Brexit started a destructive process that has spread far beyond Britain’s shores and the single market – it has destroyed an idea

Brexit has been the very first trauma of my political life. When I said this on Twitter, I just got sarcastic comments. I was a sissy, a wimp, I knew nothing about life, I had no idea of geopolitical issues. What about the Syrian massacres? They asked. The Bosnian war? Or the French suburbs orchestrated in ghettos? No, sorry, these have nothing to do with my point.

Whether or not we are indirectly responsible for wars, or for a series of political mistakes, they are not the result of a democratic vote. Ok, I could have mentioned the ‘non’ vote in the French referendum on the European Constitutional treaty, in 2005, which actually foreshadowed the whole story to come, in which the victory of Donald Trump happens to be, undoubtedly, the second horrific chapter. But Brexit was the first democratic vote I witnessed, where the consequences directly affect Europe, France, my country, my universe, my political and mental landscape, me. The biggest trauma of my half-century life.

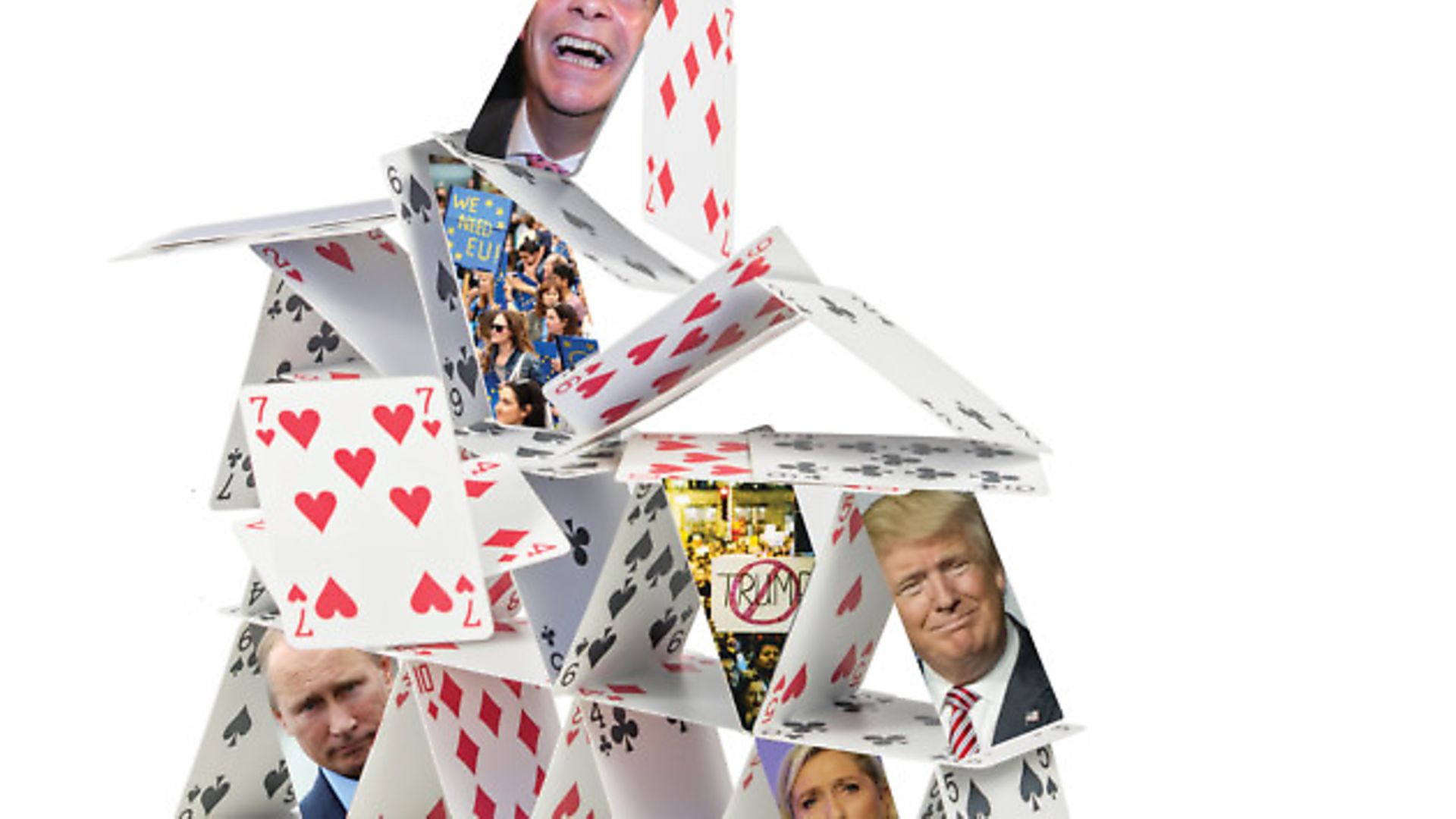

I won’t forget that early morning of June 24 in Berlin, where I was when I found out. I had quietly fallen asleep with the last polls predicting a Remain victory. What a shock. The image of a house of cards just about to fall. A premonition of a series of catastrophes to follow. I had set my alarm clock for 6am, so I would know first thing. And I stayed in my hotel bed like a mummy, frozen.

Why was I in such a daze? After all, it was just a broken contract between Britain and us. It was not going to change anything in our daily lives. ‘Are my friends on another continent now?’ asked a little boy who had spent his first few years at school in London. No, boy, they are still on the same continent. Eurostar will still take the same time to get there, things will remain like they were. We can even think they might get better for us, on this side of the Channel: we Europeans will take advantage of companies and banks moving out of the UK, which already began to happen, since their main attractiveness was to be located in the European zone. We will benefit from the collapse of the pound, which didn’t take long to start. From the decline of the British economy, from the end of the City’s golden years.’

Yet something more fundamental has died. What exactly? It’s difficult to define. It’s a bit like when you are at the theatre, and then, as light returns to the stage, a new set has appeared that makes you feel inexplicably uncomfortable. The Brexit vote was preceded by the murder of a pro-European MP, Jo Cox. It was followed by the murder of a Polish worker and attacks on immigrant groups. Some French people who live in London are being insulted. It has got to the stage where some foreigners dare not speak in the street any longer. Racist and religious related aggressions have increased. I fail to see that it could be by chance, but rather believe that it’s both an omen and a symbol.

