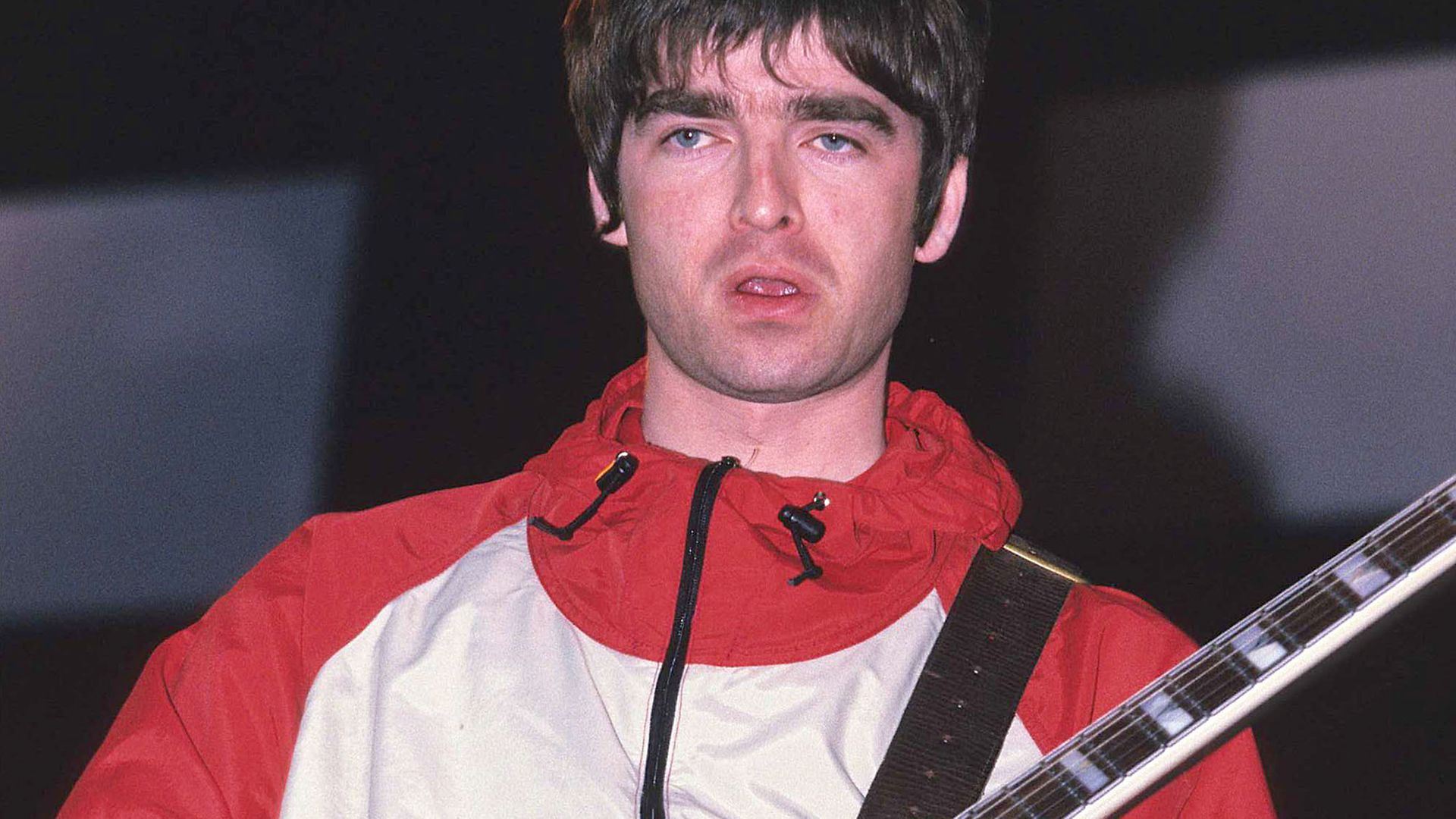

Britpop, I imagine most of you are old enough to remember, was a loosely applied umbrella tern referring to the movement of varyingly retro British guitar bands which rose to dominate the UK pop charts in the mid 1990s. I was in my mid 20s at the time – pretty much the same age as most of the stars of Britpop – and it was a ‘scene’ which I found exciting and annoying in more or less equal measure.

