The UK does not want Brexit, says Professor Adrian Low as he analyses the polls since the EU referendum

In total 46.5 million had the right to vote in the Brexit referendum.

Of those 33.5 million – or 72% – voted.

Compared to general elections it was an exceptional turnout, yet still, 12.9 million people did not vote.

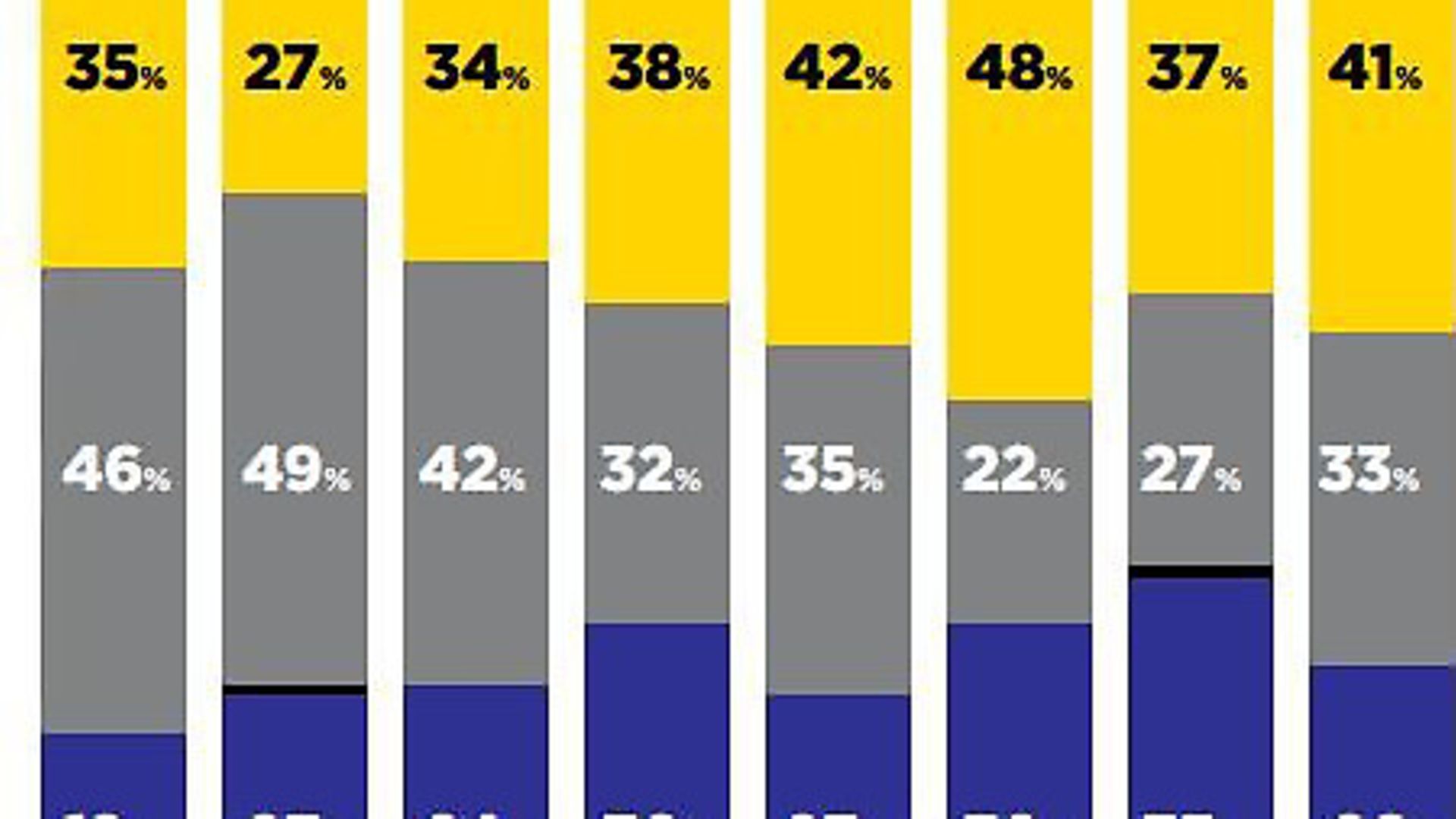

Since the referendum there have been 13 polls, 11 of which show preferences of both voters and non-voters. Among the non-voters there is a continuing average of about 13.8% majority for Remain. Click here to view poll data.

