Suzanne Moore on three writers grappling with the restlessness that comes with advancing years and who are interested in living fully, not contentedly.

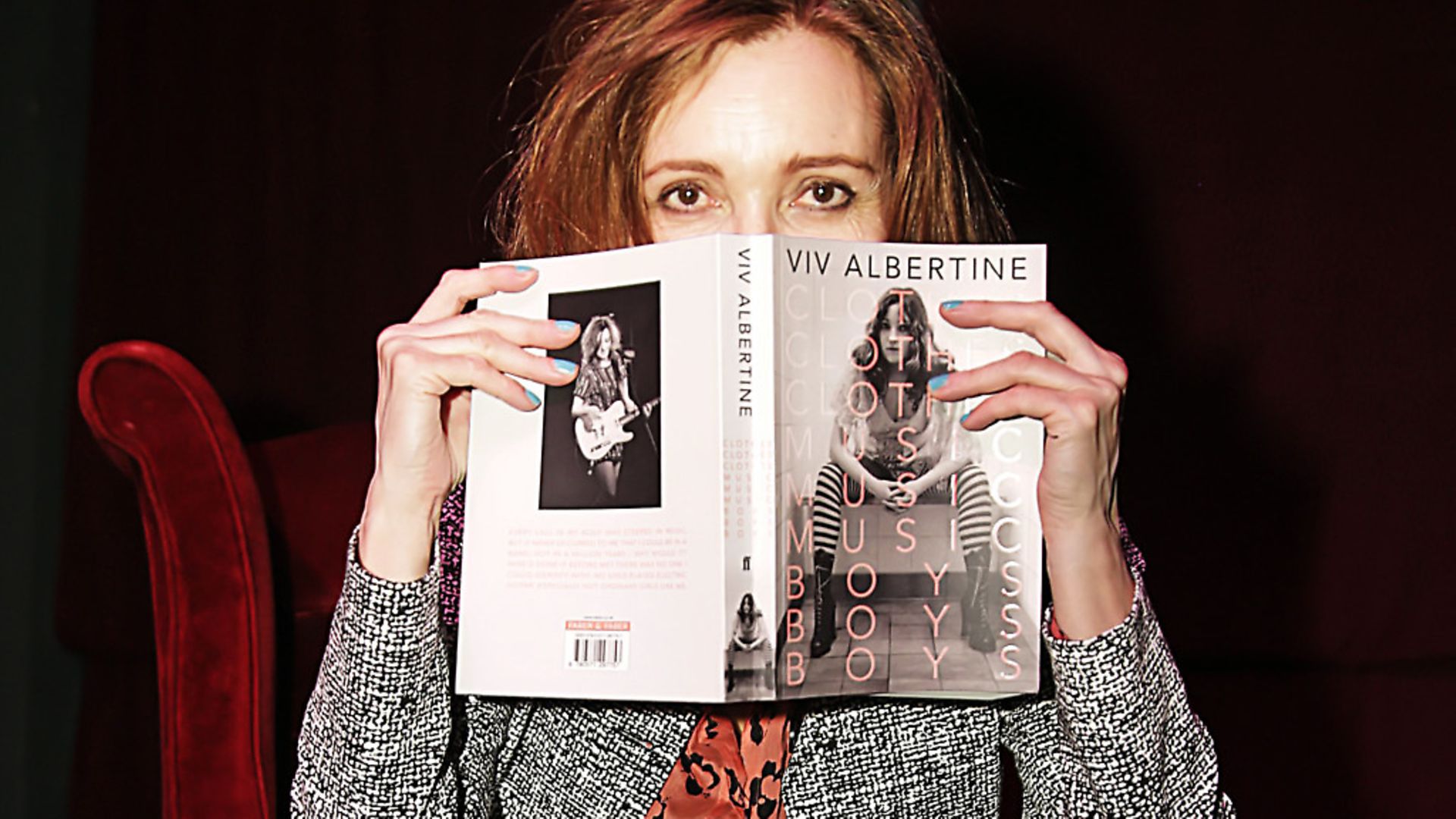

Recently I went to see Viv Albertine read from her new book To Throw Away Unopened. She started by saying she wakes up every day feeling murderous. There is a woman after my own heart. Don’t give me mindfulness and gratitude. Don’t give me the uniform punk nostalgia that amounts to a nicely corseted Westwood dress and feeling sad about Joe Strummer. Give me ex-Slit Albertine radiating unease, difficulty, honesty.

