Ahead of a major conference in Britain, Esperantist TIM OWEN explains how the language arrived in the UK.

One hundred and fifteen years ago there was an event in Dover, a coming together of both sides of the Channel. The participants were new Europeans, if you will – individuals who had taken somewhat revolutionary steps to find a way round a cause of division between people.

They were speakers of Esperanto, a language designed for international communication. In the early days of wireless telegraphy and ocean-crossing steamships, the question of which language to use internationally was up for discussion and they had an answer.

Esperanto gained its first 1,000 adherents within two years of it first being published in 1887 (as a planned, rather than natural, language it has a birthday – July 26, 1887), though only nine of those were from the northern side of the Channel.

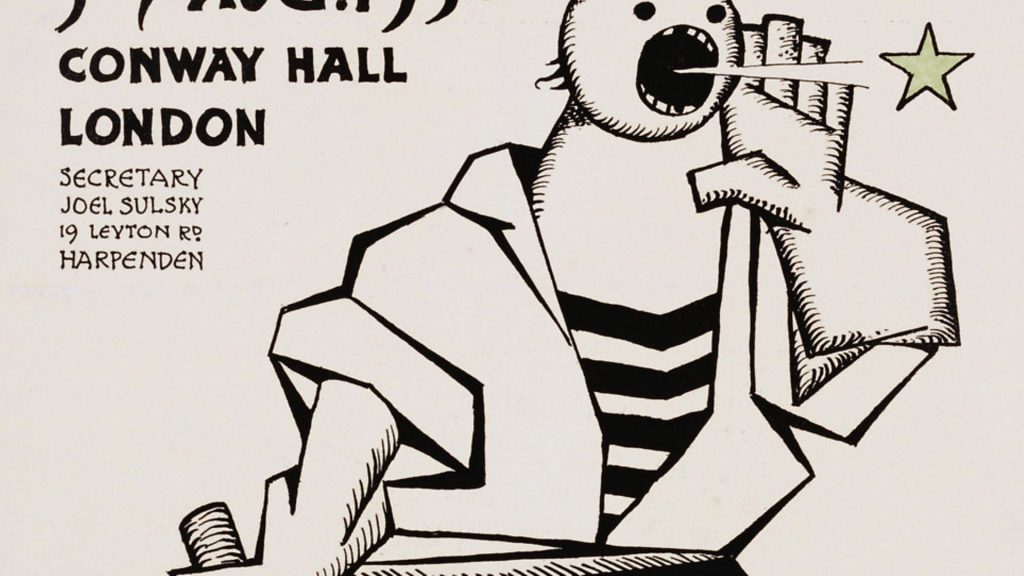

The first club in these islands wouldn’t be formed until 1902, in Keighley. The first magazine, The Esperantist, was founded the following year, at the behest of the campaigning journalist WT Stead, who agreed to financially back it. (He didn’t need to; the magazine proved to be profitable.)

Everybody involved in the nascent movement was a beginner, an amateur with conviction, engaging in it against the odds because it was something they believed in.

It was in 1904 that these pioneers did something remarkable: they organised an international get-together on British soil, even in the absence of a national Esperanto association, they would get around to setting that up a few months later. A few enterprising souls had led the way with small-scale visits to Esperanto groups across the water, one to Boulogne at Whitsuntide (12 British Esperantists making the trip) and some more at the invitation of the local group in Le Havre on July 30, when a small delegation arrived to a warm welcome, escaping the day’s rain with around 50 Esperantists gathering in the Town Hall for a concert.

It was around this time that an Esperanto group formed in Dover.

Within a few weeks, it had invited groups from northern France to come to a reception of foreign Esperantists at the Town Hall, proposed by the mayor, Sir William Crundall, coinciding with a motor boat race from Calais to Dover on August 8.

And come they did, though with an hour’s delay because of the boat race, the French taking the honours. They visited Dover Castle, sang translations of each other’s national anthems, took a special tram to the Town Hall (which featured a sign bearing the message ‘Bonvenon!’ outside), and enjoyed their evening concert.

What was really notable at this first international Esperanto gathering in the UK is what came afterwards. And to tell that story, we have to go first to a couple of days before.

Three British Esperantists took the reverse journey, crossing from Dover to Calais and spent the weekend there with around 70 local Esperantists. One of the travellers was Harold Bolingbroke Mudie, editor of The Esperantist and the first president of the World Esperanto Association, which would be formed in 1908 and which he would lead until he was killed in France in 1916. He was serving in the military at the time, but his death – at the age of 35 – was the result, not of enemy action, but his car being struck by a train at a level crossing.

During his short life, Mudie was the most active pioneer in this country, and it was during discussions in Calais that the lawyer Alfred Michaux, a member of the group in Boulogne, proposed building on the smaller event by hosting a huge international one the following year. This event in Boulogne was the first World Esperanto Congress, attended by 688 people from 20 different countries, and not a single interpreter needed.

The language’s creator, the diminutive Ludwik Lejzer Zamenhof, a Jewish ophthalmologist who began working on the language when he was a boy growing up in Bialystok, summed up the mood perfectly, stating that standing within the welcoming walls of Boulogne were ‘ne angloj kun francoj, sed homoj kun homoj’ (‘Not Englishmen with Frenchmen but people with people’).

The event proved a resounding success. Zamenhof sent Michaux a postcard of the two of them bearing the message ‘Kion disigis ne unu miljaro, tion kunigis Bulonjo-?e-Maro’ (‘What not even a millennium had managed to tear, was brought back together at Boulogne-sur-mer’). The World Congress became an annual event, swelling to 6,000 people from 73 countries celebrating Esperanto’s centenary in Warsaw in 1987.

This year happens to be another one hundredth, this time of the UK’s national conference. The first was held in Edinburgh in 1908 and it’s been a traditional part of the Esperanto calendar, usually being held in April, since then. The jubilee one will therefore occur in April 2019. The script writes itself, doesn’t it?

Where else could the Esperanto Association of Britain choose to host its jubilee conference than Dover? What else could it do but defy Brexit and run a day trip to Calais, the location where the idea of the World Esperanto Congress was born? And what better way to underline that today’s Esperanto speakers are still ‘ne angloj kaj francoj, sed homoj kun homoj’ than by repeating the offer of those early pioneers and inviting their friends from across the sea to come over? The French have folded their own national congress into the British event. At a time when the UK is being pulled away from Europe, the neighbouring Esperanto associations are coming together.

The Kunkongreso de Esperanto (Joint Esperanto Conference) will open on April 12 and close on the evening of the 15th with a convivial group meal. The entertainment won’t quite be like it was 115 years ago. Where their singalongs consisted of national anthems, the 2019 version has a concert from a Swedish Esperanto singer. The pioneers danced a waltz; this year’s participants will enjoy a ceilidh on the opening night and another concert on Monday.

Entertainment before was reading out telegrams from abroad; the people gathering in Dover will have a quiz, a documentary in their language, several presentations, and a discussion circle about the most pressing political topic of the day.

But some things never change and now, as it was then, it will all boil down to being homoj kun homoj.

• Tim Owen (@meddysong) is director of the Esperanto Association of Britain and co-author of the new textbook Complete Esperanto

• You can find out details about the Esperanto Association of Britain and Espéranto-France’s Kunkongreso at the event’s site, britakongreso.org.