Notoriously, war is a relentless factory of fog. But it can also force moments of clarity: confrontations with thorny questions that oblige you to test your first principles.

For many years now, I have been writing and speaking in support of multiculturalism and of immigration. It is also true that, since the Hamas atrocities of October 7, I have been alarmed by some of the poisonous and antisemitic rhetoric used by protesters in this country: the calls for “jihad” by Hizb-ut-Tahrir demonstrators; marchers chanting “from the river to the sea!” (a battle-cry which, if enacted, would mean the annihilation of Israel); and the distribution in Parliament Square on Saturday of pamphlets celebrating the “extraordinary heroism” of Islamist terrorists.

Cue, inevitably, a digital “gotcha” moment on social media. A sample of posts on my X feed: “I thought you said that multiculturalism was a good thing?”; “You caused all this”; “You’re a renowned advocate of open borders. Reap what you sow”; “Don’t know why you’re surprised. Import the third world, get the third world”; and (my favourite) “I thought you were a communist?”.

All of this, I feel, somewhat overstates my personal influence upon public policy. Never mind: the question cannot be ignored because these posts (I am fairly sure) reflect what some Britons will have been thinking since the rallies began. They’ll have been quietly concluding that Suella Braverman was right in September, when she said that multiculturalism “has failed because it allowed people to come to our society and live parallel lives in it”.

I think she’s wrong, and not only because I believe that diversity enriches a society and that heterogeneous communities are stronger, more rewarding to live in and better suited to the challenges of our times. I feel no more nostalgia for a supposedly monocultural Britain (that, let’s face it, never truly existed) than I do for a world without antibiotics, or the universal franchise, or refrigerators, or IMAX cinema.

For a start, multiculturalism, properly understood, is an empirical term rather than an ideological menace. We live in an age when, as the philosopher John Gray has put it, “pluralism is an historical fate”. In our hyperconnected, interdependent world, it is the default social arrangement.