What this means is clear – the UK electorate as a whole does not want Brexit.

The maths is relatively simple. If, as the polls predict, nearly 14% more abstainers want Remain rather than Leave that amounts to 14% of 12.9 million, which is nearly 1.8 million. That is greater than the 1.3 million Leave majority at the referendum.

For about three weeks after June 23 referendum there was a big reversal of the vote in the polls. All of the numbers indicated the UK did not expect the Leave majority of 3.8%.

Leavers changed their minds and the polls reversed that majority in favour of Remain. It was a major reversal into more than double percentage figures. Latterly the significant factor in the polls, for Remain, is the preferences of the non-voter.

Some say, non-voters have forfeited their right to have their views considered. Others that the losers in the referendum since they have lost, should accept the position.

However if the country, both then and now, actually does not want Brexit, what is going on?

The non-voters are 13.8% biased towards staying in the EU. Two possible scenarios, amongst many, are complacency of a Remain victory and the organisational skills of our young people.

The pre-referendum polls said Remain would win. A Remain supporter that needed to leave work early to vote, for example, may not have bothered to rush because Remain is going to win anyway – the polls said so. If you were a Leave voter, you know your vote may actually be needed. So the early journey home is worth it. Such behaviour is well documented in political research. It is why some countries ban polls in the final week of a campaign.

Secondly most 18-24s did not vote but those who did were 75% for Remain. Approximately 1.5 million University students register to vote in their university town but June 23rd would have been, for most, after term had ended. How many of them would have realised early enough to plan a postal vote into their lives? Recognising and planning postal votes might not have been at the top of their agenda.

As of October, about 10% of both Leave and Remain voters have either swapped their preference (5%) or now respond that they do not know what to think (the other 5%). These balance each other, so it is the non-voters who create the electoral majority in the polls for Remain.

Should there ever be another referendum, no-shows last time might be no-shows again, but at least in any second vote the Remainers know they would be on a back foot.

And demographics also change the scene. There are 750,000 new 18 year old voters each year and a balancing number of deaths, the vast majority in the 65+ range. The 18-24s voted 75% in favour of Remain, the 65+ group voted 35% for Remain. The 40% difference means that year-on-year, assuming the referendum voters stick with their choice, there will be 300,000 added to the Remain camp. The calculation is complex because the different groups had different turnouts but a Financial Times model has the Remain camp winning a referendum vote (ignoring all the non-voters) by the end of 2021.

Actually, the tipping point is likely to be sooner than that.

On October 7 the government announced it would implement a manifesto promise to give UK expats who had been outside of the UK for 15 years or more, the opportunity to vote. From a Remain point of view it might have been wise to do that before the referendum. More recent UK expats already had the vote. Estimates vary between one million and five million long-term-resident expats. It is likely that the overwhelming majority of these, like the more recent expat community, would vote Remain.

Two other groups were excluded from voting, both groups requesting voting rights but were denied them. According to the National Union of Students 75% of 16-18s wanted a vote. They had a vote in the Scottish Independence Referendum and this one was just as important. If they voted as the 18-24s, 1.5 million of them would have been 75% for Remain.

And EU residents of the UK, or to be accurate, non-UK, non-Eire EU residents of the UK. In total 2.25 million EU residents in the UK were not allowed to vote. These are probably the group whose lives are most likely to be dramatically affected by Brexit. Their argument is that good democracy is about those who are likely to be affected most having a vote. Needless to say they would most likely have voted to Remain.

So, even if we consider the whole UK population there are two big groups that add substantial numbers to the Remain majority from the electorate. The UK does not want Brexit.

Ultimately it is up to government to decide whether the will of the UK people and/or the will of the UK electorate (voting and non-voting) has any value after a referendum. If it does have value then, at some point in the future the people should have the opportunity to demonstrate what seems to be their wish to Remain. If all UK residents and expats are included, the polls suggest the vote would be much more conclusive than the previous one.

Revd Adrian Low is emeritus professor of computing education at Staffordshire University, and Church of England chaplain to the west of the Costa del Sol in Spain.