No one benefits from the absurd idea that Britain is being punished by a dictated settlement – like the Germans after the First World War – says Stephan richter, the Berlin-based Editor-in-Chief of The Globalist

In an article for the Guardian this summer, the historian Timothy Garton Ash issued a stern warning that a ‘humiliating Brexit deal risks a descent into Weimar Britain’.

He sees a danger that ‘a milder, peacetime, bureaucratic version of the punitive Versailles treaty imposed on Germany’ may be in the offing for the UK.

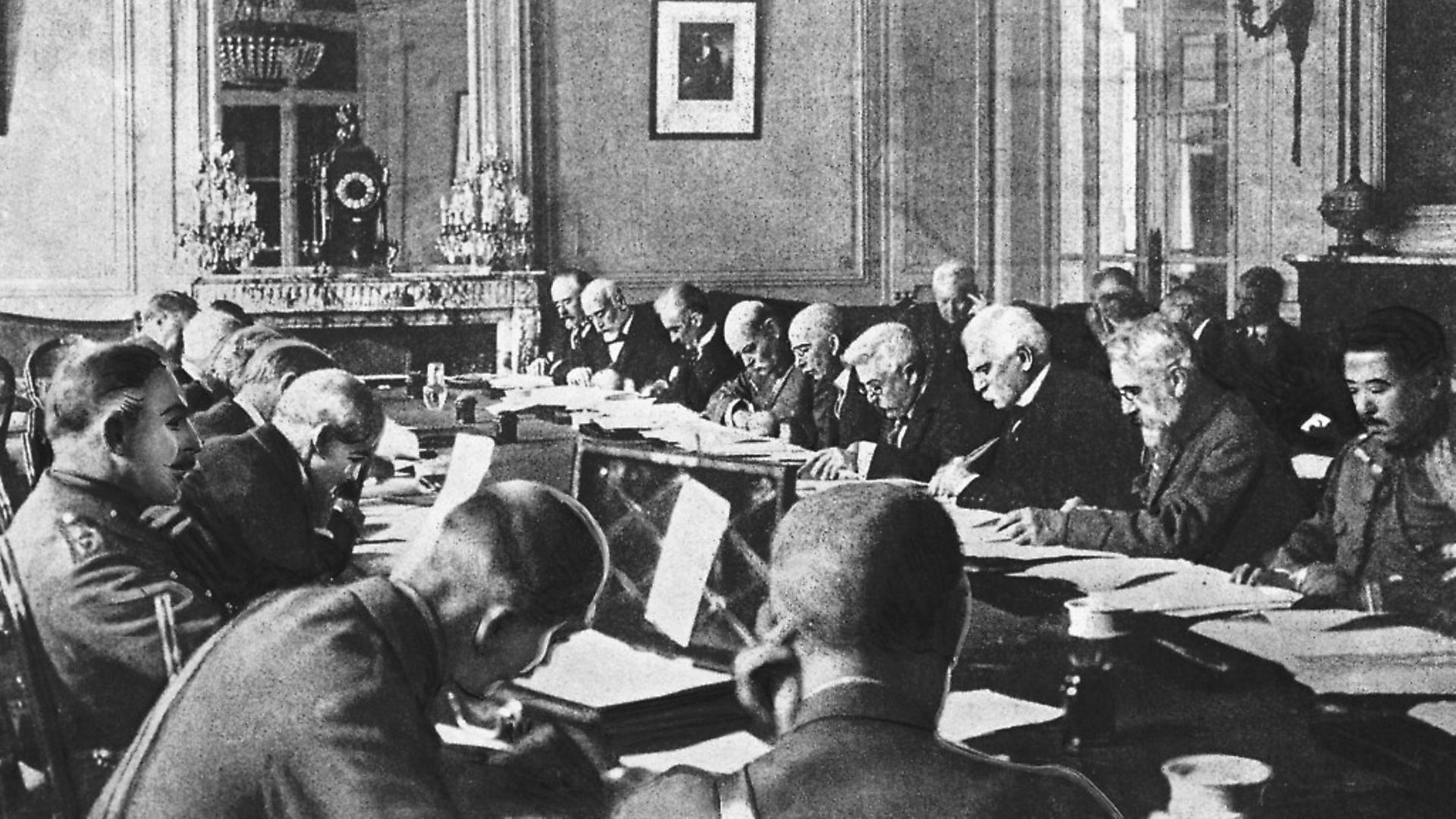

With that, as in 1919, the politically very charged question of a ‘dictated peace’ (‘Diktatfrieden’) is once again with us a full century onward.

As a matter of fact, the Versailles-style humiliation argument has been in the air for well over a year. It was ripe for the making ever since many Tory politicians as well as BBC interviewers regularly started charging their EU interlocutors with being keen on ‘punishing’ Britain for Brexit (by not offering the country the ‘bespoke’ deal Theresa May wants).

