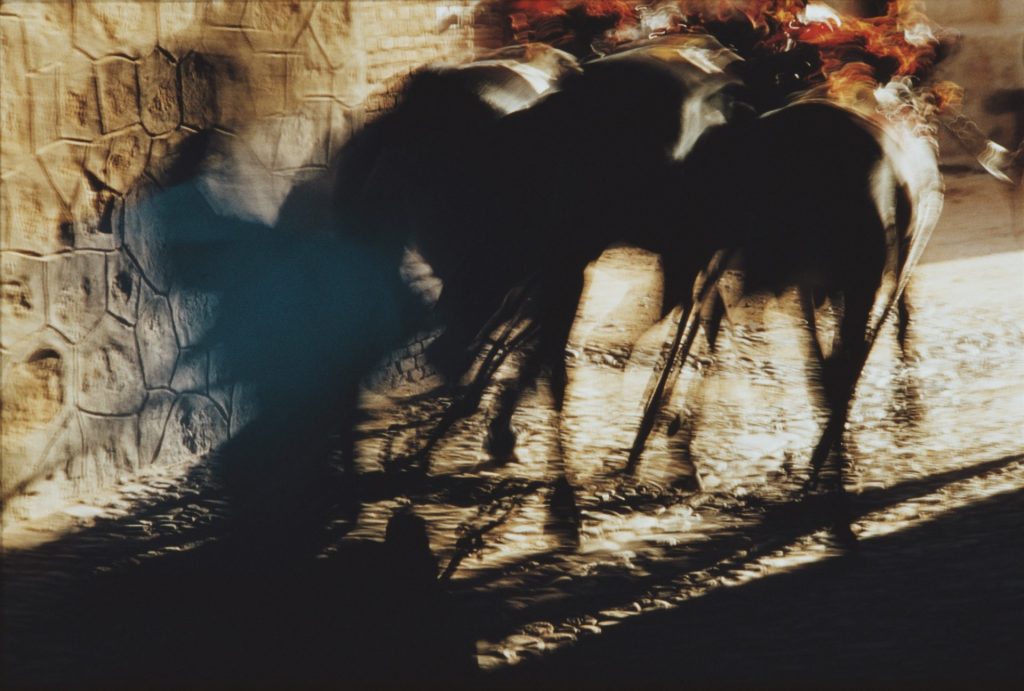

It is bullfighting season again in Spain. The spectators are back in the heavily stratified bullrings, where tickets in the more shaded stands are considerably more expensive than the seats located in what is colloquially referred to as the “sun and flies” economy side of the arena.

The matadors are back too. In the winter months, many bullfighters decamp to Latin America, where questions over the future of what has traditionally been known as Spain’s “national fiesta” are increasingly raised. A legal ban in Mexico City was recently overturned: all 42,000 tickets for the first post-prohibition corrida, held on January 28 in the world’s largest bullring, sold out.

Animal rights protesters physically attacked some attendees, but this proved to be counter-productive, forging a link between attending an archaic spectacle and resisting modern-day censorship. After years of dwindling ticket sales, the next two corridas to be held in the Mexican capital also sold out.

But Mexico City was a sign of things to come. The spectators and matadors may be back, but also back is the ongoing controversy about what is to its opponents a blood sport, to its aficionados a cultural event.

Those in the shade or with the sun and flies are united by their disapproval at statements by Spain’s incoming minister of culture, the Catalan-born Ernest Urtasun, against bullfighting.

Since the beginning of his political career, Urtasun has emphasised his personal and political commitment to prohibition. None of his predecessors have ever been so explicit. Thus far, however, Urtasun’s comments have only boosted ticket sales, with many spectators expressing a moral responsibility to buy a ticket to defend a beleaguered cultural industry.

In Valdemorillo, the incoming conservative local council may have banned a theatrical production of Orlando last summer, but pouring public money into the annual traditional corridas in February was pitched as an investment in tradition and freedom. They are playing to the gallery: the vast majority of the inhabitants of this small town on the outskirts of Greater Madrid are far more interested in the bulls than they are in Virginia Woolf. It is a matter of civil pride that they stage the year’s first corridas.

