CHARLIE CONNELLY reports on the life of Rudolf Nureyev, a figure drawn into Cold War politics and known for his appalling behaviour as well as his supreme gifts.

1961 brought an extra chill to the Cold War. In January outgoing US president Dwight D. Eisenhower had severed links with Cuba and in March Britain convicted the five members of the Portland spy ring. The Soviets meanwhile were taking the lead in the space race, a position cemented in April when Yuri Gagarin became the world’s first astronaut. On June 4 newly elected US president John F. Kennedy met with Nikita Khrushchev in Vienna for talks dominated by the division of Berlin. Two months later work would start on the construction of the Berlin Wall.

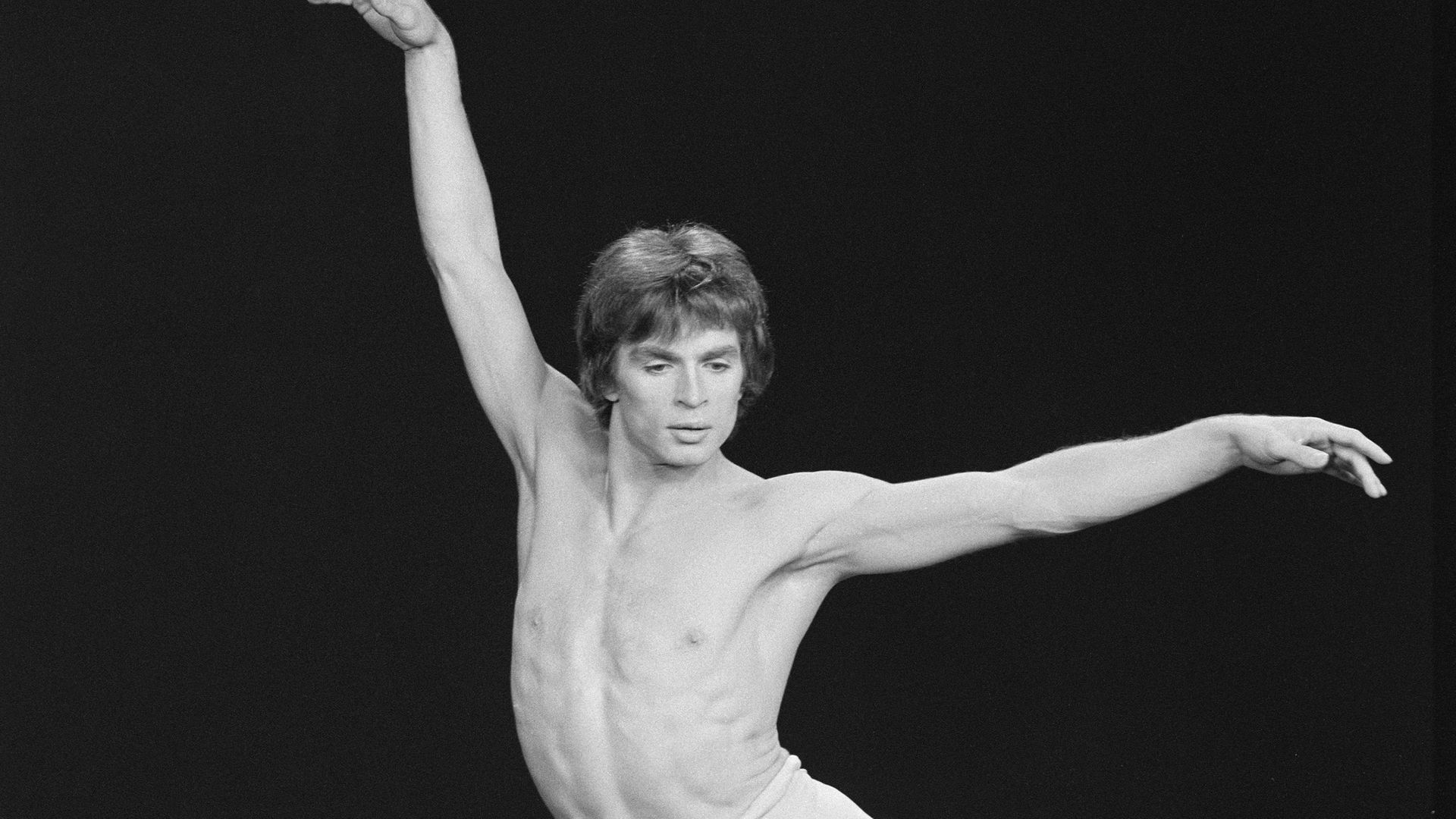

On June 14, just over a week after the end of the Vienna summit, the 120-strong Kirov ballet company arrived at Le Bourget airport in Paris ready to fly to London for the second leg of a high-profile tour designed to prove the USSR was leading the way in cultural as well as scientific affairs. Its star male dancer, 23-year-old Rudolf Nureyev, had thrilled Parisian audiences with his grace, physical prowess and intense artistic and personal charisma. This was a dancer like the world had never seen.

Nureyev’s was also a personality like the world had never seen. Headstrong, short-tempered and with an unshakable self-confidence that often manifested itself in outrageous displays of arrogance, he was quite a handful for his Soviet minders. Wilfully disobedient, he embarked on spontaneous unchaperoned shopping trips in the French capital and enjoyed the city’s nightlife without permission, mixing freely with the French social elite and sampling the city’s gay clubs with vigorous enthusiasm.

As the dust settled in the aftermath of the Vienna talks the Soviets decided Nureyev, for all his prowess and prestige, was too much of a liability to remain outside their borders. As the dancers milled around the terminal Nureyev was taken to one side and informed he was no longer going to London. Khrushchev himself had recalled him to give a special performance in Moscow instead, he was told, and a chartered plane was waiting to fly him back to the Soviet Union.

