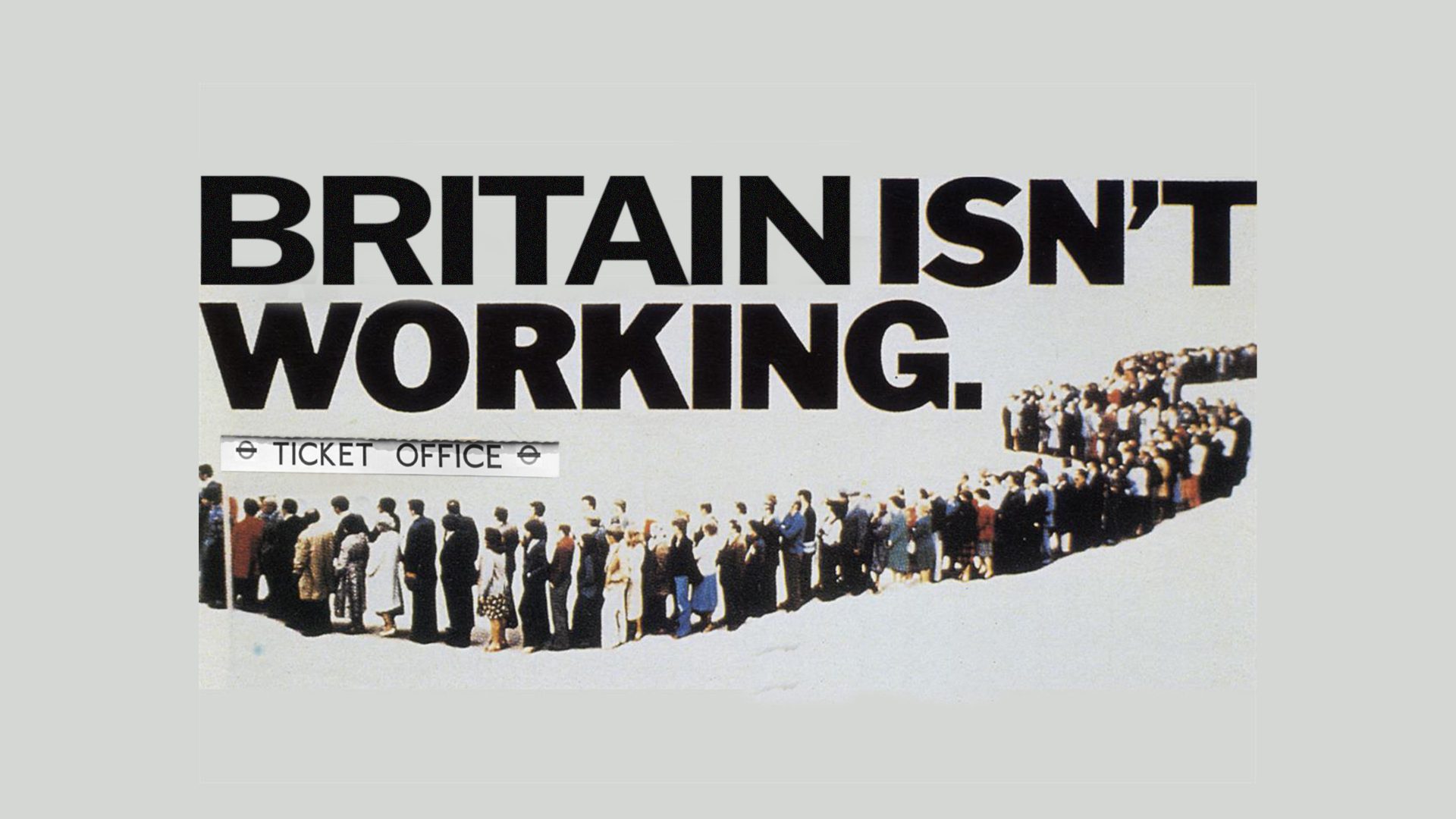

As 2022 finally limps over the finishing line, it is well to remember that this has been a year of two monarchs, three prime ministers, four chancellors, two foreign secretaries and countless other political job swaps that would not look out of place in a seasonal game of musical chairs.