The thing I’d found exciting about the movement was its unexpectedness: I remember, back in 1993, a year or so before the advent of Britpop, reading an article in one of the music papers which stated, with a degree of confidence, that the era of the pop star was over.

The charts back in 1993, you may recall, were dominated by literally faceless DJ/producer collectives with names like car number plates producing reggae-inflected dance hits. The last gasp of the pop idol, the article insisted, had been that onslaught of fresh-faced Australian soap stars trotting out interchangeable Stock Aitken and Waterman-produced lightweight disco singles, which had all but monopolised the charts since the late 80s but which was finally running out of steam (apart from Kylie, who, unbeknownst to us at the time, would turn out to be ageless and possibly immortal, but that’s another article). That was it, the article declared: no more pop stars, and henceforth we’d have to make do with the aforementioned faceless dance collectives.

Eighteen months after that article was published, the biggest thing in pop music was British guitar bands. Just goes to show you have no idea what’s coming.

Paradoxically, while the most exciting thing about Britpop was its unpredictability, the most depressing thing about it, for me at least, was its inevitability.

My generation – the ones born in the early 70s – had grown up being bombarded by nostalgia for the 1960s. We spent our entire childhood and early adolescence being taunted by images of this only-just bygone halcyon era of excitement, innovation and sheer coolness which we’d managed to just miss.

It was probably even harder for those of us who grew up in Liverpool, which had been the source of so much of the 1960s’ excitement and which was now, in our lifetime, enduring perhaps the roughest era the city had ever known, but I think my whole generation felt this sense of loss to one degree or another.

So it was perhaps to be expected that when it was our turn to do something with our own ‘scenes’, many of us chose to spend our 20s trying to re-create the 1960s. Because that’s what Britpop – and the ‘Cool Britannia’ subculture which grew up around it – really was: a transparent attempt at a Swinging Sixties reboot, even down to the confected rivalry between Oasis and Blur being a blatant knock-off of the (equally confected, while we’re here) Beatles vs. Stones feud.

At the point at which my lot were supposed to be innovating and experimenting, many of us opted instead for what would now be called ‘Swinging Sixties Cosplay’ and spent the whole time trotting out inferior rip-offs of a previous generation’s achievements.

I was thinking about this the other day when I was reflecting on how often the Second World War in invoked both by Brexiters and anti-maskers/Covid sceptics, shrinkingly few if any of whom are actually old enough to remember the war. And it struck me: it’s the same thing.

Their feeling of having grown up in the shadow of a previous generation, who did all the things you wish you could have done (even if you know you might not have been smart or brave enough to do them). That sense of inferiority being reinforced by constant cultural reaffirmation of just how much more important the challenges faced by your forebears were than any of the paltry inconveniences afflicting you (much as my ‘people’ were surrounded by retro-60s nostalgia, the Boomers grew up in a welter of heroic war movies and harrowing documentaries). That overwhelming desire to emulate the achievements of one’s predecessors, and the tendency to confuse emulation with imitation.

Just as my fellow British Gen X-ers reacted to having missed out on the 1960s by trying to recreate the 1960s for themselves, many British babyboomers seem to be reacting to having missed out on the war by, if not exactly starting their own war, adopting the terminology and attitudes of wartime, even if it’s perilously inappropriate. That’s why they’re so hung up on the whole “Plucky Britain stands alone” thing, at a time when Britain doesn’t have to stand alone (and was not ‘alone’ in wartime) and (it’s increasingly apparent) couldn’t stand alone even if it wanted to.

The difference, I guess, is that while the 1990s’ fixation with the 1960s just produced some interesting records (and some deathly dull ones), the current obsession with wartime resilience is likely to, quite needlessly, produce the kind of hardship that requires such resilience. And that really is crazy.