The arena now has a roof, but this wasn’t always the case. A small museum populated with the dissected heads of bulls also includes photographs from 1983’s infamous “snowy” corrida.

With return tickets costing €10, the occupants of a bus ferrying ticketholders to Valdemorillo from Madrid’s principal bullring, Las Ventas, were mostly sitting in the cheap, sunny seats. Many of them were of pensionable age, with a number attending the spectacle on their own.

After purchasing a remarkably cheap (€5), quadruple gin and tonic at the bar, I took a front-row seat in the shady side next to José Antonio, a medical doctor born in Salamanca who now practices in Catalonia (where bullfighting was banned in 2011). He had made the journey from Barcelona by car with his Seville-born wife. Knowledgeable and affable, we didn’t talk politics, but his not having ever learned Catalan was an indication of where his loyalties lie.

A one-minute silence before the corrida for the civil guards recently killed chasing drug traffickers by boat outside Cádiz ought to transcend politics, but such gestures are hardly politically neutral. Politically progressive metropolitan elites are not that well-represented among the Spanish Civil Guard or the taurine lobby.

The three matadors on the bill all hailed from Extremadura or Andalucía, among the poorest regions of Spain. Born in Seville, the victor of the evening was the 33-year-old Juan Ortega, a fixture of the gossip press after jilting his bride-to-be at the altar last December.

For all its machismo (Mario Alcalde, an apprentice bullfighter incorrectly referred to as a fully fledged matador in the British press, recently caused shockwaves by coming out of the closet), spectators at corridas are inveterate gossips. A key selling point of sitting in the front row is being spotted and often photographed in the most expensive seats as well as having privileged views of the callejón, the area between the arena and the stands where the matadors sit in wait (there is no backstage) while managers and others involved in the business of bullfighting survey the action.

The pressure of performing may be less in Valdemorillo than in a world-class ring like Mexico or Madrid, but the nervous tics of matadors are legion. The youngest, Ginés Marín (whose team includes his Civil Guard father, Guillermo, who requests unpaid leave from his day job whenever his son performs), pulls off crowd-pleasing tricks like going down on his knees in front of the bull to dispense with nervous energy.

Thirty-six-year-old Alejandro Talavante was once a world-class matador, still capable of great performances albeit with less regularity than a few years ago. Managed by Simón Casas, a French-born 76-year-old who remains in remarkably good shape given his colossal intake of gin and tonics, Talavante has a disciplined and demanding fitness regime (Richard Dunwoody, the former Grand National winner-turned-taurine photographer, tells me that elite matadors are in better shape than top jockeys) that so far has not extended to him renouncing his compulsive habit of a cheeky cigarette or three.

Getting close to the action is not without risks. A week later in Ciudad Rodrigo, a historic town in the Salamanca region close to the Portuguese border, a teenage girl in front of me had her new coat splattered with blood as the bull charged against the boards of a makeshift bullring erected in the main square.

Tickets for the Ciudad Rodrigo bullfights are not available to buy online. Proprietors responsible for constructing individual sections of the stands have a license to charge a fixed entrance fee, payable in cash.

Paco, my point of contact, was a consummate professional. He erected an excellent makeshift ladder and stops non-paying customers from climbing up to catch a glimpse of the action below. Forget the reconstructed Globe Theatre on London’s South Bank, anyone wanting an idea of what attending popular entertainment in early modern Europe might have been like would be well advised to come here.

Armed with another cheap potent gin and tonic, it was difficult to give credit to Paco’s complaint that the local authorities had become health and safety obsessed in recent years as I whacked my head climbing to the stands where a perilously positioned drunk of pensionable age danced to some 1990s techno.

Almost all of the corridas sell out, especially if a star matador (many of whom train in local ranches) rocks up – Ortega’s triumph in Valdemorillo raised expectations about his appearance to fever pitch.

An equivalent to, say, York Hall in Bethnal Green for the boxing fraternity, Ciudad Rodrigo also boasts of being a launching pad for new talent. There is a competition for students from the Salamanca bullfighting school, facing smaller bulls (novillos).

