Nick Hopkinson recounts the long campaign by the separatist movement in his native Québec and finds striking parallels with the UK’s departure from the EU.

There are many similarities between our Brexit psycho-drama and the Parti Québécois’ attempts to leave Canada in the 1980s and 1990s. The Québec experience can provide some insights into how the Brexit process may unfold in the United Kingdom, and perhaps even some hope for those of us who wish to rejoin the European Union.

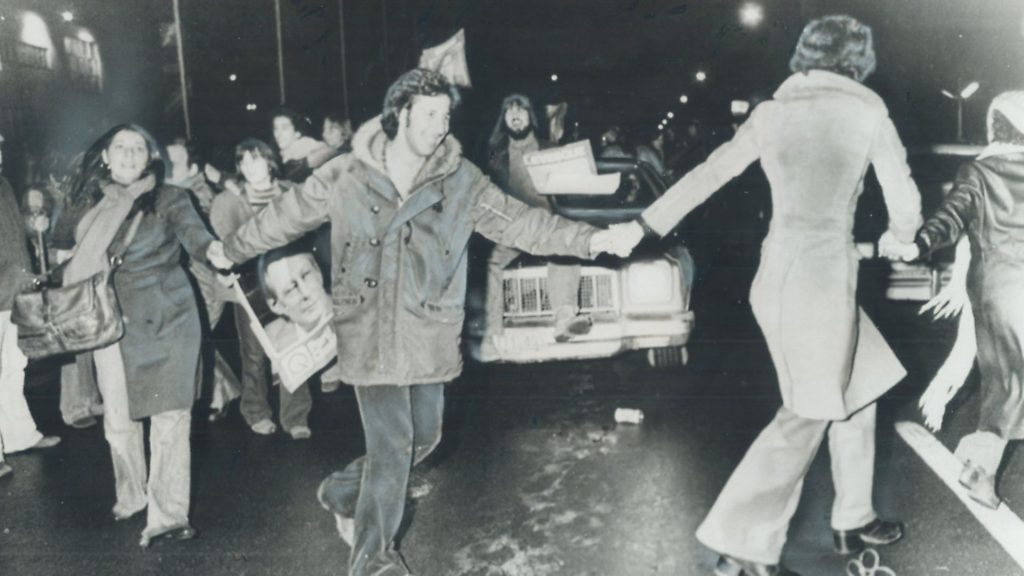

As an “Anglophone” who grew up in Montreal against a background of nationalism and referendums, Brexit is largely a déjà vu nightmare. There are, of course, significant differences. The campaign for Brexit has succeeded, while that for Québec separatism has receded. Another is the level of violence involved. From 1963 to 1970, Québec’s mini version of the Troubles culminated in the British trade commissioner, James Cross, and the provincial vice premier, Pierre Laporte, being kidnapped. Cross was eventually released, but Laporte was murdered. During that time, I recall bombs blowing out windows of my school and it then being guarded by the Canadian army.

As I grew in political awareness, I eventually came to regard the then European Community as an effective way for different nations and peoples to coexist prosperously in peace. With little future for Anglophones in Québec, my journey took me from Montreal to working eventually for the British government, which was at the time the champion of EU enlargement.

Québec and Brexit experiences have given me a deep dislike of nationalist populist elites who offer false hope to the less content and ‘left behind’, who will be less well-off as a result of what they advocate. Such leaders offer hope but their politics divide. They raise and magnify often dormant tensions, and create new ones that did not exist before. Their populist nationalism discriminates against minorities, erodes individual rights and undermines democracy.

Both Québec separatists and Brexiters exaggerated the threat to national identity, culture and language to validate their political ambitions. Québec nationalism was in part stoked by fears that Francophone identity and language were being swamped by English dominance of North American culture and the media.

Advocates played up the threat from non-English immigrants (Allophones) gravitating towards the Anglophone community. Some even argued the only genuine Québécois were Francophones. Slogans surfaced such as “le Québec aux Québécois”. “Maîtres chez nous” (masters in our own home) – messages that are not too dissimilar from “take back control”. Non-Francophone youth, even if bilingual and born in Québec, experienced their own “hostile environment”.