Nureyev knew what this meant. The Kirov had hesitated about bringing him on tour in the first place but his reputation had already spread beyond the Iron Curtain. There was no question of leaving him behind, but his enthusiastic embrace of western decadence meant they were now sending him home. There was no ‘special performance’ planned, Nureyev was going to be punished; at best seeing out his career going through the motions in draughty concert halls in provincial Soviet backwaters, at worst a prison sentence.

The news raced through the company. Someone made it to a payphone and called Clara Saint, a Parisian socialite with whom Nureyev had struck up a friendship. Pausing only to notify the French police Saint jumped into her car and sped towards Le Bourget, praying she would arrive in time.

Rushing into the terminal she found a glassy-eyed Nureyev sitting in a bar flanked by two KGB men. She rushed over, embraced him on the pretext of saying goodbye and whispered that two plain clothes policemen were standing right behind her. Nureyev stood up and walked briskly towards the officers taking six paces, a short enough distance to reach them and claim asylum before his handlers realised what was happening. They leapt to their feet and attempted to wrestle the dancer away.

“Ne me touch pas!” shouted one of the French officers. “Vous êtes en France ici.”

It hadn’t been planned, it was practically a spur of the moment decision, but Nureyev’s defection sent shockwaves around the world. His was an act all but unprecedented. Defections of any kind were rare in 1961 and he was certainly the first high profile cultural figure to escape to the west in a huge blow to Soviet prestige.

In the course of those six steps across Parisian linoleum Nureyev became a symbol of something much larger than an ambitious dancer. He was now a key piece in a high-stakes game of international chess. It needed someone of particular resilience to survive the global attention, someone with the self-belief to embrace and transcend an international spotlight in which some might shrivel. It needed Rudolf Nureyev.

He had already overcome considerable obstacles even before Paris, having been born on a train crossing Siberia and growing up in Ufa, Bashkortostan, in a family so poor he spent most of his childhood without shoes. He fell in love with ballet at the age of seven when on New Year’s Eve 1945 his mother snuck the whole family in to a performance of Dance of the Cranes despite only being able to afford one ticket.

He progressed from local classes and dance groups to study under renowned coach Alexander Pushkin at Leningrad’s Vaganova Academy, which fed its best students straight into the Kirov. He was a comparatively late starter as a student but by the age of 20 was a leading light of the Kirov company itself. Within three years, during which he revolutionised male roles in ballet with a combination of elegant androgyny and sexually charged masculinity, he was crossing that Paris airport floor.

Almost immediately he forged an unforgettable partnership with the English dancer Margot Fonteyn, prima ballerina at London’s Royal Ballet. They were almost polar opposites, she quiet and graceful, he headstrong and brash, not to mention being 20 years the 42-year-old Fonteyn’s junior. Nureyev was determined to dance with her from the moment he settled in the west and, intrigued by the reports she’d heard from the Soviet Union and the blaze of publicity caused by his defection, Fonteyn agreed. Such was their instant chemistry, to such mutual heights did they inspire each other, that Fonteyn, who had been on the point of retiring, extended her career by a decade. Audiences loved them, queuing sometimes for days outside box offices and showering 20 curtain calls or more on their performances. It was a partnership regarded as the greatest in the history of dance.

Nureyev’s genius lay as much in his personality as his physical and musical gifts and he became almost as famous for his ego as his dancing. He could never conceive why anyone would accept standards lower than his own and could behave appallingly to company dancers. In the late 1960s he narrowly avoided prosecution in Italy after slapping a ballerina during a performance when she accidentally brushed against his arm. It didn’t matter who you were, a waiter or a world-famous cultural figure, if you fell short of Nureyev’s expectations there were consequences. During the 1980s when he revitalised the stuffy Paris Opera Ballet as artistic director, a teacher objected to Nureyev interrupting and taking over his class so Nureyev broke his jaw. Staying with Franco Zeffirelli at his home in Positano, he smashed a large and valuable collection of pottery when the film director blocked his access to a fellow house guest he desired.

This kind of behaviour predated his global fame. As a student in Leningrad he’d refused to attend a ceremony where was to be presented with a medal when he learned other dancers would be honoured too and even tweaked the nose of the KGB when they demanded to know why he had never joined the Party youth movement Komsomol, telling them he didn’t have time for such nonsense.

But his dancing was sublime. He toured widely and relentlessly, delivering consistently brilliant performances and pulling ballet almost singlehandedly into the mainstream. In 1977 he was even a guest on The Muppet Show.

Nobody can go on forever, however, and when Nureyev was diagnosed HIV positive in 1984 it wasn’t long before his condition exacerbated the ravages of age and the years of pushing his body beyond its limits. When he toured Britain in 1991 reviews were mixed at best. Billed as Nureyev’s farewell tour, at which the dancer sniffed “it is not my farewell tour, impresarios called it that to sell tickets”, the Guardian wrote of a performance at Wembley Conference Centre in which, “Rudolf Nureyev looks his age and grimaces a lot… the sadness of this so-called Farewell Tour is that Nureyev’s dancing is now so pitiful.”

He was 50 years old but in the minds of the audience he’d transcended age to become practically immortal: to them he would always remain in his leaping 20s. It’s the performances in his prime for which he’ll be remembered, with and without Fonteyn, leaping, flying, spinning, taking ballet to unprecedented heights by channelling sheer determination and faultless artistic integrity into every muscle and every sinew.

“Every time you dance it must be sprayed with your blood,” he said in 1971. “So much effort for so little reward. Not from the public or critics or the box office. For yourself.”