Faces vaporised, torsos punctured, a fragmenting globe… The opening images in an enthralling new exhibition at the Barbican Art Gallery in London do not shy away from the realities of armed conflict. Their creators knew first-hand about suffering, emerging from the second world war to a changed world.

Nearly three years in the making, Postwar Modern was turned on its axis just before its opening. What set out to be a story concluded – of war, peace, reconciliation and rebuilding – was wrong-footed by Vladimir Putin, and talk of a third world war. And yet, for all the shattered imagery of its first rooms, human creativity triumphs emphatically over the devastation wreaked by vain nihilists.

Not for these artists the relative comfort of Cornwall – despite being a celebration of mid-century art in Britain there is no Barbara Hepworth, no Ben Nicholson. The omission of Henry Moore is harder to understand, his records of bomb shelters in the London underground among the most

poignant of war records.

No surprise, perhaps, that after experiencing horrors beyond imagining, sculptors used the full three dimensions to memorialise the best and worst of humanity. William Turnbull, an RAF pilot, seems to look down from the skies at miniature ground plans, solitary buildings or their husks, poking up like teeth. Elizabeth Frink, who grew up near an RAF station in Suffolk, took to the air with her Harbinger birds, stalking skeletally. Also hovering above reality is Lynn Chadwick’s vast and prehistoric Fisheater, commissioned for the Festival of Britain in 1951, now owned by the Tate. And it is Chadwick again who roll the ugliness of war into one chrysalis, a sinister grenade, or grub, that is primed or sleeping. But which? Uncertainty and shattered trust, sensations that have become newly strong for postwar generations, abound.

But so does the extraordinary resilience of humanity, and its capacity to reset. Of the 48 artists in the show many were migrants to Britain, among them Francis Newton Souza who so clearly identifies with his pierced St Sebastian and crucified Christ.

Scourged by war, the human body slogged on in the face of continuing shortages and deprivations, and adapted to an increasingly mechanised

world. Under the male or female gaze, mid-century anatomy takes a forked

road. The exposed organs of Hungarian refugee Magda Cordell’s larger-than-life women ooze with fluid and erupt in clots, the whole a surprisingly joyous celebration of physicality, with all its inconveniences and imperfections. “In your lifetime you are remade countless times,” marvelled the artist. Polish refugee Franciszka Themerson confronts the absurdity and erratic nature of life with frank and anxious faces, the occasional upside-down figure a reminder that nothing in life is stable.

