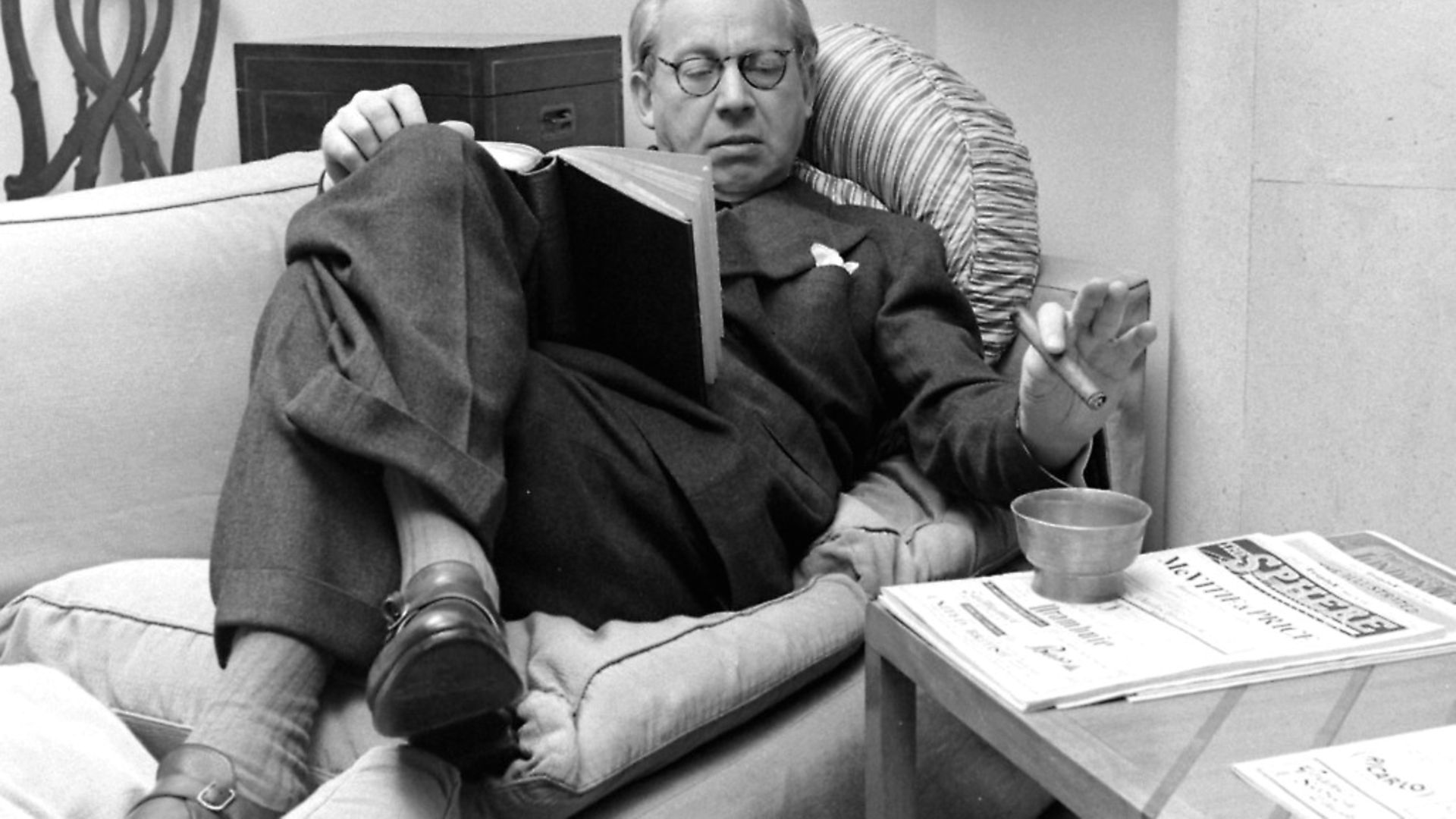

CHARLIE CONNELLY remembers the life of the first director to receive an Academy Award outside of Hollywood, who shaped views of Britain.

Think of Henry VIII and the chances are you’ll think of a larger-than-life cross between Falstaff and the Goodyear blimp sitting at a banqueting table, tearing at a chicken leg with his teeth and tossing the bones over his shoulder. It’s one of the archetypal images of English history passed down through the centuries; almost the summation of a dawning golden age when England would become a major force in the world. It’s also a complete fiction perpetrated by a Hungarian émigré who’d barely been in the country a year when he came up with it.

Director Alexander Korda’s The Private Life of Henry VIII was released in 1933 with Charles Laughton as the eponymous monarch. Korda had noted Laughton’s talent and been determined to find a suitable starring role for him. According to some sources it was when he noticed the actor’s resemblance to a statue of the Tudor king that he conceived a film that would change British cinema and enshrine his perception of English history’s most recognisable monarch forever. Laughton enjoyed himself immensely in the role, chewing the scenery in the same way his character chewed the poultry, and produced a performance of such technique and presence it won him an Oscar for best actor, the first time an Academy Award had ever gone to a film made outside Hollywood.