No, it is not just a diplomatic and economic affair. What Brexit carried away goes much further than single market. It has destroyed an idea. An atmosphere. A world. A journey we started 60 years ago, to overcome fratricidal wars and mass crimes, is set, tragically, to be ended. The UK is now the most obvious victim of Brexit, but it may swallow us all. Europe was already in a demographic decline. By disintegrating, it will lose its last way to face great world powers which for the most part do not share its values: democracy, rule of law, public freedoms. Little wonder that Putin looks so pleased. First Brexit. Now Trump.

Brexiters do have cause for complaint. The world is not perfect. Europe is not perfect. Economic neoliberalism has produced inequalities. Elites are not exemplary. Public services are deficient, minimum pay insufficient, mass immigration scary, globalisation unfair, creating both wealth and outcasts, raising some countries out of poverty, but plunging others into instability.

Ask people if they wish to carry on like this and they will answer ‘no’. When the British people were asked if they wished to stay in the EU, the question that many heard was: ‘do you want things to continue like this?’ « No » It is always the same with referenda, that illusion of democracy. They make one believe that a complicated issue can be answered by a ‘yes’ or a ‘no’. People often answer the questioner, not the question; the context, not the text. Many Brexiters did not say ‘no’ to the European Union, they just said ‘no’.

A few weeks ago, here and there in London, I talked to a few Brexiters. One regretted his vote now that he could measure the damage to the UK economy. Another was delighted to be « free at last », to be « rid at last of Brussels and its laws ». Me : « In what way has the EU been an impediment in your everyday life ? You were given opt-outs on nearly all common regulations. » He : « For example, we Brits are unable to send a criminal or terrorist back to their country of origin, if the individual could face torture there. » Me : « It is international agreements signed by Britain that prevent this, not Europe! » He : « And we will get rid of those laws which block our economy. » When I tried to tell him that all European decisions must be approved by the leaders of each country or by national parliaments, he sighed disbelievingly. In desperation, I went on: ‘Brexit leaders have won on promises that proved to be enormous lies, such as the weekly £350 million for the NHS. Doesn’t that bother you ?’ And there came back that terrible answer: ‘Yes, they lied. So what? All politicians lie.’