Audiences can be rowdy but those in the stands are less inebriated than those in the streets outside. The nerves of one young man at the so-called moment of truth were shattered when he failed to make a clean kill and took multiple bad attempts (the prolonged cruelty of which render difficult any defence of the national fiesta) to dispense with his opponent – an unexpected blast of ABBA’s Waterloo from a ghetto-blaster being carried around by a troupe of middle-aged men and women wandering the streets in fancy dress couldn’t have helped.

Many Spanish towns celebrate Carnival in February. In a tradition stretching back centuries, Ciudad Rodrigo boasts the sole bull-themed Carnival in the peninsula (there are some others in Latin America). Hosting the year’s first major encierros (bull-runs through the streets), the Carnival provides the opportunity for the young men (and the occasional young woman) who travel around the county to participate in them during the main bullfighting season to reconnect.

The bulls are less imposing than those let loose in Pamplona, but spectators get much closer to the action and the runners are more professional, with fewer foreigners inebriated by alcohol or tales by Hemingway. Another option is to watch from the many bars along the route, protected with metal bars to prevent errant bulls from trespassing.

Other popular festivities include capeas, where anyone is allowed into the main square to showcase their moves in front of a bull, and recortes, in which seasoned professionals showcase acrobatic displays in front of the bulls. A novelty this year was mimicking the increasingly popular Goya-themed professional corridas (in which matadors and their teams don 18th-century garb) by having those involved in the recortes adorned with period dress, albeit with the addition of lime green Nike trainers.

The politics of popular festivities in which bulls are taunted and tortured is complicated by Franco having banned Carnival celebrations (although a number of towns, Ciudad Rodrigo included, defied this prohibition). As a result, an association between liberty and bulls difficult to comprehend from the outside persists.

Floats brought into the arena after one of the bullfights made clear why a tough regime might be averse to such celebrations: alongside a replica of Noah’s Ark replete with different animals, protests were made by volunteer firefighters (who in recent years are no longer allowed to assist in maintaining the health and safety of the town during Carnival) and mini-tractors brought out in solidarity with the farmers who have blocked transport routes in protest against agricultural reforms largely dictated by the European Union.

In towns like Ciudad Rodrigo, a strong sense of tradition goes hand in hand with the conviction that faceless metropolitan bureaucrats are always ready to issue oppressive diktats from afar. Audiences for professional corridas and popular festivities don’t always overlap, but municipalities with the latter are less likely to face calls for prohibition, due to the integration of bulls into everyday life alongside direct benefits for the local economy.

This explains why Morante de la Puebla – arguably the 21 century’s finest matador and a campaigner for the far-right Vox political party – has organised encierros in Andalucía, a region where no such tradition exists (the Tom Cruise and Cameron Diaz 2010 star vehicle, Knight and Day, is pure fiction).

Conrado retired from the capeas of Ciudad Rodrigo in 2008 in his eighties. The so-called last bohemian amateur bullfighter was the exception rather than the rule: popular festivities are generally a young (wo)man’s game that facilitates a generational handover key to the industry’s sustainability.

The biggest existential threat posed to bullfighting is not direct prohibition, but the distinct possibility that aficionados are a dying breed. A charity bullfighting festival featuring a number of Spain’s top matadors was organised in Moralzarzal, a commuter town outside Madrid, on February 17 to raise funds for taurine surgeons.

Doctors have historically taken a pay cut for the honour of training and serving as taurine surgeons. Younger medics increasingly believe their time and talents are better served elsewhere. Much like the non-romantic fate of many bulls at the hands of second-rate matadors, the death of tauromachy will probably be a long, painful process.

For the time being, there is life in the old beast: the number of season-ticket holders at Las Ventas for the 21 corridas to be held in May and June has risen in 2024 to 16,500. Spanish citizens still buy more tickets for the national fiesta than for the theatre or for non-Hollywood films at the cinema.

To apply a 21st-century idiom to an antiquated art form, it is what it is.