Making The Private Life of Henry VIII had been a huge risk for Korda. He was newly-arrived in the country and had to fight a prevailing attitude that period films didn’t work in Britain. This perceived risk meant a small budget that might have proved crippling for a lesser director, yet Korda turned out a film of the highest quality that proved a smash hit with the critics and at the box office. It ran for an almost unprecedented nine weeks after its premiere at the Odeon, Leicester Square, and went on to gross more than half a million pounds. The film gave enormous career boosts to Laughton and co-stars Merle Oberon and Robert Donat and inspired pioneering British film critic C.A. Lejeune to hail it as “more likely to bring prestige to the British film industry, both at home and abroad, than anything we have done in the whole history of film-making”.

Across the Atlantic, American audiences lapped up Laughton’s Henry too, prompting United Artists to grant Korda a 16-film distribution deal. British cinema had truly arrived on the global stage and Alexander Korda was leading the way.

Such success forged largely on his own terms allowed Korda the opportunity to settle at last. A brief period working in the US during the Second World War aside, he would spend the rest of his life in Britain, taking out citizenship and playing a major role in boosting bomb-damaged morale with a succession of patriotic productions. The period of rootless displacement that had characterised much of his adult life was over.

He was born Sándor László Kellner in the Hungarian village of Pusztatúrpásztó where his father managed a large estate. Shortly after his father’s death, which plunged the family into poverty, the teenage Kellner moved to the capital Budapest and fell in love with film, writing reviews for newspapers under the name Korda – from the Latin phrase sursum corda, meaning ‘lift up your hearts’ – and taking a job as a runner at a film studio.

Excused military service on account of his myopia, Korda rose to become a script writer and, by 1915, a gifted director of boldness and vision.

Hungary endured a tempestuous period after the war and the related collapse of the Austro-Hungarian empire. Korda tried to make the best of it, continuing to make films during the four-month 1919 Hungarian Soviet Republic and being appointed head of its film directorate. Among his politically-expedient productions was the overtly anti-aristocratic historical epic Ave Caesar!. But when the communist regime collapsed to be replaced by the brutal counter-revolutionary government of Miklós Horthy, his fortunes changed dramatically. In October 1919, the anti-communist reprisals began in earnest and Korda was among those arrested and taken to Budapest’s Hotel Gellert, the headquarters of Horthy’s heavies, where Jews and communists were regularly interrogated and frequently murdered. Somehow, despite what would have been seen as a leading propagandist role during the short-lived Republic, Korda was released, fleeing to Vienna with his actress wife Maria.

Taking a job at the Austrian capital’s Sascha-Film studio, bankrolled by Count Alexander Kolowrat, Korda’s first production was a lavish adaptation of Mark Twain’s The Prince and the Pauper that met with great critical and commercial success on both sides of the Atlantic. However, Kolowrat’s insistence on interfering with his directors’ creative visions irritated Korda to the extent that he left first the organisation then, after the failure of his independent film Samson and Delilah, the country. He moved on to Berlin in 1922 before, at the end of 1926, crossing the Atlantic for Hollywood.

He made an immediate impression with The Private Life of Helen of Troy in 1927 but that success just led to offers of more template historical epics. Korda found the Hollywood studio system increasingly frustrating and, after a brief spell in France, relocated to Britain in 1932 to found London Films, the company with which he would truly make his name. Britain offered Korda a balance between the artistic freedom of the European cinema industry that had made him and the rampantly commercial philosophy of Hollywood in a way that suited him perfectly. The success of The Private Life of Henry VIII allowed the director to build his own studio complex at Denham in Buckinghamshire where as well as Laughton, whom he’d made into a major international star, Korda was able to secure the services of Marlene Dietrich, Douglas Fairbanks, John Gielgud, Laurence Olivier and Vivien Leigh.

It wasn’t non-stop success – an attempt to recreate the Henry VIII formula with The Private Life of Don Juan fell short, and allowing H.G. Wells full creative control on Things to Come produced a dreary piece of cinema – but Korda was already building something more than just British film.

The Private Life of Henry VIII was a favourite of Winston Churchill who, during the early 1930s, found himself out of favour politically. He and Korda became friends through a shared love of cinema and a romanticised view of British history, prompting the director to engage Churchill as a screenwriter at Denham. He paid the future prime minister a hefty £10,000 for two screenplays, one a history of aviation, the other a jingoistic production called The Reign of George V. Neither was ever made but the pair forged an alliance that arguably helped to set the course of 20th century British history.

Churchill’s one criticism of The Private Life of Henry VIII was that it could have benefited from “a little less chicken bone-chewing and a little more England-building”. He had, however, particularly enjoyed lines like, “Diplomacy, my foot! I’m an Englishman, I can’t say one thing and mean another. What I can do is to build ships, ships, and then more ships!”

As tension mounted in Europe, 1937’s Fire Over England, in which Queen Elizabeth sends out fire ships to counter the Spanish Armada, was deliberately timely.

In Korda, Churchill recognised a man who could realise his quest to turn history into meaningful, didactic stories in order to build a particular sense of nationhood that would unite its people and send a message to the world. So potent was the cinematic propaganda that when Korda temporarily relocated to the US during the early part of the war to complete filming on The Thief of Baghdad, the FBI investigated him as a possible British agent at large in the then neutral USA. In some quarters it was whispered that Korda was to the prime minister what Leni Riefenstahl was to Hitler. Churchill, meanwhile, called Korda “the only honourable man in the world of film”.

The version of British history concocted and screened by Korda helped create an image that endures today, one for which he was knighted in 1942. When he wrote a letter of thanks for the honour to the prime minister he was sure to quote Robert Browning’s Battle of Trafalgar poem, Home Thoughts, from the Sea. “Here and here has England helped me,” it read. “How can I help England?”