Is it ever acceptable to define a woman’s work by her husband? Afua Hirsch discusses the issue of society deciding a woman’s role and what they can do with their bodies.

This was the week we all learned a new Irish phrase – Tiocfaidh ár mná – or, in English, ‘here come our women’. Has the media ever given so much airtime to the voices of Irish women as in the last few days? The coverage began with the simple act of Irish people returning from the diaspora to cast their vote in a referendum on whether the Eighth Amendment to the Irish Constitution – which bans abortion – should be repealed. The world’s media documented the so-called #HomeToVote movement, predicted a win for the repeal, and took in what turned out to be a resounding victory, as the measure was overturned by a landslide.

It was, above all, a women’s landslide. The referendum results showed that it was young women across every region, across class groups, across the rural / urban divide – who rejected a measure that had denied women a choice over her pregnancy. They were inspired in no small part by the stories of women who had been suffering in silence – an estimated nine Irish women a day travelling to Great Britain for abortions, while four a day were reported to have been buying abortion pills over the internet without medical supervision, risking a jail term of up to 14 years. The story most iconic story of all in the media, perhaps, was that of Savita Halappanavar, the Indian dentist who was refused an abortion in a Galway hospital because she had a foetal heartbeat, until she died of sepsis.

The speed of social change in Ireland – a country that only legalised divorce in 1995, but then became the first country in the world to legalise gay marriage by popular vote three years ago, has been well documented. Less so the deeper questions of gender-based interests that emerged from the campaign. Before the vote, polls found that while the majority of men favoured legalising abortion, they did so by a narrower margin than female voters. Men were mobilised by campaigns on both sides, and male celebrities were lined up in support of the cause. Some, however, said it should have been an all-women vote.

The idea of allowing only women to decide a fundamental issue of women’s rights goes to the heart of the complexity surrounding issues like abortion, and their framing in the media. There have been sustained efforts to communicate the fact that equality, feminism and women’s rights are not just issues ‘for women’, but about which all of society should be concerned. At the same time, repeal campaigners emphasised their critique of existing abortion laws – the idea that a woman’s body is a vessel for pregnancy, the wellbeing of her foetus placed above her own autonomy. Giving men a vote, some argued, reinforced the idea that all of society had a stake in what women choose to do – an issue which should properly belong to them.

In the end, Irish men contributed to an unforeseen landslide vote for the repeal movement. Legislation allowing women to choose abortion freely within the first 12 weeks of pregnancy is expected to follow soon. The deeper question about women’s bodies and who gets a say over them, however, will take much longer to resolve.

I was surprised to find a piece in the Sun newspaper this week devoted to the vexed question of who my husband is.

The paper later removed the reference when I pointed out on social media that I’m not actually married, although I do have a partner. The Sun claimed ‘I don’t talk much about it’, when in fact a sizeable part of my book Brit(ish) is devoted to exploring what I have learned about race and class from my relationship. It’s a further reminder of how husbands are of superficial interest – as a form of gossip – rather than what’s actually interesting about our relationships, which is how they shape us as people and professionals.

Is it ever acceptable to headline a piece about someone’s work based on who they are married to? I doubt it, but if so, a far more interesting question would be about their division of labour and the role that plays. I was reminded this week about the fascinating journey QC Dinah Rose has been on in this respect – one of the most successful women at the bar, she once told student barristers that her best advice was to ‘Marry a house-husband! A 1950’s-style wife – someone to have dinner on the table!’ But she later reversed that guidance, changing her focus to the problem of ‘unequal sharing of caring responsibilities’.

‘Marrying a male barrister is a disaster,’ Rose had said. ‘They’ll always think that their cases are more important than yours and they’ll earn too much money and persuade you to give it up or go part-time’. I wish there were fewer column inches wasted exploring who our husbands are, and more on the role they play – for those who have one – in facilitating our work.

The Harvey Weinstein of Parliament, or a persecuted friend of equality? House speaker John Bercow is once again in the midst of a row about sexism and bullying, that is about just about everything other than the real question of sexism and bullying. The latest row centres on comments Bercow admits having made as a muttered aside, referring to the conduct of Conservative minister Andrea Leadsom with the words ‘stupid woman’. There is perhaps an interesting conversation to be had about the extent to which this constitutes sexist abuse. We have seen time and time again how gender can be weaponised against women in the boys’ school debating club atmosphere of the House of Commons, with remarks that are sometimes offensive more for their context than their content. David Cameron memorably telling shadow minister Angela Eagle to ‘calm down dear’, for example.

But that’s not the conversation being had. Controversy over Bercow’s remarks have in fact served as a proxy for more serious allegations of bullying. Angus Sinclair, a former private secretary, alleges Bercow subjected him to bullying, abuse, and angry outbursts, while his successor Kate Emms was described as having post traumatic stress disorder after performing the role. It’s all being linked – rightly – to wider concern about the culture at Westminster, claims that are now the subject of an inquiry, although one that will not investigate individual cases or reopen past complaints.

It’s a difficult circle to square for an institution that creates the protections for people – statistically more likely to be women – experiencing bullying, harassment and abuse elsewhere in society.

