The US and Russia endured very different years between the two world wars. But for both, these were troubled times when art helped shape great social change.

There are two exhibitions on at London’s Royal Academy, each presenting a contrasting perspective on the visual expressions of the interwar years in the US and Soviet Russia. This was a period when artists, designers, and writers represented and even helped to shape epic social transformations.

In Russia, the successive five-year plans aspired to create a modern Communist society at lightning speed from the wreckage of the First World War, the Revolution, and the Civil War, whatever the (eventually dire) human cost. By contrast, the New Deal in America was a restorative effort to salve a country in economic depression, a lost nation reeling in the aftermath of the Wall Street crash.

The confluence of these two shows couldn’t come at a more appropriate time. The blurred line between official and unofficial dialogues between American and Russian political figures is once again the subject of intense scrutiny. The Royal Academy’s two shows allow us to dive into the history of these relations at their most vivid: the troubled times of the 1920s and 1930s.

The pairing also serves as a reminder of the power of public art in an age when state-funded culture in America is under threat and art speculators, most notoriously Russian oligarchs, persist in fostering a market of engorged prices.

The Russian art show is a fittingly giant exhibition that amasses a welter of early Soviet visual culture, from paintings to porcelain, photographs, films, and even a full-size recreation of an apartment designed by El Lissitzky, a leading avant-garde polymath who worked in numerous media.

