The sun has just risen, but the Colombian side of the Simon Bolivar International Bridge is already a mass of life. Families stand dazed with their luggage, as assorted hustlers and hawkers shout and prowl.

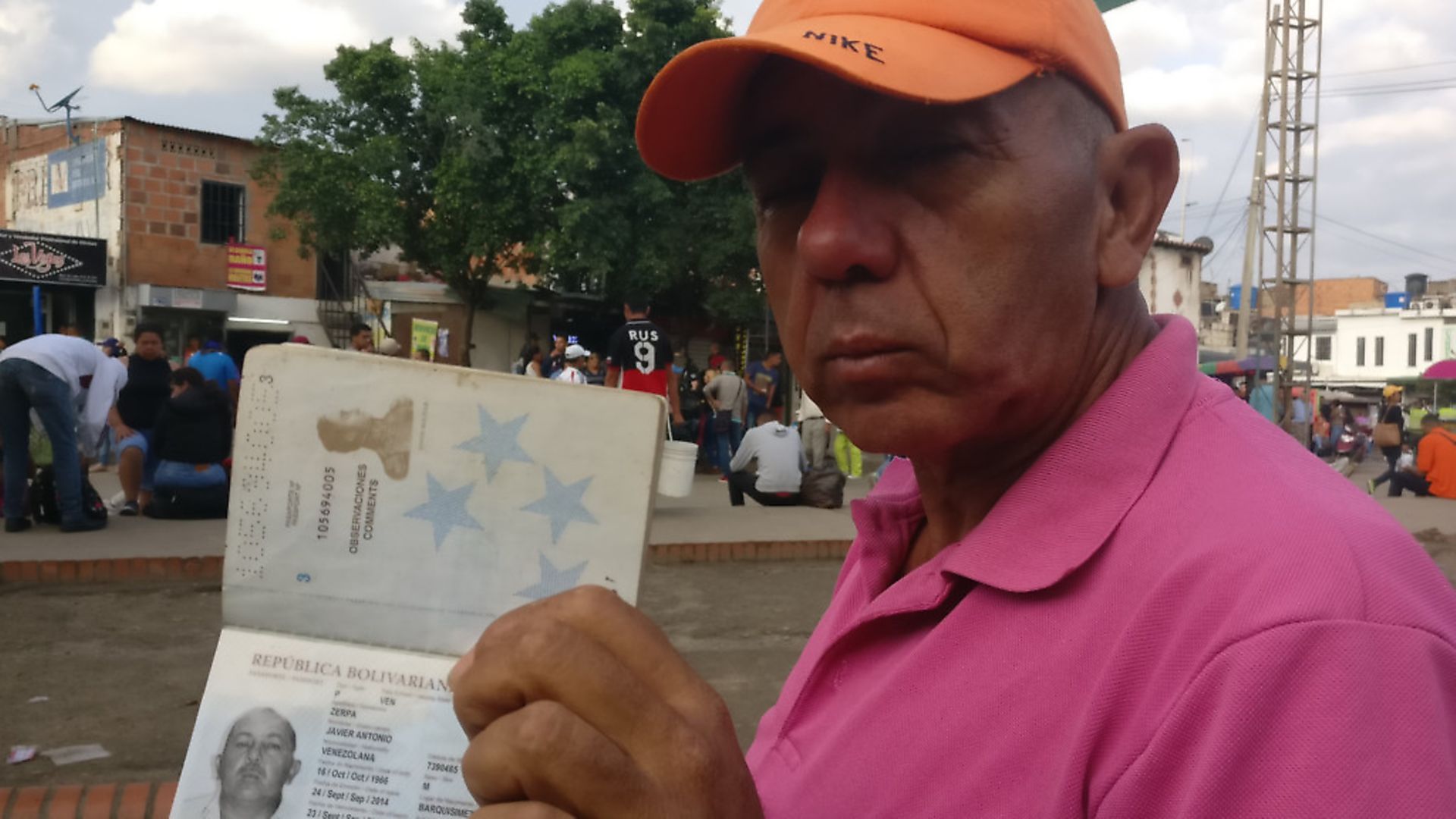

But among the swirling crowds, one man sits alone. Javier Zerpa crouches on a kerb, thumbing through old photographs, scraps of paper scrawled with the telephone numbers of distant contacts, and a Venezuelan passport.