Even so, the mere predictability of the Versailles argument does not mean it should be dismissed out of hand. After all, Europe spent much of the 20th century untangling itself from the ill spirits of the extremely one-sided 1919 Versailles Treaty.

The treaty assigned virtually all of the blame, and corresponding punishment, for the First World War to the Germans. That outcome may have been politically convenient at the time, but it was arguably false historically and inarguably disastrous economically.

In his very prescient treatise The Economic Consequences of Peace (1919), John Maynard Keynes, the eminent British economist, pointed out the key deficiency of the Versailles Treaty: it accomplished the opposite of what Europe really needed at the time – an equitable and integrated economic system. Then, as now, this is the goal Europe must strive for.

The enormous difference between then and now is that Europe essentially operates on the basis of such a ‘treaty’ – i.e., the EU and all its rules and regulations. The UK, on its own volition and as a matter of its understanding of national sovereignty, is free to exit from this arrangement. Understandably, that must occur on the basis of the rules established by the club.

The fundamental error on the UK side is to assume that the (Br)exit manoeuvre is a negotiation between two equals. It is not. It is a settling of the accounts between the club’s management and the departing member.

The current UK effort goes far beyond that. It is akin to a club member wanting to leave the club while preserving most of the benefits of club membership, but without paying the customary club dues in the future (which had been reduced for the UK anyway).

And if that’s not breathtaking enough, it appears as if the UK – although no longer a member – also wants to be at least on the executive committee of the club, and preferably one with veto powers. Ludicrous? You betcha. And yet, this is an apt description of the UK negotiating position.

The audacity, if not pompousness, of that manoeuvre leaves the rest of Europe speechless. Nobody can comprehend why it is British politicians, of all imaginable political cultures, that feign ignorance about having to follow club rules and instead claim ‘punishment’ for not getting their version of ‘Europe à la carte’. To any outsider at least, this betrays the core of British (club) culture.

It should be obvious for many reasons why the UK offer – continuing the past practice of having one set of rules for all other, lesser EU members and then another, much more flexible set that is solely available to the UK – is a non-starter.

Moreover, giving in to the presumably small British demands on labour mobility, while maintaining full access to the single market for goods, runs counter to the prescriptions that Keynes would have for this day.

He would surely counsel against unravelling Europe’s economic integration fabric just to satisfy the demands of one nation that wants to stand further apart from the rest.

The other reason for firmness ought to be especially evident to the UK side: Just as the country’s social traditions are steeped deeply in clubs (and their rules), so do UK legal traditions provide the country with intimate knowledge of the power of precedent.

And the precedent that making this ‘little compromise’ on labour mobility would create is terrible. Every single one of the remaining 27 EU members would threaten exiting from the EU if they didn’t get their own little compromise. Soon enough, the whole EU edifice would collapse.

Under those circumstances, insisting that rules be followed, as Michel Barnier does, is neither an act of stubbornness nor a matter of vindictiveness. It is a matter of European statecraft.

It is telling that the Germans, the Dutch and the Poles – the UK’s traditional allies inside the EU – have not fallen for any of the luring UK ‘bespoke deal’ music.

In fact, they haven’t moved by as much as an inch. They understand that the choice between satisfying the whims of the UK and preserving the integrity of the EU isn’t even a choice. The outcome is preordained.

The reality is even worse for the UK side. The Dutch prime minister Mark Rutte swiftly seized the opportunity to take over the mantle as the EU’s most pragmatic, trading-oriented nation from the UK. He has even managed to get another seven EU members to support his stance.

And the Polish government, despite the PiS Party’s profound dislike of Germany, has quickly detected the potentially enormous economic fallout from Donald Trump’s unilateralism in trade. The country’s thriving economy depends on full access to EU markets, and Germany in particular.

Under those circumstances, threats like resorting ‘to the traditional British policy of trying to divide and rule on the continent’, as Garton Ash weaves into his argument, fall completely flat.

In a way, the UK acts a bit like the Southern states did in the United States in the run-up to 1865. Both the UK now and the American South back then want to preserve all the benefits of staying in the Union, while being allowed to secede in order to preserve its supposed inalterable traditions (feudalism and slavery in the South’s case, unfettered sovereignty in the UK’s).

Unlike the US case, the EU has a ‘secession’ clause. The UK does not need to go to war over its desire to part company. But paying up for the costs of divorce it must. That is not punishment. It’s just the club’s rules.

The ‘pragmatic realism’ that Garton Ash rightfully demands would have the UK evaluate the benefits and costs of its EU membership versus standing alone.

Even if there were no other reason than the profound lack of the required administrative capacity on the part of the UK to pull off a Brexit with all that this implies, the UK’s choice ought to be clear.

But for a nation that has a long tradition of always acting smartly in the pursuit of its economic self-interest, the choice is even clearer. EU membership benefits the UK and its people greatly.

Not least because being an integral part of the European division of labour, UK manufacturing has received a powerful boost. This, too, would vanish with Brexit.

Stephan Richter is editor-in-chief of The Globalist. Follow him @stephan_richter