My 14-year-old daughter, tired of listening to me bitching away with my an obsessive indignation about this Brexit story and the lies that allowed the Leave campaign to win, told me: ‘You said that Francois Hollande lied during his political campaign, but you still voted for him! British people just did the same.’ This left me pensive. The Brexit campaign will go down in history as the most phenomenal lesson in political cynicism ever. Political campaigns will always carry their lot of promises and lies to different degrees. But the Brexit cheerleaders pushed the logic of that tactic to a new extreme: Our time has become nihilist to an extent that facts are not taken into consideration any more. The less you believe in politics, the more you appreciate the personalities who ridicule and defy it. The bigger the lie is, the more the liar is perceived as a hero. Johnson, Farage, Trump. No wonder ‘post-truth’ has been chosen by the Oxford Dictionary on both sides of the Atlantic as the ‘new word of the year’.

I never thought that the politics of Marine Le Pen would win in Britain ahead of France. At home we are sadly used to hearing foul-smelling songs of populism, with eternal refrains about plots from the elites, the media, the politicians, the establishment, the system. Nationalist and xenophobic and all-phobic gangrene, which plays on fear and hatred, has been making gains in all our Western democracies, in France, Italy, Hungary, Austria, The Netherlands, Scandinavia, Poland and even the United States. Germany, we thought, would be immune because of its history. As for Great Britain, it was quite simply unthinkable. Even Nigel Farage made sure to keep his distance from fellow MEP Le Pen at the European Parliament, knowing how much she was seen as a scarecrow in his country.

Yet it is the UK, the most ancient parliamentary democracy, with its love of debate, its creativity, its passion for freedom, that happens to emerge as Europe’s first Le Pen-ist state. Theresa May, with her distinctive footwear and her urbane, subdued smile, has very politely fooled us all. Obsession with immigration, nationalist withdrawal, the prospect of a protectionist state, sneering at Brussels, attacks on the global elite, the dismissal of the 48% who voted (as she did) Remain… your Prime Minister, frankly, has at times seemed like Marine Le Pen in all but name. May was even about to overtake her model, British buisinessmen having been furtively asked to count their foreign employees. For her part, the real Marine Le Pen has a Brexit poster hanging in her office at Front National HQ, like a personal hunting trophy… or a lucky charm to help her through next year’s French presidential elections.

And suddenly came November 9. Trump. The logical next stage in the huge house-of-cards breakdown. The explosion of that gigantic underlying wave of resentment that neither polls nor experts saw coming. Until this year, November 9 was remembered for marking a great anniversary: the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, the dislocation of the USSR, the death of totalitarianism, the end of the Cold War. What an irony of history that the start and end dates of global liberalisation both fall on November 9, 27 years apart. The intervening years have seen the Western democracies shaken by two major events: the attacks of September 11, 2001, and the financial crisis of 2008. Inequalities and divisions have deepened. Demography has changed, the world’s major power lines have tilted, white people are panicking, seeking escape, refuge in a nostalgic past, only the good parts of which they remember. The usual scapegoats are dragged up: free trade, ‘elites’, above all foreigners, immigrants, refugees.

Brexit, Trump, Le Pen. The same angers, same fears, same racist whiffs, same leaders, same lies. Brexit is not just a British story, it’s ours. The thingummy called Johnson-Farage is nothing but the failed version of Trump. The thingummy couldn’t quite reach the top. Trump, taking the face of modern populism further, has done so. Like Le Pen, he has understood how chaos can be an instrument for power. And how lies, no matter how obscene, are a lot more audible that truths. Where he has led, Le Pen hopes to follow. Brexit helped them both. What’s not to be sad about ?

Marion Van Renterghem is a reporter-at-large at Vanity Fair, after 30 years with Le Monde