He is well-dressed, for a man who just spent his first night sleeping rough, in a pink polo shirt, jeans and suede shoes. But his smart appearance belies the severe anxieties of a once-proud man whose every certainty has been tossed to the winds.

‘I’m crushed,’ the 49-year-old says through tears. A former second-in-command of his city’s police motorcycle force, Zerpa has now joined the hundreds of thousands of other Venezuelans leaving their homeland. Like the former policeman, they are fleeing a country where a crumbling economy has made their money virtually worthless and caused shortages of food, medicine and other basic goods. Consequently, the migration crisis in neighbouring Colombia has gathered pace.

Experts warn it is comparable in scale to the higher-profile Rohingya and Syrian crises, and is threatening to destabilise the entire region. No one knows the precise number of people who have left Venezuela – once the most prosperous country in Latin America – though it is estimated to be up to four million since 2014.

Colombia has officially received more than 500,000 Venezuelan migrants since the second half of 2017. But many believe the true number could be around a million. For numerical contrast, last year’s influx of Rohingya refugees to Bangladesh was around 671,000.

‘It’s a hard life in Venezuela, the economy is trashed,’ says Zerpa, who is from the northwestern city of Barquisimeto.

‘The minimum daily salary is 25,000 bolivars per day (a black market rate of around 11 US cents, according to frequently referenced website DolarToday). But to buy flour to make arepas (a staple food in the region), it’s 150,000 bolivars (65 cents). Thirty eggs is 300,000 bolivars ($1.30) – that’s 12 day’s work so my family of six can eat for a few days. A kilo of meat is 400,000 bolivars ($1.73).’

He adds: ‘Children are dying of malnutrition in the hospitals, but our president doesn’t want to admit this.’

Hunger has been a defining characteristic of the ongoing crisis in Venezuela. So far, socialist President Nicholas Maduro has refused to allow international aid into the country.

The majority of Venezuelan migrants I spoke to in Cucuta cited a lack of food as their main reasons for leaving, though some mentioned the scarcity of medicines. Zerpa needs pills for hypertension but hasn’t taken them in four months. But not being able to eat was the final straw.

‘I have no money, I can’t eat,’ he says. ‘We had one meal per day. Often, I didn’t eat so I could give the food to my sons.’

Then, he pulls out his passport, flicks to the identity page, and reveals a photo of a very different man. The full faced, 90kg police officer in the ID photo is a stark contrast to the gaunt, 70kg migrant who now lingers at the border.

But, with a passport, Zerpa is one of the lucky ones. He can use it to gain Special Permanent Permission (PEP), enabling him to work and access services in Colombia. He can send money he earns back to his family, who remain in Venezuela.

‘My cousin is in Medellin and works in a milk factory,’ Zerpa says. ‘I hope I can find a job there.’

The border between Colombia and Venezuela runs for 2,200km, and controlling it is fraught with challenges. It has traditionally been very porous, and in better days, many Colombians used to have jobs in towns just across the border in Venezuela. People have always crossed it to buy goods – even to see family members – though most visits now flow towards Colombia. Some Venezuelans cross just for the day to buy food, medicines or to work illegally.

But much of the border – even areas very close to Cucuta’s main crossing – is extremely lawless. It should be considered ‘in an active conflict context’, according to Carolina Munin, of Cucuta’s office of the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR). The restive Norte de Santander department, of which Cucuta is capital, is home to a number of organised armed groups, including the guerrillas of the National Liberation Army (ELN).

‘Venezuelan migrants are 100% immersed in dynamics of conflict,’ Munin says. This greatly exacerbates the situation, putting migrants at risk of forced recruitment and sexual exploitation.