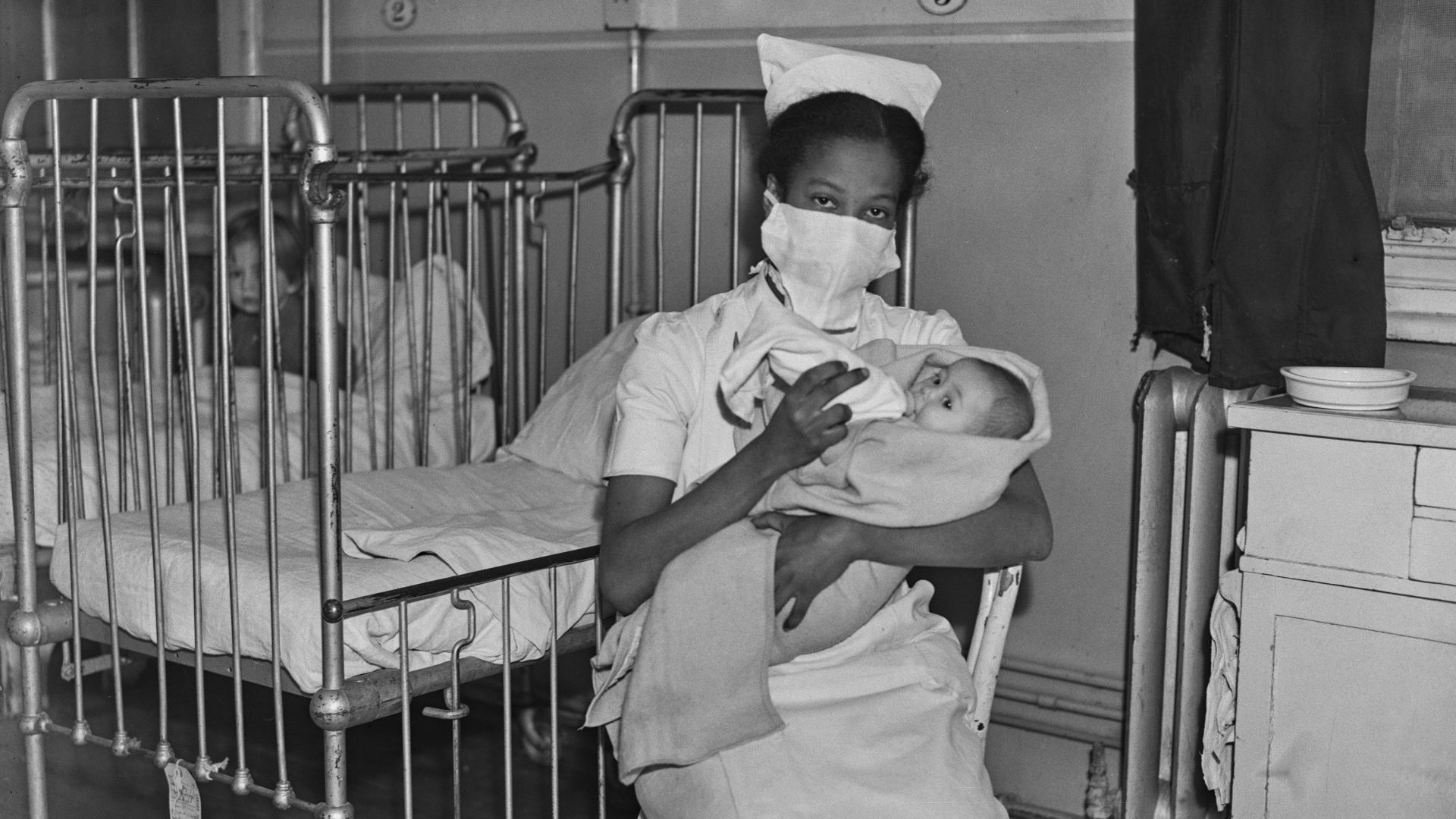

And more to the point: it is a fate that we embraced long ago. Our NHS represents not only a shared belief in free healthcare; it also enshrined, 75 years ago, a clear position on workforce mobility that, more broadly, reflects the reliance of whole sectors of the UK economy upon the contribution of immigrants.

It is sometimes objected that we were not “consulted” on any of this. To which I reply: you most certainly were, not in a referendum, but in a billion micro-decisions. Every time we insist on well-staffed public services, on social care that is minimally decent, on a service economy that functions, on the prompt delivery of our online orders, we sign up to a multicultural nation.

