How lost trust in once-mighty institutions created opportunities for populism

‘People in this country have had enough of experts’: the assertion was striking not only because of its audacity, but because of the person making it. Michael Gove, the then Justice Secretary, was one of the most intellectual members of David Cameron’s Cabinet, formidably articulate, cultured and erudite. Of all the senior champions of

Brexit, he was the last one would have expected to attack ‘experts’. But this was precisely what he did in a question and answer session on the EU referendum broadcast by Sky News on 3 June 2016.

Months after the vote was won, Gove would tell the BBC’s Andrew Marr that the reports of his remark had been ‘unfair’, that it was ‘manifestly nonsense’ to suggest that all experts were wrong, and that he had been referring to ‘a sub-class of experts, particularly economists, pollsters, social scientists, who really do need to reflect on some of the mistakes that they’ve made in the same way as a politician I’ve reflected on some of the mistakes that I’ve made.’

Entitled as he was to offer this ex post facto clarification, Gove’s original attack had been – as he surely knew – politically canny. It tapped into a seam of distrust that was essential to Leave’s victory; a growing suspicion that traditional sources of authority and information were unreliable, self-interested or even downright fraudulent. The Brussels elite was not the only hierarchy or institution against which Britons rose up in anger in the referendum.

This collapse of trust is the social basis of the Post-Truth era: all else flows from this single, poisonous source. To put it another way, all successful societies rely upon a relatively high degree of honesty to preserve order, uphold the law, hold the powerful to account and generate prosperity. As Francis Fukuyama observes in his book Trust, the social capital that accrues when citizens cooperate sincerely and scrupulously translates into economic success and lowers the cost of litigation, regulation and contractual enforcement.

Beyond the commercial sphere, trust is an essential human survival mechanism, the basis of co-existence that permits any human relationship, from marriage to a complex society, to work with any degree of success. A community without trust ultimately becomes no more than an atomised collection of individuals, trembling in their stockades.