It has also contributed to a burgeoning – and highly dangerous – human trafficking trade. While there are six legal points to cross from Venezuela into Colombia, there are 280 known trochas, or illegal pathways, through which to enter the country. The state does not control these areas.

Instead, bandits and gunmen stalk the trails, charging people to cross into Colombia. Migrants – including women and children – are exposed to extreme risk, and sometimes what few possessions they carry are stolen. Murders are said to take place every day on the trochas, and mass killings are frequently reported in the local press too. But those taking the journey see it as their only chance of a better life.

Colombia’s president Juan Manuel Santos announced in February that border controls would be tightened, and 3,000 troops would be deployed to increase security. But critics have said this would just push migrants to take the dangerous illegal routes.

‘As long as you can pay something, you can pass through,’ says Father Francesco Bortigenon, an Italian priest who runs services helping migrants in Cucuta.

‘No way you can stop people passing through there,’ he says. ‘The situation is getting heavier and heavier. How can they go back? They have no money, no food, no healthcare. They are in danger for no reason.’

Those migrants in Colombia without proper documentation face a tough and uncertain future, with no access to non-emergency health care, education or social services. Many families sleep rough, others join rapidly growing communities across the country. Most are forced into informal work or begging. Many are hungry, just as they were in Venezuela. Xenophobia is also rife, magnified by the slant of some local media coverage, relief workers say.

Confusion abounds over the status of various migrants – only a small number are applying for asylum. But earlier this month, the UNHCR advised that Venezuelans who fled to Colombia should be given similar protections to refugees.

Colombia – which has endured decades of civil war – is a country more used to producing desperate migrants than receiving them. It has 7.2 million internally displaced people, one of the highest rates in the world. Among the recent influx from Venezuela are at least 190,000 Colombians who previously left for safety or work in the neighbouring country. It has been a difficult issue for the authorities to grasp. Santos himself said: ‘Colombia has never lived through a situation like what we have today.’

And it is likely to get worse. A recent Gallup poll showed 41% of Venezuelans – around 12 million people – want to emigrate, with Colombia the preferred destination for many.

There are signs the international community is waking up to the emergency. Last week, the US announced $2.5m (£1.7m) will be given to help provide emergency food and medicine, its first donation to the crisis. Americans have also been banned from transactions involving the ‘Petro’, a cryptocurrency introduced by the Maduro government. And the International Monetary Fund (IMF) is set to consider a formal request from the Colombian government for assistance, following a meeting at a G20 summit earlier last week.

But not all the Venezuelans who cross into Colombia will stay there. Already this year, 140,000 migrants have passed through the country. And as soon as they cross the Bolivar bridge, they are greeted by waves of touts selling bus tickets, crying ‘Chile! Ecuador! Peru!’

In a large building to the side of the road, Anyeli Flores waits with two friends for her ride to Ecuador. She left her three children with her mother in Maracay, in Venezuela’s north, having been unable to supply them with nappies and milk.

‘I decided to divorce my husband because he didn’t want to leave,’ Flores says. ‘He doesn’t have much expectation of life outside the country, but I am thinking of my children.’ Flores, like many others, speaks of the rising, unpredictable prices in her home country. She saw the desperate measures it forced people into: many of her friends sold their hair to murky businesspeople who are running a cross-border trade fuelled by the salon industry in Colombia. ‘I didn’t want to – I love my hair and its hard for me,’ she says, clutching her jet-black locks. ‘It’s so sad to see people do that.’

Like all the migrants I spoke to, Flores said she would not return until president Maduro is out.

But Zerpa, the policeman, perhaps puts it most eloquently. ‘For Venezuela to have a future, the president must leave and be replaced by someone with a conscience,’ he says.

‘Venezuela is a rich country, with minerals, oil, diamonds, coal,’ he continues. ‘I don’t know how this will end, but I hope it will end well. Now, there is no future for the children in Venezuela. If you can help my country, please do it.’

Will Worley is a freelance journalist interested in foreign affairs. He can be found on Twitter @willrworley