It is the destiny of the polymath to remain less distinguished than they perhaps deserve to be. There is always a suspicion that, by not focusing on one area of expertise, a person must be flighty or whimsical, a mere dabbler in one thing and another. Specialists win more respect than those who excel in different fields, which never feels entirely fair.

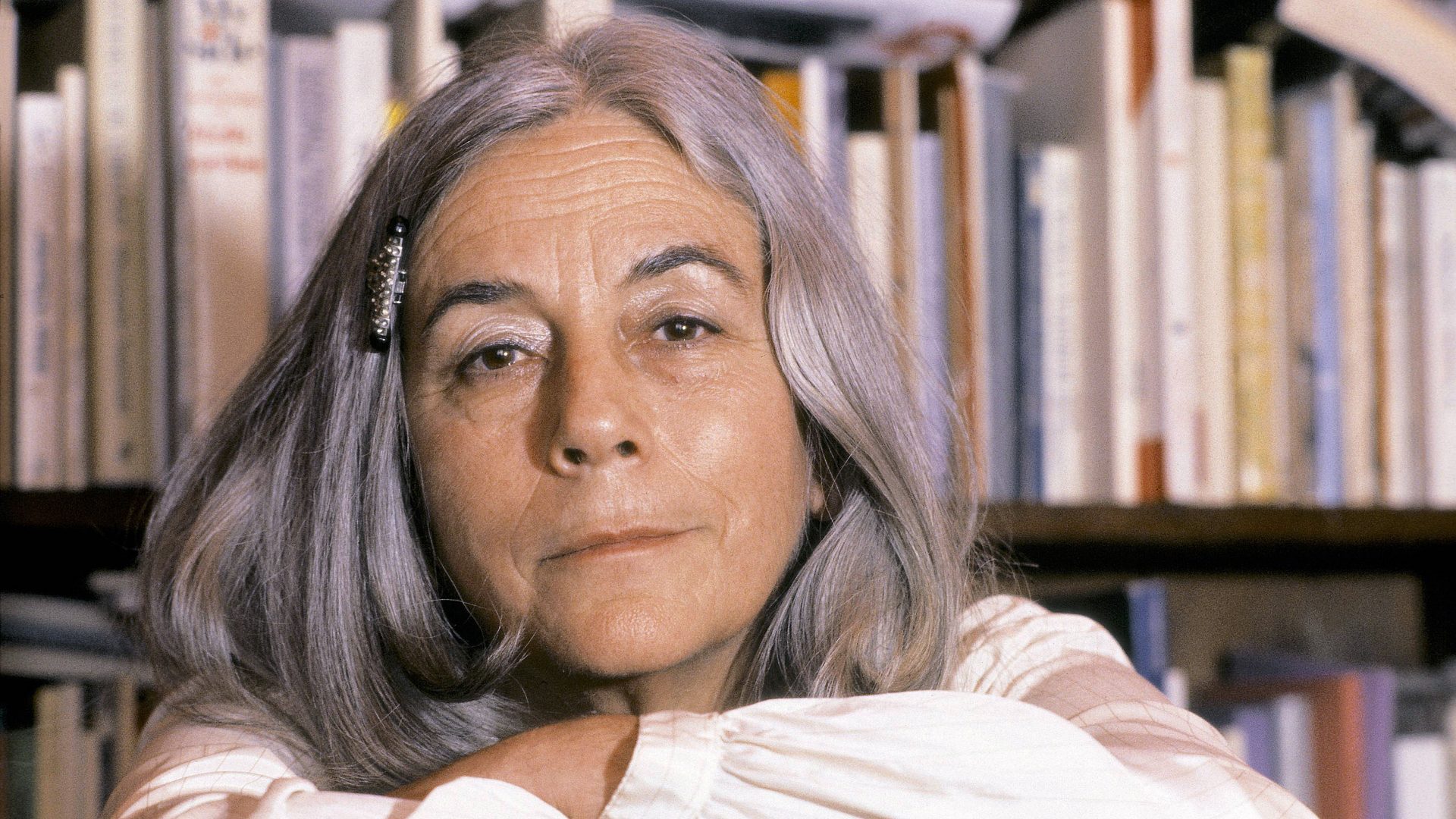

One exception to that polymath rule was Carmen Martín Gaite, a proper, old-fashioned woman of letters. She wrote novels, short stories, poetry, plays, children’s stories and books for young adults, literary criticism, essays, television scripts, she translated some of the greatest works of European literature into Spanish and her letter writing and diary-keeping were so good they warranted published collections after her death.

Having grown up in a Francoist Spain that viewed independent women as suspicious to the point of hostility, Gaite, who was 50 when Franco died in

1975, became one of the nation’s leading cultural figures. She received a string of prestigious awards, including the National Literature Award twice, and became only the second woman to be elected to the Royal Spanish Academy. For all her own success she was renowned for her generosity to younger writers like Juan José Millás, Marcos Giralt Torrente, Soledad Puértolas and Belén Gopegui, who all credited Gaite’s kindness as a key part of their literary development.