This is punk but it is something much more. Here is a woman in her 60s talking about what that’s like. How was she formed, she asks in the book, as she looks at her parents’ life and her mother’s death. She fought off the dogmas of capitalism and patriarchy and respect for authority. ‘How come I fell at the last fence and impaled myself on the railings of romance?’ she asks.

With self-lacerating honesty she talks of the failings of the female body; when it won’t reproduce (she had 11 rounds of IVF treatment before her daughter was born; when it gets ill (she had cancer); when it is no longer considered desirable. To be an older woman is to be a failure. You are not dead but you have no real purpose to serve if you no longer fit the specifications of the male gaze. Well that’s one way to see it.

Another is that this is a time of immense possibility for women and such stories of my generation show our lives in glorious complexity. Here we are, no longer having to pay lip service to what we were meant to be. We have had partners, children and careers. Whatever. And it’s not enough. It’s never enough.

There is a great wanting, still. For what, it’s not always clear. Albertine goes on a series of bloody awful dates. Men her age can barely get it up, or prefer much younger women. The hysterical efforts she makes in ridding herself of every body hair and sorting out the soundtracks of the dirty weekends – a woman’s work indeed – result in serial disappointment. She would rather be alone. What she wondered the other night was when people will stop asking her if she has met any nice men recently. She is 63.

Deborah Levy – simply one of our best writers – whizzes around on her electric bike, her marriage broken, also wondering what it is to be a woman and have a creative life. Her mother is dying. Did she underestimate her mother’s dreams? Albertine’s mother is proud of her daughter’s rebellion and primed her for it. Levy is dismantling the family home, settling her daughters into a new smaller flat. No longer wife but still mother, she looks with clear-eyed intelligence to De Beauvoir, and De Beauvoir is not really there for women like us somehow. Magnificent, yes, but De Beauvoir chose not to have children and old age, for her, was nothing but terrifying. She wrote her book Old Age in her early 60s. Old age ‘kept catching my eye from the depths of the mirror. I was paralysed sometimes as I saw it making its way toward me so steadily when nothing inside me was ready for it,’ she wrote.

In The Cost of Living Levy is asking if she can be a sexual being, a mother, a writer. If she can be herself at all, now interrogating what that self means. Albertine scraps, she physically fights. She is used to violence. As she said of The Slits, men didn’t know whether they wanted to f**k then or kill them. When some middle-aged men talk all through her gig, she gets off stage and throws their beer over them, slowly, in a golden arc. She is unafraid.

Levy also wonders about risk – ‘to separate from love is to live a risk-free life’. She takes risks. She is breaking up the family home but what is she now making? At a time when everything should be predictable and settled for many women, it can be less so.

My god I love these difficult women, fearless in their complexity. The existential crisis of middle aged women is being spoken as the older stories are ripped up or found lacking. They are seeking new ways of living because the cost of the old ways is too high. They seek to maintain themselves, alive with rage and ambivalence as they come into the light. This is not the invisibility of the middle aged. These are shimmering homecomings.

Lara Feigel wants also to be free. She too knows the ways in which women are said to be fulfilled and, in Free Woman, returns to another pioneer for guidance – Doris Lessing. Lessing left her children, she pursued liberation not equality. Anna Wulf, the protagonist of The Golden Notebook is nowadays a difficult heroine, who wants to give herself to a ‘real man’ in bed completely but not be identified as a wife. As Feigel writes, ‘Lessing placed sexual fulfilment at the centre of women’s lives, while at the same time insisting on the urgency of their need to distance themselves from the expectations created by their sexual roles’.

Here we have it. Can we have it all? And is all even what we want? These memoirs matter because they ask how love matters, and how its power passes between mothers and children, and how romantic love leaves so much to be desired. What is the selfhood desired beyond it? Are we even allowed to name it? This restlessness that comes mid-life comes even to those who have lived up to society’s expectations. We do what we are told will make us happy and yet…. it feels not settled down but settling for less.

These women are interested in living fully, not peacefully, not contentedly. The myths crumble in their hands and they are unafraid of chaos. They are angry, stunning, funny and questioning. This is the revolt of women who some think don’t matter any more. They matter more than they ever have.

Levy describes her new life as being like fumbling for keys in the dark. I see these women as pushing the doors open so that we may glimpse another way of being whoever – at this stage of our lives – we may actually be.

For ourselves.

To Throw Away Unopened, by Viv Albertine (Faber), The Cost of Living, by Deborah Levy (Penguin), Free Woman, by Lara Feigel (Bloomsbury)