I complained about the weather in Cannes’ first week, so naturally the sun came out with a vengeance and I started the second in a stifling studio atop the Palais, guesting on a French radio show, Affinités Culturelles. Hosted by the excellent Tewfik Hakem, it airs on France Culture.

We’re debating the differences between film critics in different countries, particularly how Anglo-Saxon writers verge from the theoretical orthodoxies of French critics. England’s newspaper critics, I say, stem from a tradition of ex-war or sports reporters given a cushy billet, and our mission is to produce

entertaining copy, not to evaluate mise-en-scene. “So you’re saying English critics feel with their heart, and French critics think with their head?” asks Tewfik, just about summing it up.

How did my heart feel about the Cannes films this year, then? I didn’t see as many as I’d like to. My new career as a producer has taken me out of the screening room and into meetings and production-funding panel sessions. I saw about half my usual quota of two dozen films, but began to find these producer meetings all rather fascinating, useful and exciting – three adjectives I couldn’t use about yet another Wes Anderson movie premiering at Cannes.

After his tedious, condescending 2021 doodle The French Dispatch, here came Asteroid City, set in a 1950s desert town (population 87) where a meteorite crater provides the only attraction and where a convention takes place for “junior stargazers and space cadets”, rewarding America’s geekiest teenagers for their discoveries and inventions. Housed in a purpose-built camp of bright wooden huts, chaperoned by their parents, an alien event occurs, leading the US government to seal off Asteroid City and detain all inhabitants pending quarantine tests. A week of listlessness, ennui and experiments result, with an all-star cast.

It is perhaps heretic to whisper it in Cannes, but outside the bubble, there’s a growing holler for Anderson to just shut up. Once you enter his doll’s-house worlds, there’s no escape from the twee tedium and geek-child self-satisfaction. I simply want to throw all the dolls out of the top-floor window.

Even when the dolls are perfectly drawn figurines of actors including Tilda Swinton, Scarlett Johansson, Edward Norton, Bryan Cranston, Liev Schreiber and, here, Tom Hanks and Steve Carell joining the quirky playgroup for the first time.

More irritating still is that there are occasional rays of genuine humour in this particular instalment, little gags or details that actually made me smile.

Most of these came in the meta-textual framing device – namely it’s all

a production of an experimental New York theatre troupe putting on a show

called Asteroid City, leading to many of the actors attending a Lee Strasberg-style “actor’s studio workshop” led by Willem Dafoe, and improvising their feelings around a script which Norton’s playwright is tapping out.

The whole thing – including the director’s ongoing inclusion in the Cannes Competition – feels like a situationist joke. And nobody seems to mind that the only black character ever to pop up in Anderson’s cutesy world is the Brazilian singer Seu Jorge. Or sometimes there’s a brown character, too, played by Tony Revolori. “J’en ai ras-le-bol”, as I said on French radio – I am up to the brim of the bowl with it, something like that.

Talking of overflowing cooking receptacles, there were plenty on show in The Pot-au-Feu, a drooling French period food movie that won the prize for best director for Vietnam’s Tranh Anh Hung.

With films including Cyclo, The Scent of Green Papaya and At The Height of

Summer, this film-maker has made some of the most beautiful examples

of east-meets-west movies. His adaptation of Murakami’s Norwegian Wood in 2010 was less successful, but always emotionally interesting. But now his return to Cannes – where Papaya won the Camera d’Or for best first film in 1993 – marked his first triumph there in 30 years.

The Pot-au-Feu is beautiful, no doubt about that. It stars Juliette Binoche and Benoît Magimel as a gourmet and his cook who spend their days in a lovely country house, with its own herb and vegetable garden, rustling up classic dishes and wine pairings. I’m not quite sure who they do it for – it’s not a hotel or a restaurant, but a few pompous fat local dignitaries do turn up for dinner and slurp over the consommé, before gobbling down the turbot and still finding room for the côte de boeuf and dessert. I even discovered that Baked Alaska in French is Omelette Norvegienne.

Binoche stays in the kitchen, preparing her stocks and bouillons and perfecting her browning of poultry pieces while every now and then collapsing with tiredness before gamely carrying on deboning the game. Magimel frets about his wine cellar and the perfect menu for a visiting prince– he decides on a Pot-au-Feu, a basic family stew. Is this a dish fit for royalty, gasp the plump dignitaries? He will make it so.