Whatever her outlet, Gaite always derived immense pleasure from reactions to her work and never lost her gratitude for “the luck of being able to do what I like and the luck that what I write is enjoyed by readers and critics alike. I count that as a miracle”.

She was born and raised in the city of Salamanca, where her father worked as a notary, but spent most of her childhood summers with her grandparents in Galicia where she would set many of her novels.

Her father was determined that his daughter would not be educated by a religious institution, which in 1930s Catholic Spain left home-schooling as

the only option. Her parents planned to send her to Madrid for her final two

school years, as they had with Carmen’s older sister Ana, but the outbreak of the Spanish civil war in 1936 changed that (it also led, in the first month of the war, to the execution of Gaite’s uncle, a well-known local socialist).

Instead, Gaite attended the Women’s School Institute in Salamanca where she was taught by the eminent philologist and historian of literature Rafael Lapesa and the author Salvador Fernández Ramírez, both of whom would go on to be elected to the Royal Spanish Academy and were key early influences on Gaite.

Her first published work was a series of poems that appeared in the student magazine of the University of Salamanca, from which she graduated with a degree in philology. Postgraduate study in Coimbra and Cannes followed before a move to Madrid to embark on a doctoral thesis analysing Galician-Portuguese songbooks from the 18th century.

While her future seemed to lie in the dusty silence of the academic library, Gaite found herself being drawn more and more towards creative writing, publishing a poem here and a short story there until her thesis began to fall

behind her literary output. When a brush with typhus in her mid-20s proved

almost fatal, the subsequent re-evaluation of her future meant that her doctorate was abandoned as she became increasingly entwined with a group of literary bohemians, the appeal of long afternoons in cafes soon eclipsing the cloistered world of academia.

Gaite was introduced to that world by the writer Ignacio Aldecoa, with whom

she had studied at university in Salamanca, and she was soon whiling away evenings talking literature with some of Madrid’s most significant modern writers like Josefina Rodríguez, Alfonso Sastre, Medardo Fraile, Jesús Fernández Santos and Rafael Sánchez Ferlosio, whom she would marry in 1953.

Ferlosio was of Italian extraction and their honeymoon was a protracted stay there, basing themselves at the family home in Rome and taking extended trips to Venice, Florence and Naples. The months she spent in Italy had a profound influence on Gaite, introducing her to the work of Italo Svevo and Cesare Pavese among other contemporary authors and instilling a lifelong love of the Italian language.

The following year saw the publication of her first novella El Balneario, (The Spa), but it was her 1957 novel Entre visillos, (Behind the Curtains), that launched Gaite to literary stardom. Considered one of the great Spanish novels of the 20th century, Entre visillos documents the apparently trivial conversations and uneventful lives of a group of young women in Salamanca until the charismatic Pablo Klein arrives in the city to teach German at the university, transforming their structured existence.

Entre visillos won the prestigious Premio Nadal award in its year of publication and still features in discussions about the greatest works of Spanish fiction. The book also introduced the concept of la chica rara, the weird girl, a type Gaite recognised in Franco’s Spain – the outsider acting in quiet rebellion against the social norms of the era.

Gaite would return regularly to la chica rasa, even writing a non-fiction book on the subject published in 1987 called Usos amorosos de la post-guerra Española, (Customs of Courtship in Postwar Spain), effectively a social history of the 1940s and 1950s that became a bestseller and introduced Gaite’s fiction to a new generation.

That success came a decade after El cuarto de atrás, (The Back Room), a typical

Gaite novel that moved along a fuzzy line between fantasy and reality that won her the National Literary Award in 1978, the first woman to receive a prize she would win again in 1994 in recognition for her entire body of work.

By then Gaite was still enjoying the revived success prompted by Usos amorosos, the three novels she wrote during the 1990s selling more than 300,000 copies each and sending more people to her back catalogue, not to

mention the string of history books she had written during the 1960s (she finally secured her doctorate in 1972 at the age of 46). In addition, she translated several great novels into Spanish, including Madame Bovary, Jane Eyre, Wuthering Heights and books by authors notoriously difficult to translate, such as Virginia Woolf and Primo Levi.

For all her polymathy, Gaite’s novels have proved to be her enduring legacy. The quality of her writing and the timeless topics she documented triggered regular waves of rediscovery, the readers of the 1970s seeking out her 1950s work, a new audience in the 1990s looking back to her fiction from the 1970s. This constant cycle pleased Gaite immensely.

“I take great satisfaction in pleasing my readers,” she said towards the end of her life, “and especially the fact that new readers are arriving all the time. This reassures me that I have not thrown in the towel and become formulaic. All I can do is write from what I know. Thankfully the reader seems to identify with that.”