Brexit supporters have been lucky – if you can call it luck. Covid and the war in Ukraine have come along at just the right time (for them) to help mask the terrible effects of Brexit.

But now we are able to separate the effect of those twin disasters from other underlying problems faced by Britain. As a result, the deep, painful, and avoidable damage that Brexit has done and will continue to do to the British economy is now becoming clearer. Brexit has added red tape. It has reduced trade. It has choked off business investment. It has delivered increased inflation.

Now the consequences of ending free movement of people between Britain and the EU are also becoming clear.

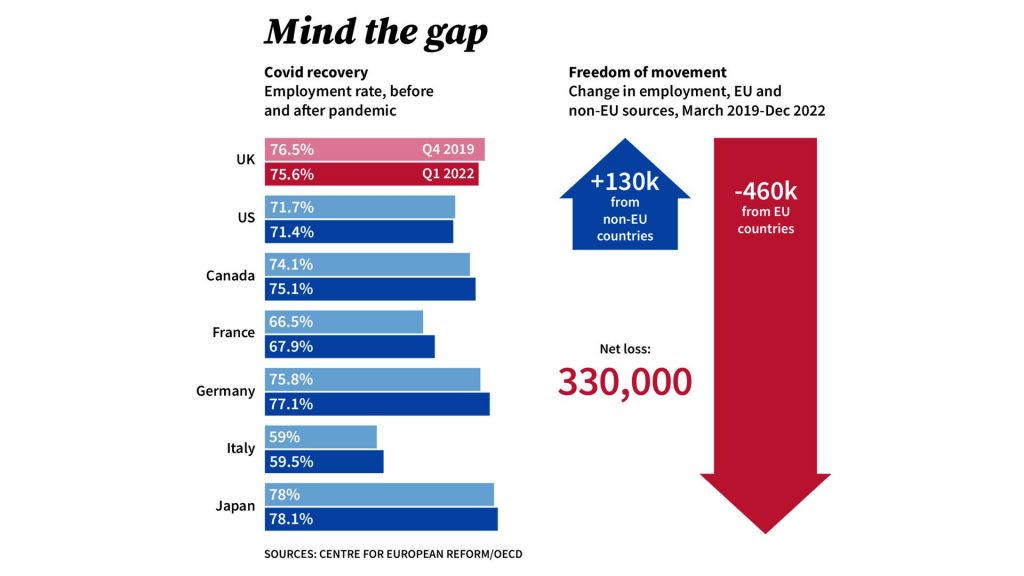

The latest analysis conducted jointly by two UK-based thinktanks, the Centre for European Reform and The UK in a Changing Europe, brings into sharp focus Brexit’s effect on the UK workforce. The research, led by John Springford at the London School of Economics and Jonathan Portes, professor of economics and public policy at King’s College London, finds that Brexit has reduced the UK’s workforce by 330,000 people, the equivalent of 1% of the total.

The figure is simply the increase in new immigration from outside the EU post Brexit minus the fall in immigration from the EU after the end of free movement. The UK lost 460,000 staff from the EU but brought in another 130,000 from elsewhere, leaving a net loss of 330,000 (see chart).

Since immigration almost inevitably means higher economic growth, the consequences will be felt across the country; quite simply, this makes us poorer. There are 330,000 people who should be working right now in the British economy, but who are not. They are not living here, renting here, spending in the shops here or paying taxes here. It represents a substantial loss to the economy, to the country’s wealth and to the government’s revenue.

But what is the government’s response?

Well, of course, its instinctive reaction is to promise to cut immigration even further. That is, after all, what its Brexit-supporting core membership wants and what it expected from Brexit – less immigration. To them, it doesn’t matter that the government and its economic experts know full well that cutting immigration even further will damage the economy even more. The frothing europhobes, closet racists and swivel-eyed loons have to be fed, and in consequence, the rest of the country has to suffer.

That is why the government has already set minimum salary thresholds which immigrants must achieve, in order to be given a visa. It’s also why there’s an English language test and an “immigration health surcharge”, which is essentially a tax on visa-holders. It is almost as if they don’t really want people to come to Britain and do the jobs that desperately need doing.