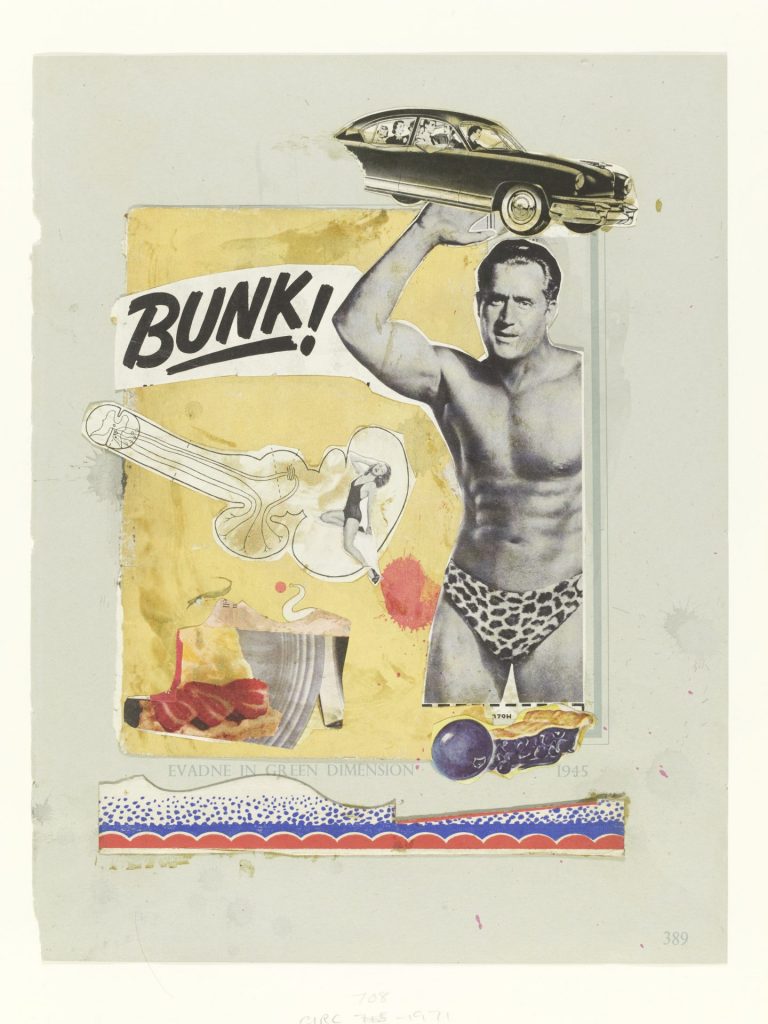

John McHale, on the other hand, accepts and indeed positively welcomes

technology into his family unit: mother, father and children modified, automated, their wayward curves squared off. He and Cordell married in 1961. And Eduardo Paolozzi, raised in Scotland by fascist-sympathising parents in the ice-cream business, also harnesses a mechanical new age, grafting cogs and bars on to his beings.

After the fracturing of war, this was a great period for forming groups, as

artists ultimately exalted in a world repaired. In 1951 Paolozzi combined

with Cordell, McHale and Turnbull in the Independent Group. He then

established Group Six, with, among others, Nigel Henderson, whose Bosch-like monsters writhe around the body of a child, petrified by the eruption of Vesuvius at Pompeii. Group Six exhibited together at the landmark This Is Tomorrow exhibition at Whitechapel Gallery, east London, in 1956, as a brighter age unfolded.

It took almost a decade after the end of the war for food rationing to finish (and petrol rationing was briefly reintroduced in 1956-57). It’s hard not to wonder whether we too are one day going to feel like husband-and-wife artists John Bratby and Jean Cooke, displaying such food as is obtainable, on a table top tilted for a better look. Look, we’ve got Kellogg’s Cornflakes! And Shredded Wheat!

Art critic David Sylvester dubbed this new, matter-of-fact art Kitchen Sink, the term also picked up by dramatists. At the time of these artworks, on stage and screen were John Osborne, with Look Back in Anger and Shelagh Delaney’s A Taste of Honey. Meanwhile in Nottingham, novelist Alan Sillitoe was stripping working life to the bare bones in Saturday Night and Sunday Morning.

Artist after artist, group after group, explored new routes to express the postwar world’s altered state. Both Leon Kossoff and Frank Auerbach took

refuge in Britain from Nazi persecution. With paint scooped on then gouged away, they re-created on canvas the stricken bomb sites of their adopted home and the doggedly orderly suburbs. But when Kossoff’s lines meet at Willesden Junction it is not clear whether this is a safe haven or the end of the world.

As confidence returned, artists including Victor Pasmore, a conscientious objector, envisaged a clear-cut new world, the clean lines of constructivism both harking back to Russian artists’ break with old traditions, and picking out a singular new look for Britain that was not simply abstracting from observed scenes. At first glance organised and geometric, his works are at heart more poetic than rigorous. Patrick Heron, a fellow conscientious objector, broke out in the 1950s into joyous eruptions of pure colour. “I now explore with a sense of freedom quite denied me while I had to keep half an eye on a subject,” he said in 1956.

William Scott, who served in the Royal Army Ordnance Corps and with the

Royal Engineers, also pared life down to its simplest, most satisfyingly simple structures and colour blocks, squashed circles on warm blue suggesting organic and man-made forms – cups, jugs – that are both satisfying and restful. After the agonised art of the immediate aftermath

of the war, by the mid-60s there is calm, colour and freedom of expression. As we live through another tumultuous period, there is some comfort to be

found in this reassuring cycle.

Postwar Modern: New Art in Britain 1945-1965 is at the Barbican Art Gallery,

London until June 26

Claudia Pritchard is a freelance journalist who writes about the visual arts, opera and classical music