It is also the year when the Conservative government went from being 4% behind Labour in the opinion polls – a manageable deficit any sensible government could hope to make up in the few years before a general election – to a 25% gap.

The year also saw the opinion polls on Brexit shift decisively on the one subject the government simply will not discuss. A kind of wilful silence has descended, even though most people can now see the problem all too clearly, a fact that is borne out in the polls. Now, only 20% of people think the government is handling Brexit well and 67% say it’s handling it badly. But will the government talk about it? Not a chance.

Considering that during that time the British government has won high praise for its support for Ukraine and its strong line on Russia, this is an amazing turnaround. It must count as one of the most radical sea changes in British political and economic history. So how did it happen?

Scandal, lies, incompetence, fantasy economics, criminal behaviour and appalling mismanagement have all played their part, but I like to think that Brexit chickens have also come home to roost.

The year began pretty much as normal. Queen Elizabeth II was still on the throne, with preparations well in hand to celebrate her Diamond Jubilee. The PM was as usual in full flow. His rambunctious act was growing stale, but he was still acting as if he was as popular as ever. Covid had been a personal triumph, Brexit had been delivered – another triumph – and his reputation was, he claimed, unstained.

But January 1 also saw the full introduction of border controls with the EU. The transition period was over and Brexit proper was upon us.

Immediately goods crossing the border between Great Britain and the EU were subject to customs checks. Border formalities started, and millions of pounds worth of goods a day were held up as officials made sure they met the relevant standards, had the right forms and were safe.

In short, a once-seamless border became one that required £7bn a year of red tape, where lorry parks had to be built and the queue on the M20 was so huge it was visible from space. This was the so-called Operation Stack. By August the government had abandoned any idea that the M20 could return to normal. It remains an on-off lorry park. Brexit was already making its mark on Britain, in the form of permanent traffic cones, speed limits and lane closures.

It would be worse but for the fact that the arch Brexiteer, Jacob Rees-Mogg, made a special trip to Dover in April to announce the fourth delay to the introduction of British checks on EU imports, a move he said would save “British businesses up to £1bn in annual costs”. Strange, but I don’t remember being told these border checks would cost British businesses anything at all, let alone a billion a year. Still, these mysterious “costs” were delayed in an attempt to stop prices rising for consumers, as fuel prices stoked inflation. It was a tacit admission that Brexit had pushed up prices. But the checks on food will have to be introduced at some point, not least to stop diseases such as swine fever entering the UK.

That was not the only border issue this year. The border down the Irish Sea, proposed, agreed and signed by one B Johnson has been a running sore, one that will doubtless continue well into 2023 and beyond. The Northern Ireland Protocol was intended to avoid a physical border on the island of Ireland, between the Republic – in the EU – and Northern Ireland – not in the EU. Instead, the border would be between mainland Britain and Northern Ireland, ie down the Irish Sea. It has always been a messy compromise, but one that Johnson’s mishandling of the Brexit negotiations made inevitable.

In February the third face-to-face meeting between the then foreign secretary, Liz Truss, and her EU counterpart, Maroš Šefčovič, about how to improve the deal, reduce checks and red tape and ease trade between NI and the mainland broke down without agreement. An increasingly threatening prime minister began suggesting that the UK would renege on the protocol, an act that would break international law. The threat has also poisoned the UK’s relationship not just with the EU but also with the White House, and the ensuing row has rumbled on all year, through three prime ministers, doing huge harm to the UK’s international reputation.