Meanwhile, Binoche’s fainting spells become more pronounced, putting the

prince’s Pot-Au-Feu dinner under threat. Will the remarkable palette of a local peasant girl who has come under Binoche’s kindly yet exacting tutelage

be able to pull off this remarkable culinary coup?

Tranh’s camera circles the cosy kitchen, dives into the pots and pans to observe the sizzle of a sofrito or the poaching of fish heads. It’s all so very

handsome and dreamy, yet – let’s be honest – also rather dull.

What do we make of the continued presence of Italian auteur Nanni Moretti? We owe his light, autobiographical films a huge debt, his intellectual questioning so often a delight, in Dear Diary, Aprile and, the Palme d’Or winner that has made me cry the most, The Son’s Room, from 2001. His last entry here a couple of years ago, Three Floors, was generally agreed on to be dreadful.

A Brighter Tomorrow is, at least, some improvement, a return to his more playful film-based comedies, in which the director himself plays an arthouse film-maker having marital problems – his wife and producer is thinking of leaving him – and whose career has hit the buffers largely due to his own inability to change with the market. He’s trying to make a film about the visit of a Hungarian circus to an Italian communist village in 1957 just as the Soviets are invading Budapest. His wife is making a Korean action movie.

The various parts don’t all come together as sweetly as Moretti might have liked, and his own acting feels vacant and slow. But there are some decent gags and a few nice ideas here, including a scene subtly updating the classic Moretti image of him riding his old Vespa through the city: now, he’s on an electric scooter, in the company of the French actor Mathieu Amalric, scouting locations in a working-class district of Rome.

Continuing the dusting-off of old favourites, along came Wim Wenders

with Perfect Days, for which veteran Japanese actor Koji Yakusho won Best Actor. Yakusho starred in Shōhei Imamura’s Palme d’Or winner The Eel in 1997 and featured in the original huge ballroom hit Shall We Dance? before it was remade with Richard Gere and Jennifer Lopez. He’s excellent here, as a Tokyo toilet cleaner quietly and stoically going about his business cleaning up everyone else’s.

I liked the film and Wenders’ ascetic approach, with Yakusho’s face the main conveyor of emotion as he tidies his neat little flat and merrily pootles off to work in his van, drinking coffee from a can in a vending machine and inserting a cassette tape from his large collection into the vehicle’s player to

underscore his way with a classic hit from Otis Redding or Van Morrison, or Patti Smith, or the Velvet Underground’s Pale Blue Eyes.

We watch him do his ablutions in public baths and have the occasional lonely dinner in a ramen place in a mall with the baseball on in the background and his trusty analogue Olympus camera by his side.

It’s all very meditative and jolly, until his niece turns up and we’re drawn to

contemplate a bit more of this character’s past, discovering he’s from a wealthy family on whom he’s turned his back for this more simple life. Gently, we begin to question existence and happiness, all through the simple

pleasures of the wind in the trees, and noughts and crosses games left in a loo to be filled in by the next occupant. I liked it – and wish I hadn’t thrown away all my cassette tapes, which are now, it appears, going for a fortune in Japan’s record shops.

Amid all the veteran regulars at Cannes, none stands taller than Ken Loach, who accompanied his 14th competition entry up the red steps, with The Old Oak billed by the nigh-on 87-year-old director as his final film. He’s won two Palmes d’Or – for The Wind that Shakes the Barley and for I, Daniel Blake – and he was going for a record-breaking third, which would have been a sentimental choice but hard to deny. No one makes cinema like Loach (and his team of writer Paul Laverty and producer Rebecca O’Brien) and nobody says the things his cinema shouts.

The Old Oak isn’t perfectly performed or subtly written or even deftly plotted, but it speaks from the heart, to the heart. We’re in a blighted ex-mining town near Durham, where vacant housing results in a busload of Syrian refugees being given homes, much to the discomfort of the overlooked, under-employed locals.

Far from making us love the locals, Loach portrays the working-class whites as poisonous xenophobes, wholly unprepared to offer any kind of solidarity to the Syrians. Only kind-hearted pub owner TJ Ballantyne finds a spark of generosity, opening up his long-sealed back room for a Syrian woman on whom he takes pity and who discovers, in there, a series of striking portraits of the community from the 1980s miners’ strike, scenes of picketing and of solidarity and of communal food-eating sessions that brought families together and saved lives.