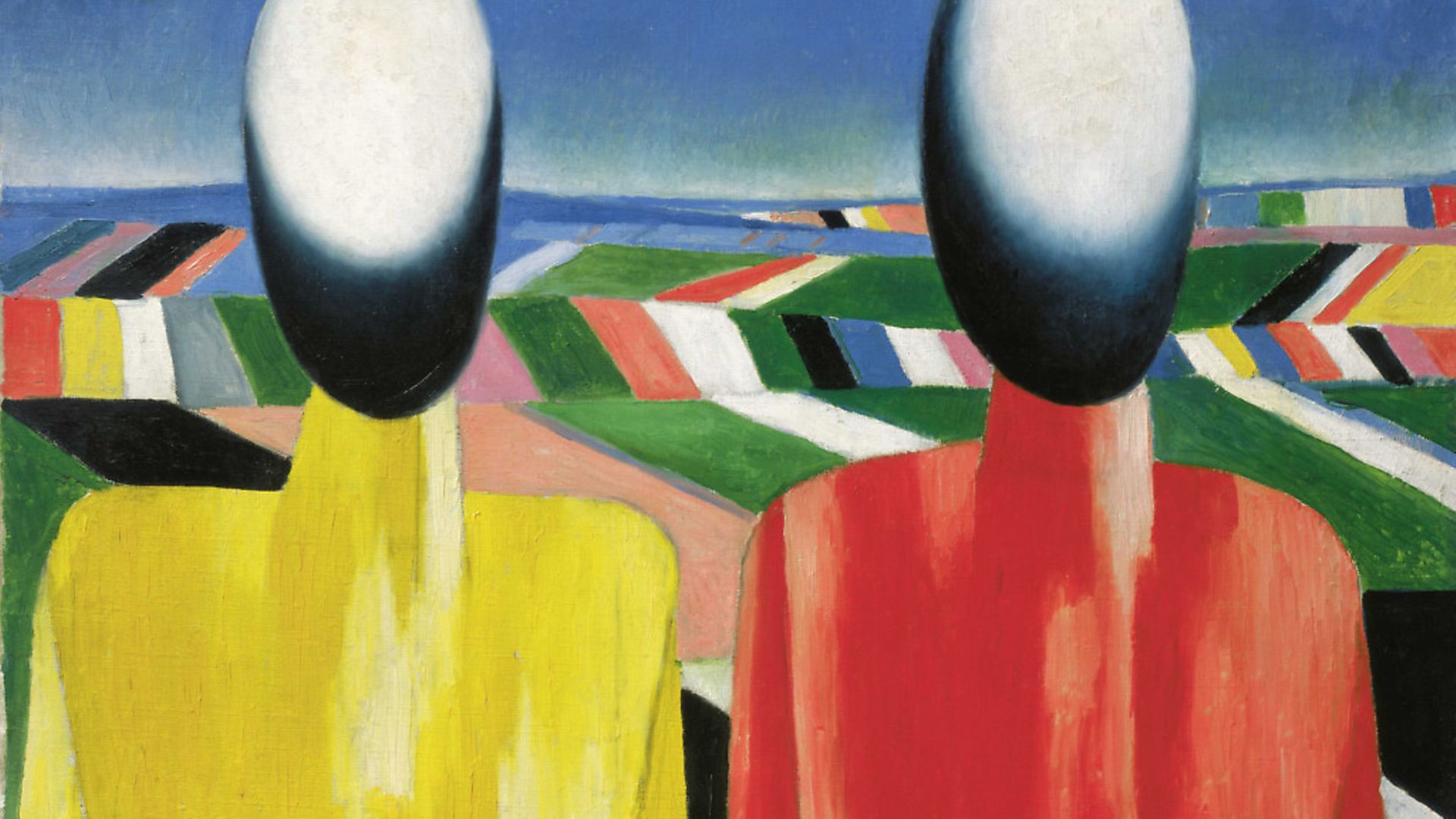

An alternative title to the exhibition could be ‘Russia Before the Fall’: the timeframe (1917-1932) pointedly limits the scope to the years of post-revolutionary experimentation prior to Socialist Realism’s orthodoxy and the descent into tyranny (although the malignancy of Stalinism was already pervasive by 1932). Spectators walk through a giddying rendition of the cultural explosion of the Revolution’s first decade. In this early period, efforts to construct a new world manifested in countless modernist icons of leaders and workers – and in the abstract shapes and hues of the Constructivists, who aspired to create an original Communist lexicon.

The exhibition shows the full range of Soviet painting and graphic arts, from the increasingly precarious avant-garde, who tried to reconfigure art as production, to painterly landscapes celebrating Mother Russia by easel painters. Crucially, these works are situated alongside works in other media in a way that appropriately acknowledges the diversity of Soviet culture – for instance, combining Pavel Filonov’s painting of a female farm manager with Arkadii Shaikhet’s photographs of collective farms.

In the final room stands a melancholy finale. A free-standing chamber contains projected arrest cards of the purged – including many artists, directors and writers – underscoring the sense of dashed dreams. In an adjacent room, Tatlin’s unwittingly tragic Letatlin, a winged appendage for a flying man, twirls solemnly in the rotunda, the useless apparatus of a Soviet Icarus casting haunting shadows.

Ultimately, the exhibition provides a multifaceted, if somewhat overwhelming, portrayal of the Utopian bid to fashion a red planet (as specifically depicted in a painting on display by Konstantin Yuon).

By contrast, the American show assembles paintings from America’s lost decade, when the troubled times of the Great Depression witnessed unprecedented unemployment, breadlines, evictions and the ecological calamity of the Dust Bowl.

The exhibition offers a well-chosen sample of paintings that serves as an excellent primer to the assorted styles of the era by familiar and lesser-known artists. There are the sharp-lined industrial scenes of Charles Sheeler and Charles Demuth, the elegant abstractions of Georgia O’Keeffe and GLK Morris, the ribald social realism of Reginald Marsh and Paul Cadmus, and respectively optimistic and harrowing tributes to black experience by Aaron Douglas and Joe Jones. The show confirms the substance of American modern painting before abstract expressionism, although a fearsome image by the emergent Jackson Pollock feels like an outlier.