Both Québec separatism and Brexit also portrayed themselves as anti-establishment movements. The elite were portrayed as Anglophones, often living in the affluent Montreal suburb of Westmount, conveniently forgetting many Anglophones were working class people living in Point St Charles or middle class, living in Montreal’s West Island. The UK’s so-called “Remain elite” was similarly drawn from all classes.

Separatists conveniently forgot their populist leaders were an alternative elite in waiting, a number of whom were privately-educated and grew up in affluent Outremont. Similarly, Brexit elite leaders are not strangers to Eton and Dulwich College.

Another parallel is the way nationalist politicians blamed their own failings on others – whether the EU or the Canadian federal government – and pretend “independence” is the solution.

In 1964, prime minister-to-be (and father of the current Canadian PM) Pierre Trudeau and six others wrote in their Canadian Manifesto: “To use nationalism as a yardstick for deciding policies and priorities is both sterile and retrograde. Overflowing nationalism distorts one’s vision of reality, prevents one from seeing problems in their true perspective, falsifies solutions and constitutes a classic diversionary tactic for politicians caught by facts… separatism in Québec appears to us not only a waste of time but a step backwards… to take (Canada) apart would require an enormous expenditure of energy and gain no proven advantage.”

Both separatists and Brexiters made the fundamental mistake, whether deliberately or not, of promoting the idea that cutting external links increases “effective” sovereignty. Separatists essentially argued they would be more sovereign without seats in Canadian institutions, whether in the Ottawa parliament or Bank of Canada. Many separatists believed an independent Québec could have its cake and eat it too.

Robert Bourassa, Québec premier during separate spells in the 1970s and 1980s, observed “there are maybe 60% who support “sovereignty association” (a softer form of independence giving Québec the exclusive power to determine its own laws, levy its taxes and establish relations abroad), but three quarters of them want to continue sending politicians to Ottawa”.

Yvon Deschamps, the Québécois comedian, observed “what Québecers want is an independent Québec within a strong and united Canada”. Our own Brexit comedians have also at times seemed to think an “independent” UK can have all the benefits of EU membership.

If Québec had separated from Canada, it risked losing access to a North American market 40 times larger than its own, which it enjoyed under the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). Brexiters are not only jettisoning an EU market eight times larger than ours, but also a deeper trade arrangement and EU trade agreements with another 60 countries, including Japan and Canada.

Gordon Ritchie, a senior Canadian diplomat, noted that if the US had to negotiate with an independent Québec, it would raise Québec’s high level of state intervention in key sectors, factors which were less prominent in the NAFTA negotiations. Bill Merkin, a senior US official, stated “if there were a messy situation in Canada… that would make it very difficult for the US to enter into any kind of relationship with Québec. The US is going to be concerned about maintaining good relations with Canada”. Similarly, our international trading partners (even the US) will prioritise trade agreements with the (larger) EU before they conclude anything meaningful with us.

The first referendum on whether Québec should pursue a path towards sovereignty was held in 1980. It saw 60% of Québecers vote against the move. Following this, Anglophone and Allophone populations were steadily reduced by legislation curbing access to English speaking schools and the outlawing of English as an official working language in “Bill 101”. The number of students in English schools in 1976 more than halved from 236,000 to under 100,000 in 1990. By the time of a second referendum, in 1995, many non-Francophones had left, so there was a smaller support base for staying in Canada: 9% more voted for a harder version of independence, although 51% overall voted to stay in Canada. The situation is not quite analogous, but it is worth noting that in the 2016 EU referendum, most of the three million EU27 citizens were barred from voting (in line with general election rules), even though they pay taxes and would be most affected by Brexit.

Separation takes longer than promised as the power of the larger entity becomes apparent: In last month’s election, the Conservatives pedalled the new myth that a vote for them would “Get Brexit Done”. It won’t. In the course of Canada’s constitutional crisis in the 1990s, prime minister Jean Chrétien acknowledged “it would be irresponsible to believe that an agreement between an independent Québec and the rest of Canada could be concluded easily and quickly. It would take years to achieve and resolve”.

The larger negotiating partner holds almost all the cards and the demandeur, the smaller separating entity, doesn’t. Professor Leon Dion argued: “English Canada will not make concessions.” We similarly cannot expect any generosity from the EU27.