You couldn’t get more Loachian and misty-eyed if you were lampooning it, but there remains such moral seriousness to the work that it would be churlish and philistine to dismiss it. The pub regulars are a seething gathering of resentment – how have they forgotten the spirit of the strike that their fathers carried on so bravely against Thatcher? How have these once-noble working folk become riven with hate and racism?

It’s a knotty and brave question, and I don’t think I’ve seen Loach and Laverty question “their people” with such honesty and such risk before. How have the salt-of-the-earth types become so poisoned? The film is set in 2016 but doesn’t mention Brexit at all, nor the shift of the red wall to the Conservatives in the last election.

The finale doesn’t quite make sense to me, or at least frustrated my sense of

where the story should be headed, but he’s still a director capable of leaving a lump in your throat as well as thorny political issues ringing in your head.

So it was a Cannes of veterans, none more so than Indiana Jones himself, the explorer now seeking the Dial of Destiny and still played by Harrison Ford, though caked with de-ageing special effects that make some of his escapades look more like a badly drawn comic strip than ever.

His new sidekick is played by Phoebe Waller-Bridge in a “jolly hockey sticks” manner that peps things up a bit, but she’s no action star.

Together, aided by John Rhys Davies’s booming Sallah, they have to wrest some gizmo – Archimedes’ legendary Dial of Destiny – from the hands of Nazi artefact hunter Mads Mikkelsen. The plot is partly in the past, then very much in the past, then in the 1980s, I think, and is vaguely about ageing and antiquity and turning back time.

It’s all a bit of a mess, and the eponymous Dial looks like it has come out of a cereal packet, but maybe that’s part of the old-fashioned Saturday morning matinee Boys’ Own fun that was at the heart of Spielberg’s original. I saw it with my dad at the Ionic on the Finchley Road in 1981. We both loved it so much and laughed and were thrilled throughout, and after he bought me the biggest bag of chocolate raisins I was a bit sick in the car on the way home.

All that was wafting back to me – not the sick, thankfully – as I watched Indiana Jones again. What a strange artefact cinema itself can become, a

repository of memories, a trigger for a gateway to the past.

That’s all lovely. But if cinema doesn’t come up with some new tricks, some new voices, there’s a risk, I couldn’t help feeling over these last days of Cannes, that audiences will not renew. And we will all be stuck in an arthouse loop of Wes, Wenders, Loach, Nuri Bilge Ceylan, Aki Kaurismäki and Moretti lasting for eternity and a day… or at least until the excitement of next year’s Cannes line-up.

THE WINNERS

So, for the first year in 25 at Cannes, I missed the winner – in fact two of the major winners. But I feel you should know about both of them, because hearing the buzz around Cannes winners is just as important as actually seeing them.

Justine Triet’s Anatomy of a Fall took the Palme d’Or, the second time it has gone to a French female director in three years, following Julia Ducournau’s Titane in 2021. This an icily gripping courtroom drama defrosting the relationship between a writer (the always-excellent Sandra Hüller) and her

husband who has fallen – or was he pushed? – to his death from their holiday ski chalet.

I enjoyed this director’s previous competition entrant Sybil, a juicy murder melodrama set on Stromboli, a few years ago, and can’t wait to be wrapped in the complex ambiguities of this one.

Another important winner I missed was the Un Certain Regard field, where first and second-time voices and more experimental work is generally housed. This year, a UK victory should be heralded, a film called How To Have Sex and directed by Molly Manning Walker, a story of four young women on a big boozy bender of a holiday in a Mediterranean resort. It won the best film award for that section, the first time a British movie has achieved that since Jasmin Dizdar’s Beautiful People in 1999.

Molly was quite the presence in Cannes this year. I met her, and her mum and, having got the call back to come and get her prize, she made a literal mad dash to the ceremony while its chairman, John C Reilly, stalled proceedings with a song to allow time for Molly’s sprint up the Palais steps to claim her prize, still in shorts, T-shirt and trainers and as exhausted as a marathon runner.