Bercow’s case is a complex one. It’s true that Conservatives on the right – not generally known for their commitment to feminism – have always sought to bring the liberal Bercow down. It’s especially ironic to see James Duddridge – a keen supporter of Donald Trump – leading the charge against him. Meanwhile Leadsom, who did not report the ‘stupid woman” comments herself, attracted the ire of many feminists herself when she invoked the fact that she was a mother against Theresa May during leadership debates.

The media of course recycled that old controversy, but in this case, it was a distraction.

A woman’s past conduct doesn’t exempt her from the right to be treated respectfully. Nor should otherwise liberal politics absolve a man from blame.

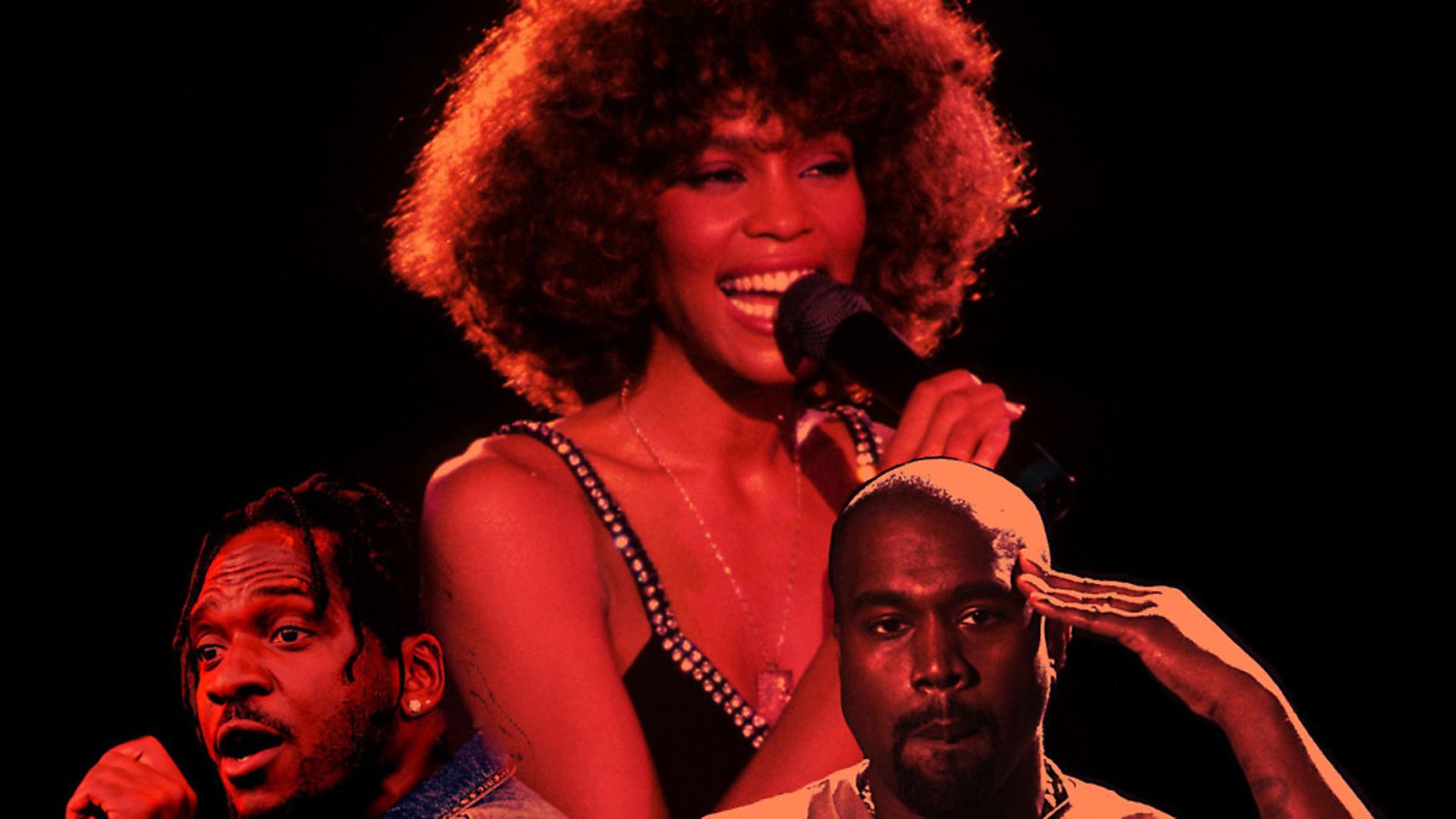

It was almost impossible to imagine just a few short weeks ago, but Kanye West has managed to sink to a new low. This week the rapper tweeted cover art for a new album by Pusha T, an artist he produces, revealing a 2006 image of Whitney Houston’s bathroom after an alleged drug binge.

The photo, for which West reportedly paid $85,000, is a squalid and miserable scene of drug paraphernalia, with connotations of the death that was to come, when in 2012 she drowned, also in a bathroom, after a coronary failure linked to cocaine consumption. There’s something tragically dark about this new link between two of the most tormented talents in music, Houston – who was never able to overcome her demons – and West, who seems at the increasingly unpredictable grip of his.

But the idea that an image of Houston’s intimate space at her vulnerable, soon-to-be-fatal low could be some kind of commercial investment is especially depressing. It’s one man profiting from a woman’s suffering, and as the writer Candice Carty-Williams put it, an example of ‘black men capitalising on the ruin of a black woman whose level of talent and fame will forever be out of their reach’.