In retaliation, the EU refused UK access to the hugely important Horizon funding scheme, which is vital to the research capabilities of UK universities. Talks on agreeing data transfer standards, recognising professional qualifications and the equivalence of City regulations are also getting nowhere. The EU has no intention of letting Brexit Britain have its cake and eat it. The UK must stick to its word, or it will not be trusted.

Rishi Sunak has now decided to shelve legislation that would have allowed the UK government to tear up the protocol. Joe Biden has made it clear that he expects to see all questions on the Irish border cleared up in time for the 25th anniversary of the Good Friday Agreement, which falls on April 10 next year. He’ll be pleased Downing Street has withdrawn its provocative bill, even though Downing Street has signalled it intends to bring its proposals back at some point.

Meanwhile, in Northern Ireland, the Brexit-supporting DUP is refusing to allow the Stormont Assembly to sit. It has also made clear it will not join a government until the protocol is destroyed, meaning that Northern Ireland in effect has no parliament and no government. It’s just one of the Brexit gifts that keeps on giving.

Throughout the year the farming and fishing industries were also beginning to discover that they had been left to swing in the wind by Brexit. The fishing industry has lost out because the UK failed to negotiate access to Norwegian waters on anything like the scale we had before Brexit, while EU vessels still have access to UK waters. In addition, all those UK exports of salmon, oysters and clams to the EU now face huge amounts of red tape. Farming has discovered that the promise to give it even more money than the Common Agricultural Policy was a lie, and what money there is will go to big farms for environmental improvements; small farms will lose subsidies and therefore their profitability.

The new trade deals that Liz Truss signed in 2021 with Australia and New Zealand made things even worse. They were hailed at the time as a major benefit of Brexit, in large part by Truss herself, and ministers claimed they were part of £800bn in “new free trade deals”, a figure now rubbished by the official statistics watchdog.

In fact, these deals gave away far too much for far too little. They allow the gradual reduction of tariffs and quotas on imported food, but this has virtually no discernible benefit for the British economy. What it does do, however, is put British agriculture under intense cost pressure as cheaper food is imported from the other side of the world.

It was only in November that a Tory finally spoke the truth. George Eustice, a former environment secretary, explained in detail to the Commons what a terrible deal Truss had negotiated. “The first step,” he said, “is to recognise that the Australia trade deal is not actually a very good deal for the UK, which was not for lack of trying on my part.”

Johnson had hailed the deals as a “new dawn”. But it turned out that Truss’s negotiating strategy had simply been to ask the Australian delegation what they wanted and then offer it to them. It is hard to avoid the conclusion that what Truss actually wanted was to cut a quick deal to make herself look good. New Zealand’s foreign correspondents were left incredulous that Britain should negotiate such a damaging agreement.

Interestingly, the one deal Truss did sign that was a slight improvement on the one the EU had was with Japan. However, this year we also discovered that, as a result of that deal, trade with Japan was in fact declining. The apparent contradiction is explained quite simply – Japanese companies used to base their European headquarters in the UK. They like London, they like the schools and the shops and the sport but most of all they liked that until Brexit, the UK was part of the EU’s single market.

Now it seems that the joys of London are not enough to keep Japanese HQs here when there is a border between them and their factories on the continent. As a result, they have quietly moved to the EU. The money from their European operations now goes through Paris or Amsterdam. The trade deal was not enough to offset the costs of Brexit to Japanese businesses.

It is a pity that these details did not emerge until long after Johnson was finally thrown on his sword (in July) and after Truss got the top job by promising the impossible to Brexit true believers. Because as the year progressed, the damage to almost every sector of the economy became increasingly apparent, while at the same time the inability of the true believers to see what was happening before their eyes got even more acute.