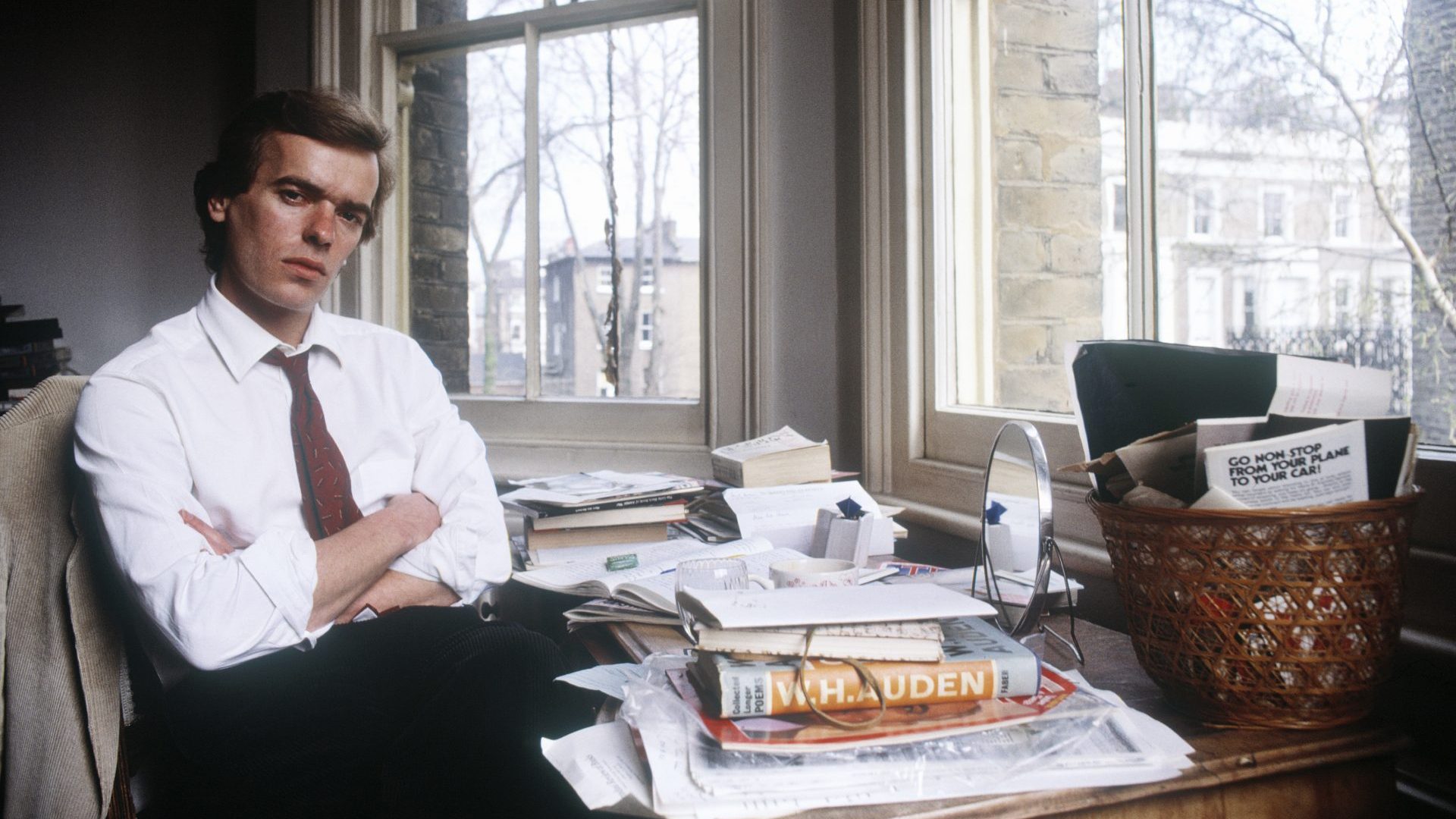

Other prizes of note were the Grand Prix runners-up spot awards to Jonathan Glazer’s The Zone of Interest, a film that will certainly become a major talking point of the year to come. Also starring Sandra Hüller, it stands as a fitting tribute to the late Martin Amis, having been based on his 2014 novel.

Best screenplay went to playwright Yuji Sakamoto for his complex, multi-angled look at an incident of child abuse in Hirokazu Kore-Eda’s Monster – although that film should also be noted for a Best Music prize that doesn’t exist, for a beautiful final score by the late Ryuichi Sakamoto.