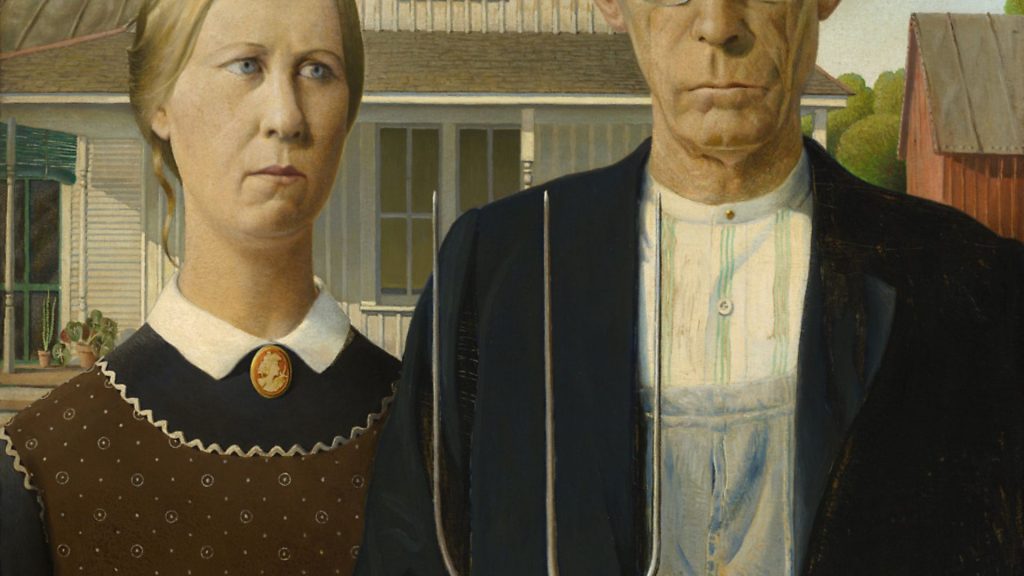

The presence of Grant Wood’s 1930 American Gothic has dominated reviews – and an accompanying text asserts that the work is arguably the most important of the era. Yet this barbed, even uncanny, image of rural folk of uncertain kinship (not really the nostalgic paean to regional folksiness it seems – I heard a young visitor call it ‘creepy’) is hardly the most representative picture of the Depression. It might just as well have been made in the 1920s. Edward Hopper (whose 1940 Gas, also eerily timeless rather than timely, is on display) and Charles Burchfield had long been exploring such peculiarities of American vernacular idioms.

A more symptomatic image, albeit one less likely to invite countless parodies, is Philip Evergood’s Dance Marathon. This ghoulish vision of desperation shows the weary contestants of the dehumanising competition of the Depression in distorted expressionist forms.

It is not strictly fair to compare this smaller US exhibition of paintings with the gigantic, multimedia Soviet show. A juxtaposition of the two exhibitions could invite the conclusion that in the 1930s American individualism contrasted with the Soviet mass mind – and such an outlook could easily be countered.

But the similarity with which the machine age is idealised in America and Russia is notable – representations of their respective factories and workers are often analogous, though the Russians betrayed a masochistic tendency to fetishise labour.

There is also synergy in the largely unofficial dialogue between American and Russian cultural figures in the 1930s. An international ‘red network’, to appropriate the anti-leftist Elizabeth Dilling’s phrase, extended from Moscow to Mexico City, constituting an alternative transatlantic traversal to the ‘American in Paris’ myth, in which New York and Berlin were staging posts in a transnational journey. Americans looked at Russians looking at America with fascination.

And so the recent scandalous communications mark only the latest addition to an intricate, confusing tapestry of exchanges evincing curiosity, emulation, suspicion and conspiracy. At the Royal Academy (shaping up as a leading venue for historically-themed exhibitions of revolutionary art), the silent conversations between these American and Russian neighbours tell stories of world-changing narratives in more similar ways than one might imagine.

Barnaby Haran is lecturer in American Studies at the University of Hull

Revolution: Russian Art 1917–1932 is on until April 17

America after the Fall: Painting in the 1930s is on until June 4

This article first appeared at www.theconversation.com