of time. The initiative, with exhibitions to follow in Dresden and Berlin, is the latest peak in a career whose reputation has gone up and down like one of Friedrich’s formidable horizons. By the time of his death at the age of 65 in 1840, he was out of fashion.

A century later he was unlucky to be championed by Hitler, who hijacked the artist’s reverence for German landscape, in contrast to the abstraction of “degenerate” artists such as Wassily Kandinsky and Ernst Ludwig Kirchner. That brief and unwanted popularity ensured more years in the doldrums. But now Friedrich is being rediscovered as a pioneer of environmentalism. Says the federal minister of culture, Claudia Roth: “The works of Caspar David Friedrich come across as a painterly plea to protect nature in all its beauty and vulnerability.”

Caspar David Friedrich: Art for a New Era, Kunsthalle, Hamburg until April 1; Caspar David Friedrich: Infinite Landscapes, Alte Nationalgalerie, Berlin, April 19 to August 4; Caspar David Friedrich: Where it all Started, Albertinum and Kupferstich-Kabinett, Dresden, August 24 to January 5, 2025