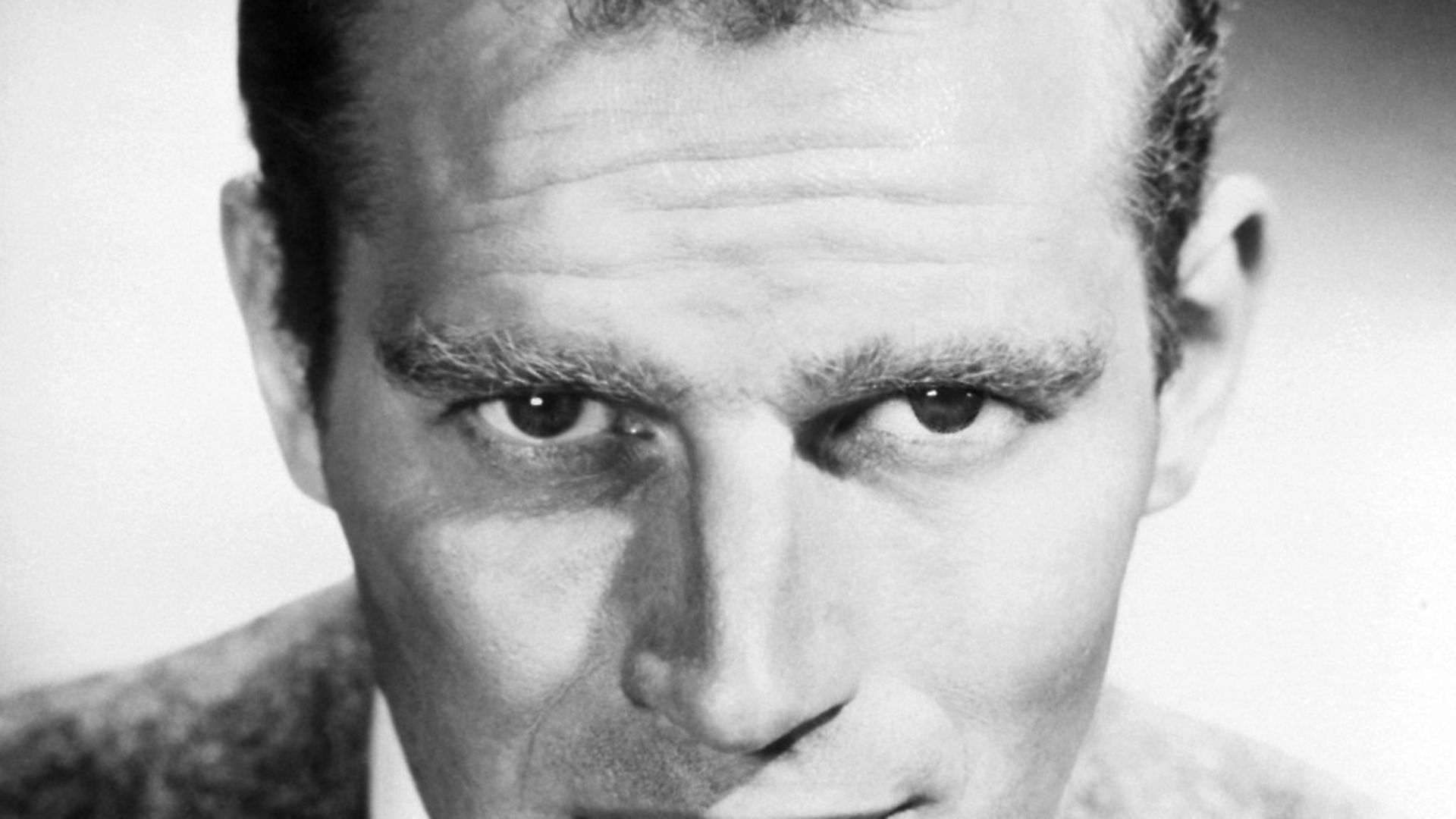

TIM WALKER reflects on an interview with American actor and political activist Charlton Heston.

Charlton Heston was appearing on the London stage in The Caine Mutiny Court-Martial. He was a big guy in a wig whose views on everything from gun control to gay rights had made him politically incorrect before the term had even been invented. The part he was playing in Herman Wouk’s naval drama was a captain who broke down under extreme pressure, and, somewhat optimistically, his publicists suggested that I should use that as the peg to talk to him about what they called his ‘sensitive side’.

This was the mid-1980s when Heston wasn’t remotely fashionable, but, for all that, there was still something about the 62-year-old star of epics like Ben-Hur and The Ten Commandments – in which he’d played Moses – that made him hard to ignore. When I’d gone to see him in the play, the audience had spontaneously applauded when he’d made his first appearance, which may have had a lot to do with his physical stature or the average age of the punters.

He was residing at the Dorchester and there was a queue of journalists waiting outside his capacious suite. When I was finally ushered into his presence, it was clear that finding his ‘sensitive side’ was going to be challenging. He was in a foul temper as the reviews for his performance had been almost uniformly dire. His wife Lydia was also undergoing a back operation in the capital and he had just been on the phone to the hospital as I walked in and it was still in progress.

‘It’s the mean-spiritedness of your critics that gets to me,’ Heston began, before I’d even asked a question. ‘They are all liberals and if the sons-of-bitches were honest, they’d admit it’s my politics they were sitting in judgment upon, not my acting. It’s been a life-long ambition of mine to appear on the London stage and I didn’t expect any favours, but blind hatred is well out of order.’

Still, in terms of the bigger picture, Heston couldn’t complain. His old friend Ronald Reagan had assumed the presidency, and, so far as he was concerned, his country was starting to stand every bit as tall as he was. He approved mightily, too, of Margaret Thatcher as our prime minister. ‘I’m sick of the scroungers, sick of the people who want a free ride,’ he said.

I noticed as he was talking a spare wig on a table in an adjoining room, and, if I am honest, I didn’t take him as seriously as I should. I suppose I saw him as a shouty man from another time, but I see now that the future belonged in a very real way to men like him.

Heston got something I had still to come to terms with, which is to say that politics and showbusiness had started to become inextricably linked and the right had learnt to become a lot more entertaining than the left.

‘America has been afraid of its own shadow for too long and pandered to every crackpot special interest group in its midst, but now, thanks to Ronnie, it’s standing up for itself again and looking after its own best interests,’ Heston told me. ‘I’m proud that a member of my profession is now leading the free world. There’s no more important part of the job so far as I am concerned than communicating and that’s what Ronnie knows all about.’

In the presidential election of 1980, Reagan had defeated Jimmy Carter, who, while he could get his head around the detail and always stayed true to his principles, couldn’t deliver a line like the old actor he was up against. With her hair and voice moulded for the television age, Thatcher, too, was a far more vivid presence that the Labour leader Jim Callaghan and certainly his successor Michael Foot. She got, too, that leadership meant performance.

Heston talked so much about politics that I asked him why he had never himself stood for elected office. ‘I haven’t the temperament for it and I certainly haven’t the patience,’ he growled. ‘I’d almost certainly have ended up decking some of my opponents, and, frankly, they’d have deserved it.’

If he’d lived to see this day, Heston would almost certainly have approved of the way his country was being run – and ours, too, for that matter – but I doubt if it would have made him any less angry. There would still undoubtedly have been the gnawing sense of grievance that the critics never accorded him the respect he felt was his due as an actor.