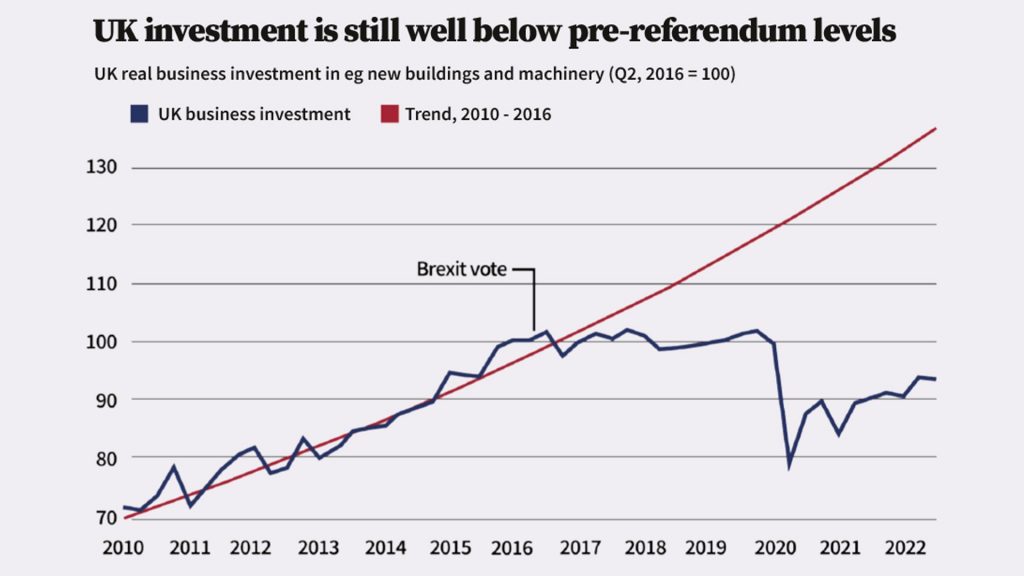

The fate of manufacturing alone should have been enough to open their eyes. The sector most affected by Brexit, it has been ripped from the European supply chain. That is significant, because British manufacturers produce 45% of all UK exports and fund 65% of all private UK research and development. The industry also receives substantial foreign investment, with the foreign firms usually being the most efficient and productive. Research by Make UK, the trade body for British industry, reached some worrying conclusions. Its findings, published in the summer, found that investment by continental firms at their UK plants is now half that of UK firms. The figures suggest that EU firms are running down UK factories, or using them to supply just UK, not EU, demand.

This has been enough to worry even the few friends we have left in the EU. In November, the German ambassador to the UK tweeted: “UK is Germany’s third export market, but we are concerned that trade between has continuously declined since the Brexit referendum. Britain has traditionally been Germany’s fifth-largest trading partner. In 2022, UK will drop out of the list of the top 10.”

The appalling damage Brexit has done to the UK’s trade seems to be invisible to the British government. Meanwhile, the rest of the world is watching our slow car crash with its head in its hands. Germany now attracts more Japanese firms than the UK, and France is beginning to overtake the UK as the preferred site for inward investment in Europe. These things matter.

The UK government has made things worse by creating new UK bodies to regulate chemicals and oversee production standards, something the EU has done very effectively for years. It also means British manufacturers must now comply with both EU and UK rules. It also means many EU firms will just stop supplying the UK market. Re-testing every product and then producing to different standards just for the British market is not worth it.

There was a collective sigh of relief in November when Grant Shapps once again delayed the UK’s new product safety mark, UKCA, for a further two years. It will come into force in 2025, even though British industry would like nothing better than for it to be quietly strangled at birth.

Meanwhile Britain’s trade deficit in goods is getting wider. The current account deficit was 2% of GDP in 2021, and so far this year it has averaged 6.3%, with little sign of improvement. This figure alone shows the idea of Global Britain to be a delusion. There are no fresh, easily available markets out there to offset the loss of seamless access to the European Economic Area – 2022 has made that clear.

It was also a year of shocks for the economic darling of the Tory Party: the City. Financial services were and are one of the industries the UK is good at. The City is the financial capital of Europe and that hegemony is unlikely to be seriously challenged for a long time. But the gradual erosion of its power and influence has already started. The latest research for The City UK by EY shows its lead over other European countries has narrowed. France is coming up fast on the inside, snaffling up jobs, money and trade from London.