Compare that to what used to happen: the UK had smooth and seamless access to hundreds of millions of fellow Europeans. Companies had no hurdles to overcome, no forms to fill in, no extra costs to bear and no interference from government. John Springford, who conducted the research at the Centre for European Reform, told me: “Overall, combining the end of free movement with this new immigration system has made the UK labour market more closed”. The consequences of changing to a more isolated and closed economy have been inevitable and painful.

This research highlights the scale of the problem very clearly. Although the 330,000 total is just 1% of the workforce, the pain is not evenly distributed across the economy’s different sectors, as the following list of worker shortfalls shows:

• Transportation and storage: 128,000, which is around 8% of total employment in that sector

• Wholesale and retail: 103,000 – 3% of the sector

• Accommodation and food: 67,000 – 4% of the sector

• Manufacturing: 47,000 – 2% of the sector.

And it is not as if the government is unaware of what is happening. After all, the logistics and transport sectors have been pleading for years with both the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (Beis), and the Department for Transport to relax the rules to help them bring in more workers. As Rod McKenzie, executive director of policy at the Road Haulage Association, puts it: “We are still short of 50,000 drivers, but have recruited many Brits to drive trucks. Our big worry is in the mechanics and fitters trade – where a serious shortage is now worsening – which is a worry for truck maintenance.”

Farming and food processing have likewise been begging the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food for special exemptions to the new stringent immigration criteria, so that crops are no longer left rotting in the fields. The construction industry and engineering sectors are making the same argument. As Jamie Cater, senior policy manager at Make UK, the manufacturing industry’s trade body explains: “There are currently 78,000 manufacturing vacancies across the UK with many companies saying that key roles are remaining unfilled for 12 months at a time. Manufacturers are increasingly unable to find the technically skilled workers they need in the domestic labour force. To address this issue, we are asking the government to ensure that the long-promised review of the shortage occupation list begins urgently.”

At the same time, the health secretary knows full well that hospitals and care homes are crying out for more staff to make up for the terrible shortages that affect the health of the whole country.

The Treasury is being lobbied incessantly by every sector from accountancy to zoo keeping for help.

The problem, then, is not the result of ignorance. There is a scheme to allow more people into areas where there is a shortage of workers, but the government has been almost entirely deaf to requests to expand that list, as Make UK has said. The new points-based regime is just not bringing in enough workers.

The government has simply set the criteria for new immigration extremely tightly, in order to reduce it, whatever the economic damage. It is hard to think of another time when the government has set out to deliberately damage the economy, but this is what it is doing now.

It has also been hit by an underlying trend that makes the whole situation worse – the Great Retirement.

Since Covid, the British workforce has shrunk by 500,000, and no one is sure why. Many people seem to have discovered that they quite like being at home a lot, that they don’t need quite as much money as they thought and that there is more to life than working full time. There is also the effect of long Covid, which affects a significant proportion of people, especially those with underlying health problems, as well as the huge NHS waiting list, which means ill workers are taking longer to get back to work than they should. As a result, the UK is the only member of the G7 whose employment rate in the third quarter of 2022 was lower than its pre-pandemic level.

All in all, it is a severe shock for the economy, one that, in the past, we might have been able to reduce by the free flow of eager workers from across the EU. But not any more. As John Springford observes, the obvious response from industry will be a combination of higher wages, higher prices, and lower output. Lower immigration therefore means a smaller economy.

At a time when the government claims its ambitions are to keep down pay rises, reduce inflation and grow the economy, this is an act of self-harm that works directly against No 10’s stated aims. It is also worth remembering that Sunak is promising to bring down immigration even further.

The real motive for this Tory government is obvious. It knows full well that ramping up the fear of immigration is a vote winner. The result is its panic over small boats in the Channel, its shameful Rwandan policy and this blind indifference to the economic damage caused by its immigration policy.

The honest thing to do would be to tell voters that the UK needs more workers, it needs more immigration, and it needs more of the economic activity that these immigrant workers create. But that would require an honest government, one that is not pandering to the hard right and one that puts the country’s interests first.

Dream on.