Another parallel is the way that separation threatens national unity. Pierre Trudeau said “if Canada is divisible, Quebec should be divisible too”. The northern two thirds of Québec was granted by the federal government to the province of Québec as an administrative convenience in the Québec Boundary Extension Acts of 1898 and 1912. This effectively tripled the size of Québec beyond the original French colony straddling the St Lawrence river.

The First Nations, the main inhabitants of northern Québec, firmly resisted joining any independent Québec. In 1991, Ovide Mercredi, then leader of the Assembly of First Nations, stated “if Québec separates… the aboriginal people will stay with Canada. They should not be forced to be part of a new state that they have not consented to”.

Anglophones who formed a majority in Montreal’s West Island also sought to remain part of Canada. With a hard Brexit certain, pressures are growing for an Irish border poll on unification and a second referendum on Scottish independence.

Separation also means businesses leaving and GDP declining. If politicians pursue policies which harm business, they downscale, and sometimes relocate. Economic growth falls as a result. Although its economy has grown, Québec since 1976 has been one of Canada’s slowest growing provinces. While the uncertainty of separation is not the only reason, it is an important factor relegating Montreal from Canada’s to Québec’s business capital.

The day the separatist Parti Québécois came to power in November 1976, Sun Life, the major insurer, which occupied the one-time largest commercial building in the British Empire, announced it was moving its headquarters and most of its staff to Toronto.

Pharmaceutical company Ingersoll Rand invested $30 million in a new facility in Ontario instead of Québec, citing “the use of English (as being) very important to be competitive”. Foreign investors became less interested in a Québec that no longer allowed firms to operate in North America’s lingua franca. Analogously, leaving the (single) EU market will lose investment and jobs in the UK.

As opportunities and growth decline, and rights are weakened, people leave. Justice Jules Dechênes noted Bill 101 “demonstrates a totalitarian concept of society … which put the collectivity above the rights of the individual”.

An estimated one million Anglophones and Allophones have left Québec since 1976, many highly educated. This large population movement was barely noticed internationally as Québecers were easily absorbed elsewhere, largely in the growing Ontario economy. There were no images of mass hardship, but for many the personal hurt of relocating endures.

Meanwhile in the UK, net inflow of EU27 citizens is falling rapidly even though the need for immigration in our ageing country grows (not least filling 100,000 healthcare professional vacancies).

Those who advocate and support populist nationalism spare little thought for the human consequences of their politics for others. With little future in Québec, I left. Today, thanks in part to the impact of Brexit, my children are thinking of leaving the UK.

Although still on balance good places to live as seen within a global context, Québec and the UK have become less desirable. Some may believe separatism and Brexit can restore national identity and pride, but the reality is that populist nationalist movements consistently fail to fulfil their promises and render their countries less dynamic and globally attractive and admired.

Although the 1995 referendum was lost by the narrowest of margins, it was the second successive rejection of independence. Québec premier Jacques Parizeau resigned and his successor, Lucien Bouchard, promised a third referendum if the Parti Québécois won the next provincial election. Bouchard won the election but never pressed ahead with the referendum, arguably out of fear he might not win it.

Three key developments may have contributed. The federal government recognised any new constitutional negotiations would fan the flames of separatism so it unilaterally recognised Québec as a “distinct society”, thus taking much of the wind out of separatist sails. Secondly, the growing immigrant population in Québec was less interested in a risky separation. Lastly, both the Québec government and people recognised the economy should take priority. The separatist movement ever since has been split over tactics and strategy.

Fortunately, then, Québec has yet to leave Canada, and there is still some hope that Britain can build a close relationship with the EU. For the first time in 50 years, leaving Canada was not a major issue in the 2018 Québec provincial election. Since the 1995 referendum, a younger generation of Québecers, more confident in their place within Canada and more concerned with jobs and improving public services, opted for pragmatism over ideology.

A 2018 IPSOS poll found only 19% in Québec’s 18-25 age range described themselves as “separatists”. A declining minority of older nationalists still of course cling to the past. But most in today’s Québec, like British youth, want to be part of the world, rather than sideline themselves from it.

Like Québecers, there is every chance that a majority in the UK will also eventually reverse this national populist madness.

– Nick Hopkinson is a former director of Wilton Park, the Foreign and Commonwealth Office policy forum, and has written a book on parliamentary democracy and several policy briefs. He posts regularly on Twitter @nickhopkinsonEU.