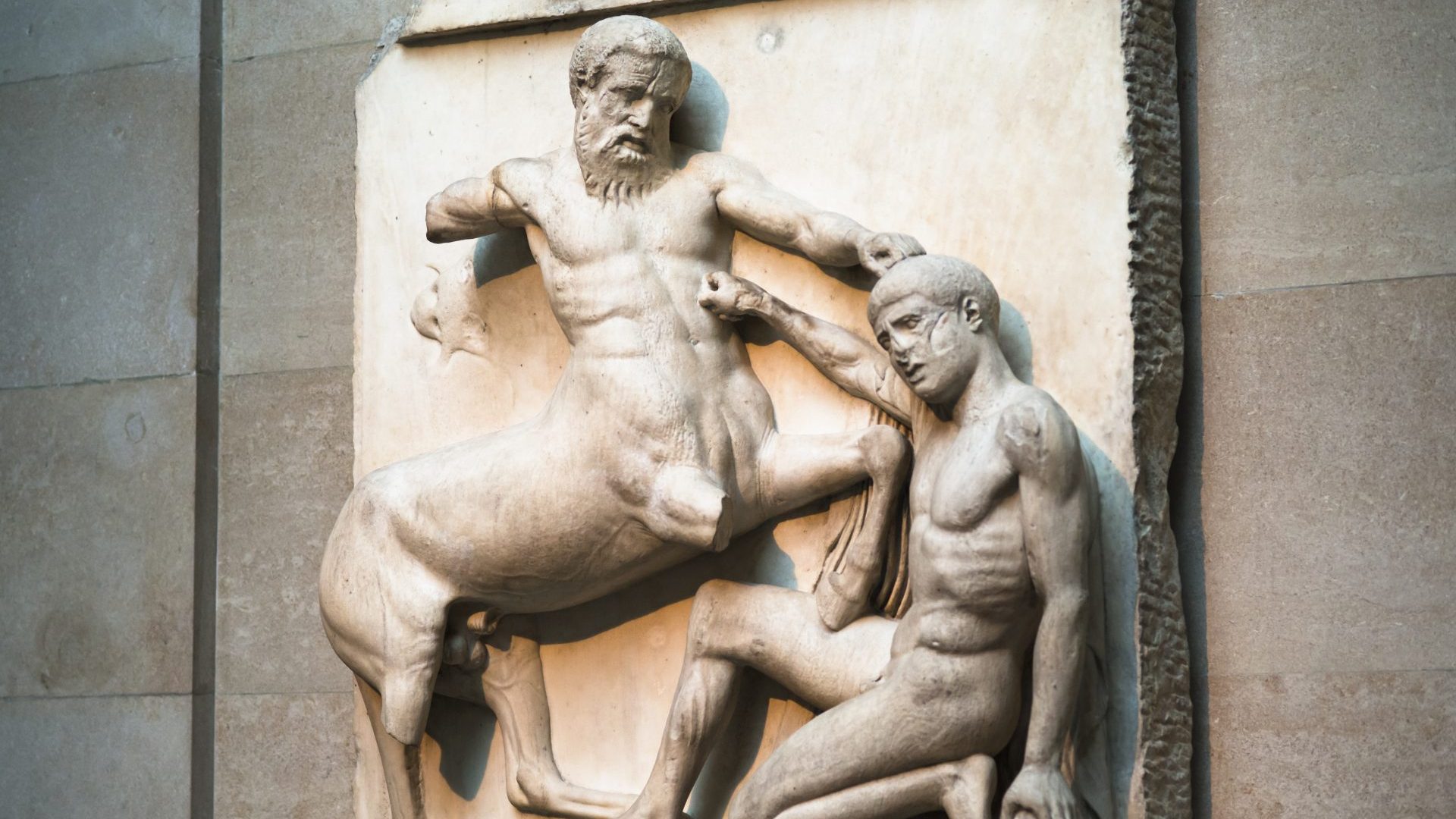

None of which is to say that diversity is without complexity or abrasion. As Isaiah Berlin, the great sage of “value pluralism”, teaches us, differences in opinion, belief and tradition are “an intrinsic, irremovable element in human life” (and were so long before the accelerated population mobility of the 21st century). At moments of historic intensity, such as the Middle East crisis, these disharmonies are amplified.

How to respond? There are two dead ends. One is the moral relativism that seeks only to avoid offence being taken by any individual or community. It appeases every protest, apologises by reflex and caves in at the merest prompt.

In a liberal society, for example, there is an inviolable right to freedom of worship. There is no right whatsoever to establish neighbourhood theocracies or to make physical threats on the basis of offended religious sensibilities. It is unconscionable that the teacher who used a caricature of Muhammad in a religious education class at Batley Grammar School in West Yorkshire in 2021 has reportedly been forced to assume a new identity and move away from the area.

The second dead end is represented by Braverman’s rhetoric, which inflames tensions without resolving them; which whips up resentment and plays the age-old, despicable game of attributing blame for every public grievance to newcomers or to those desperately trying to make it to these shores.

There are no glib answers or silver bullets in this ongoing process of negotiation. But a step forward, I believe, would be a renewed attention to the neglected concept of citizenship; to shared values and social practices beyond payment of taxes, use of public services and obedience to the law.

This is a huge subject, but to take only two examples of what can be done: there is a lot to be said for the idea of a national civic service for young people, as championed by many politicians including David Lammy, the shadow foreign secretary; and for “encounter culture” – initiatives that promote constructive dialogue between groups and generations that would otherwise have little contact.

I have also been struck by the topicality of David Brooks’s superb new book, How to Know a Person (Allen Lane), in which the New York Times columnist correctly identifies a “crisis of connection”, in which so much political activity is “about outer agitation, not inner formation”.

To know another person is to know their “social location”, he writes, and to listen deeply to what they are saying. “Wisdom isn’t knowing about physics or geography,” Brooks writes. “Wisdom is knowing about people”.

If this sounds like motherhood and apple pie, it absolutely isn’t. As Brooks puts it: “To survive, pluralistic societies require citizens who can look across difference and show the kind of understanding that is a prerequisite of trust”.

Absolutely right. In a time of war, we are once again confronted with a choice: to huddle in an angry stockade of nationalist introspection and populist resentment; or to accept and embrace the dilemmas and rewards of multicultural coexistence. I know which future I believe in.