Amsterdam has also taken business from the City and this year it became Europe’s top share-trading venue. When the UK left the EU, euro denominated share trading by EU investors had to stop in Britain. Amsterdam simply snapped it all up.

Just this month Brussels drafted new proposals that will mean a proportion of derivative deals must go through EU clearing houses. In 2020 London handled 90% of this business, but it is under threat. The new legislation allows London to keep serving customers in the EU until 2025. The EU is using that time to build up its financial infrastructure and then transfer the business wholesale to the continent.

Other service sectors beyond the City also found 2022 a tough year. Many professionals have lost the right to travel and work unhindered across the EU. They need visas, which are handed out by individual countries, and business travellers now need carnets itemising all their equipment, which have to be checked at the border when leaving and returning. Touring musicians have to use EU-based transport – yet more sand in the machine. It’s no wonder workers with an EU passport are increasingly attractive to employers in the UK, as they face none of these problems.

And then there’s immigration. Nearly every company, business organisation and economist I have spoken to this year has complained that limiting immigration to the UK is a huge act of economic self-harm. This year tens of millions of pounds’ worth of crops rotted in the fields because there were no seasonal workers for the harvest. The construction industry is short of skilled workers in virtually every trade. A shortage of HGV drivers is threatening supply chains. Almost every bar, café and restaurant has an advert for staff in its window. Industry after industry has begged the government for more seasonal workers, for exceptions to the rules on qualifications and English-language tests, for a reduction in the pay level necessary to qualify for inclusion in the immigration scheme. Most, if not all, have been snubbed.

The hospitality industry believes that worker shortages have cost it £20bn in revenues this year, which corresponds to £7bn in lost taxes for the exchequer. The government’s response has been a combination of silence, patronising lectures to industry on where to find the staff and a complete panic over asylum seekers. That panic has been so bad that, earlier this year, the government seemed to be seriously suggesting that foreign students should be stopped from studying at UK universities.

A better way of undermining one of our largest export industries, education, would be hard to find. The move would quite possibly bankrupt several universities and certainly limit the number of places available for British students, who are subsidised by foreign students’ higher fees. The farcical nature of this obsession is best illustrated by the fact that the latest chancellor, Jeremy Hunt, had to promise the Office for Budget Responsibility that the government would allow more workers into the UK before the OBR would approve his autumn statement.

That budget in all but name was forced on the government after Truss and Kwasi Kwarteng crashed the pound, the bond market, the mortgage market and the pensions industry all in one go. They were attempting to introduce just the kind of budget that their party’s Brexit ultras had been craving for years. The situation was only saved by the intervention of the Bank of England.

The Brexit fantasy was that growth would flow from tax reductions for millionaires funded by borrowing, and by unspecified cuts to red tape and regulations. The transition to a “Singapore-on-Thames” economic model was decades in the planning and for the European Research Group it was the ultimate reason for Brexit. It lasted a week. To try to reverse at least some of the damage, Hunt had to raise taxes for years to come – but even with these hikes, there is still not enough money for nurses or ambulance drivers, social care or defence.

Truss’s mad Brexit budget was hopefully the last act of self-harm this year, because 2022 has been a disaster. We’ve had worse trade, more red tape and lower investment. Sector after sector has been hit by Brexit, and squeezed by U-turns on legislation, border checks and standards, pointless threats over the NI Protocol, a run on the pound and staff shortages.

Throughout the year the picture has become clearer to anyone who is willing to see. The UK is now heading into a prolonged recession and is the only country in the G7 not to have recovered economically after Covid.

It all amounts to one thing; 2022 will go down as the year when Brexit made the UK once again “the sick man of Europe”. Will the government ever admit it? Will the opposition even mention it? Don’t hold your breath.