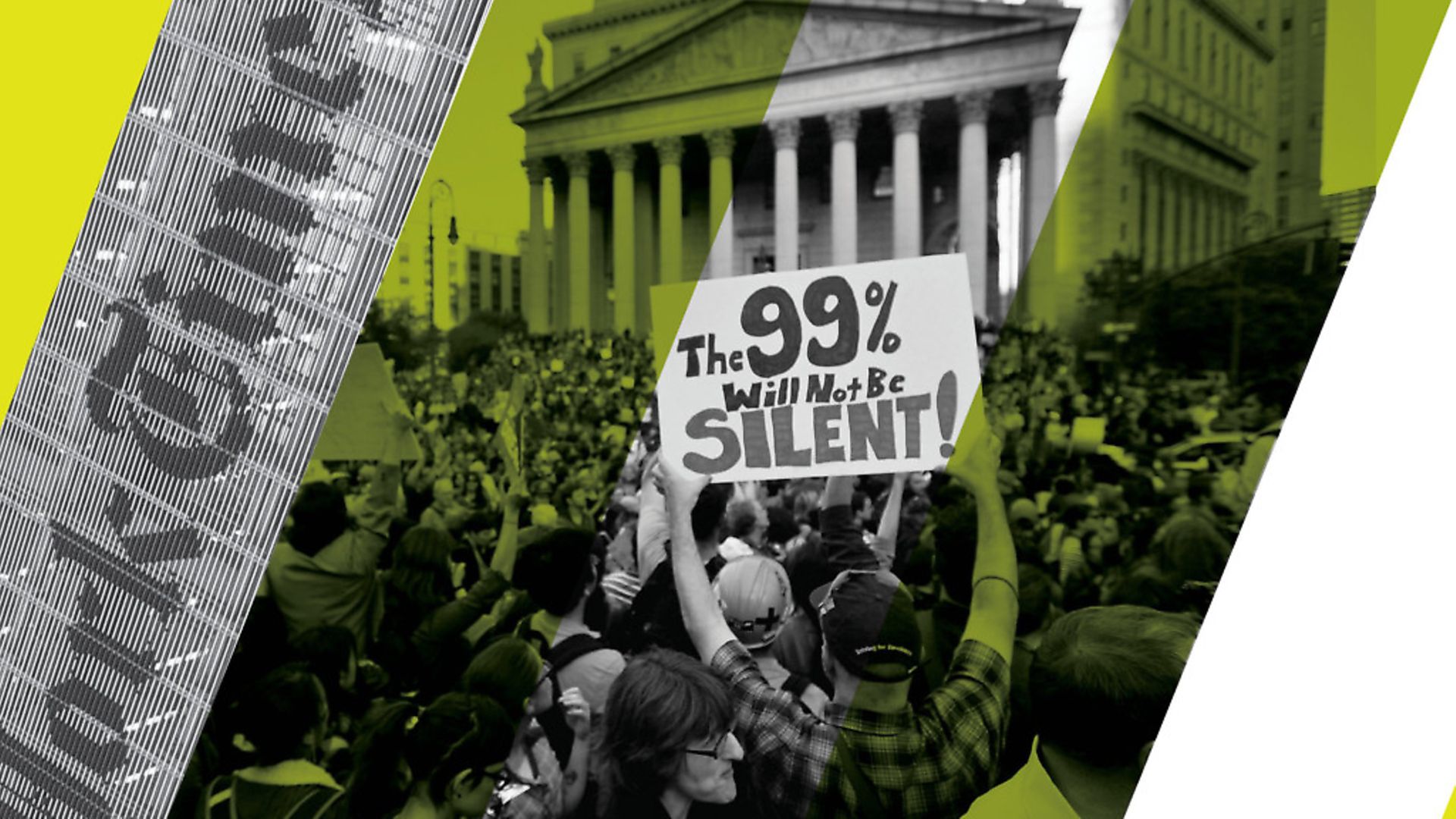

Yet that is precisely the trajectory upon which the world has been embarked in recent decades, as an unrelenting series of storms have conspired to deplete what reserves of trust remain. The financial crisis of 2008 took the global economy to the brink of meltdown, averted only by eye-wateringly huge state bailouts for the very banks that were responsible for the disastrous collapse. Occupy Wall Street was only the most visible manifestation of a much broader disgust that some institutions were evidently ‘too big too fail’, while ordinary people paid the price in the subsequent recession and cuts to public services imposed by deficit-conscious governments.

Hostility to the globalised economy shifted from the fringes to the centre of political discourse.

In Britain, the financial crisis was followed by the humiliation of the political class in the 2009 parliamentary expenses scandal. In a series of remarkable articles, the Daily Telegraph exposed the sharp practices that enabled MPs to supplement their official salary by charging the taxpayer for everything from moat-clearing and a £1,600 duckhouse to a bath plug and pornographic films.

Politicians had long been objects of suspicion. But the allegations of ‘sleaze’ against the Conservatives in the nineties and the charge that the Labour government of 1997–2010 was all ‘spin’ and no substance were but a dry run for this extraordinary national spectacle – part-comedy, part-tragedy.

In 1986, only 38% said that they trusted governments ‘to place the needs of the nation above the interests of their own political party’. By 2014 that figure had fallen to about 18%. The rot was now threatening the whole democratic process.

Meanwhile, scandals in show business – especially the monstrous sexual crimes of Jimmy Savile – have dragged the BBC and other institutions through the mire.

Without hyperbole, the broadcaster’s much-admired World Affairs Editor, John Simpson, described the Savile affair as the BBC’s ‘worst crisis’ in fifty years. As became horribly clear, the late Top of the Pops presenter had been the beneficiary of a culture of institutional neglect: blind eyes were turned, inquiries were token, shoulders were shrugged. Paradoxically, Savile’s access to Broadmoor secure hospital and Duncroft Approved School for Girls was seen as evidence of his charitable instinct rather than something truly ghastly. Savile was certainly protected by stardom and his notorious readiness to threaten litigation. But he also depended upon the indifference of others. Yet again, in the eyes of the public, a great institution had been found wanting.

For print journalism, the hacking controversy was no less a disaster, forcing the closure of the News of the World, the resignation of its former editor, Andy Coulson, as Number Ten’s director of communications, and Lord Leveson’s sweeping inquiry of 2011–12 into the conduct of the press. At the time of writing, the regulatory regime to which British publications will submit themselves is still unresolved. But much more is at stake here than the precise (and varying) rules to which the press will be subject.

In 2003, the disclosure by the New York Times that one of its reporters, Jayson Blair, had falsified or plagiarised content in 673 articles in the course of four years forced the paper to publish a 14,000-word review of his misconduct. This was not just a collapse in editorial control and judgement. The debacle represented a mortal threat – narrowly averted – to one of the great institutions of American civic life. It is surely no accident that President Trump routinely tweets that the New York Times is ‘failing’: he knows which media organisations to target – the ‘halo brands’ – and which will seek to hold him truly accountable. For all the talk of the ‘dead tree press’, it was the Washington Post that forced the President to sack his National Security Adviser, Michael Flynn, after only twenty-four days.

The task of populism is to simplify at all costs, to squeeze inconvenient facts into a preordained shape, or exclude them altogether. The task of journalism is to reveal the complexity, nuance and paradox of public life, as well as to ferret out wrongdoing and, most important of all, to water the roots of democracy with a steady supply of reliable news. Precisely when trust in the media is required most it has, according to global opinion polls, fallen to an all-time low.

We live in an age of institutional fragility. A society’s institutions act as guard rails, the bodies that incarnate its values and continuities. To shine a bright light on their failures, decadence and outright collapse is intrinsically unsettling. But that is not all.

Post-Truth has flourished in this context, as the firewalls and antibodies (to mix metaphors) have weakened. When the putative guarantors of honesty falter, so does truth itself. The philosopher AC Grayling may well be right to identify the financial crisis as the germinal moment that led in a matter of years to the Post-Truth era. ‘The world changed after 2008,’ he told the BBC in January 2017 – and so it did.

If institutional failure has eroded the primacy of truth, so too has the multi-billion-dollar industry of misinformation, false propaganda and phony science that has arisen in recent years. Just as Post-Truth is not just another name for lying, this industry has nothing to do with legitimate lobbying and corporate relations. Businesses, charities, campaigning bodies and public figures are perfectly entitled to seek professional representation in the maze of government and media. This is all part of the rough and tumble of policymaking, consultation and publicity, and no threat to a healthy civic structure.

Quite separate, however, is the systematic spread of falsehood by front organisations acting on behalf of vested interests that wish to suppress accurate information or to prevent others acting upon it.

As the campaigning journalist Ari Rabin-Havt has put it: ‘These lies are part of a coordinated, strategic assault designed to hide the truth, confuse the public, and create controversy where none previously existed.’

This assault has its distant roots in the launch of the Tobacco Industry Research Committee in 1954, a corporate-sponsored body set up in response to growing public anxiety over the connection between smoking and lung disease. What made the committee so significant was the subtlety of its objective. It sought not to win the battle outright, but to dispute the existence of a scientific consensus. It was designed to sabotage public confidence and establish a false equivalence between those scientists who detected a link between tobacco use and lung cancer and those who challenged them. The objective was not academic victory but popular confusion. As long as doubt hovered over the case against tobacco, the lucrative status quo was safe.

This provided climate change deniers with a model for their own campaigns. Marc Morano, the former Republican aide who runs the website ClimateDepot.com, has described gridlock as ‘the greatest friend a global warming skeptic has because that’s all you really want … We’re the negative force. We’re just trying to stop stuff.’

Foreshadowing Gove’s attack on ‘experts’, Morano has conceded that the ideologically driven layman is often at an advantage when taking on a scholar: ‘You go up against a scientist, most of them are going to be in their own policy wonk world or area of expertise … very arcane, very hard to understand, hard to explain, and very boorrring.’

It follows that the trick is to provide disruptive entertainment as a distraction from plodding science. The media, especially twenty-four-hour news channels, are constantly hungry for confrontation, which often creates the illusion of a contest between equally legitimate positions – what Kingsley Amis called ‘pernicious neutrality’.

A rolling dispute of this sort was certainly the objective of those behind ‘Climategate’: the disclosure in 2009 of thousands of emails and files hacked from a server at the University of East Anglia’s Climate Research Unit. The brilliance of those reporting on the cache was to select phrases and sentences that appeared, collectively, to suggest an academic cover-up, and a humiliating gap between what the scientists claimed in public and what they said to one another in private.

As embarrassing as the emails undoubtedly were – revealing moments of exasperation and frustration – they did not, as was routinely claimed, undermine the science of climate change. To take an example: in one message, Dr Kevin Trenberth, an MIT scientist, wrote: ‘We cannot account for the lack of warming at the moment, and it is a travesty that we can’t.’ A clear enough admission, surely? Not so, as it transpired. The ‘travesty’ to which Trenberth was actually referring was the absence of ‘an observing system adequate to track [climate change]’. He was not in any sense retracting his scientific conclusions about global warming but regretting a shortfall in the infrastructure that he and his colleagues needed.

Report after report – by Penn State University, a UK parliamentary committee, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Inspector General’s Office, fact-checking sites and an independent inquiry commissioned by UEA itself – found that the files did not undermine the scientific consensus on climate change, or impugn the academic integrity of the scientists involved.

But the deniers’ work was already done. According to a survey by Yale University, public support for global warming science fell from 71 to 57% between 2008 and 2010. A more recent UK poll, published in January 2017, suggested that 64% of British adults believe that the climate is changing, ‘primarily due to human activity’. This might seem like a reasonable majority. But consider the stakes: eleven years after the UK government’s publication of the official Stern Review on the Economics of Climate Change, and nine since the Climate Change Act put emission reduction targets into law, the public is still not overwhelmingly persuaded that the very survival of humanity is at risk.

Before his election, Trump claimed that the ‘concept of global warming was created by and for the Chinese in order to make US manufacturing non-competitive’. Since taking office, he has surrounded himself with climate-change sceptics. The principal objective of the deniers – to maintain the status quo – has never faced better odds.

Their insight, shared by the opponents of healthcare reform in the US, is that evidence-based public policy can be undermined by the alignment of well-crafted propaganda and ideological predisposition.

These campaigns of disinformation have paved the way for the Post-Truth era. Their purpose is invariably to sow doubt rather than to triumph outright in the court of public opinion (usually an impractical objective). As the institutions that traditionally act as social arbiters – referees on the pitch, as it were – have been progressively discredited, so well-funded pressure groups have encouraged the public to question the existence of conclusively reliable truth. Accordingly, the normal practice of adversarial debate is morphing into an unhealthy relativism, in which the epistemological chase is not only better than the catch – but all that matters. The point is simply to keep the argument going, to ensure that it never reaches a conclusion.

• Matthew D’Ancona is a journalist and author. His latest book Post Truth: The New War on Truth and How to Fight Back out now