The great European astronomer Caroline Herschel discovered more than eight comets. CHARLIE CONNELLY adds to her star-borne legacy

“At the heavens there is no getting, for the high roofs of the opposite houses.” It was Boxing Day, 1822, when Caroline Herschel wrote these words in a letter to her nephew. She was 72 years old and had recently returned to her home town of Hannover after spending 50 years in England becoming one of the most important women in the history of astronomy. The discoverer of eight comets and a visionary cataloguer of the heavens, she had spent countless nights squinting through her one good eye into a telescope, sweeping the night’s canopy for uncharted stars or the tell-tale twinkle of a new comet arcing through distant skies.

The death four months earlier of her brother William, founding president of the Royal Astronomical Society and since 1782 the King’s Astronomer, with whom she had worked tirelessly for half a century, affected her deeply. It was grief that prompted the ill-judged decision to abandon England and return to the town where she had spent her formative years. Being away from the telescopes she had helped William to build was one thing, being crowded out of the night sky altogether by the tall Hannoverian buildings only increased her sense of ennui. She could barely see the moon.

Today there is a crater in the bed of the moon’s Sea of Showers named for Caroline Herschel and the comet 35P/Herschel-Rigollet that passes within sight of the Earth every 155 years is also a tribute to her work. Back on Earth, in 1838 she became the first woman to receive the gold medal awarded by the Royal Astronomical Society – it would be 158 years before another woman received the award – and in 1846, her 96th year, she received a Gold Medal for Science from the King of Prussia, recognising her “valuable services to astronomy” rendered by “discoveries, observations, and laborious calculations”.

Such honours still lay ahead of her as she cricked her neck at the window trying to see the stars that first Christmas without her brother in a land at once familiar yet strange: Hannover had changed almost beyond recognition in 50 years. Without her beloved brother, blocked from the stars and having already lived to a grand age, she must have felt as if her time was almost up but, as ever, Caroline Herschel wasn’t done yet. She would live for another 26 years, still making a valuable scientific contribution through cataloguing and interpreting data even if she couldn’t scan the heavens herself.

Such longevity was unthinkable when at the age of 10 she contracted typhus. Ill for months, sometimes dangerously so, the fact she only grew to be 4ft 3in was attributed to a disease that also deprived her of the sight in her left eye. For her mother Anna this meant only one thing: this daughter, her eighth child, would never marry and from an early age Caroline was prepared for life as a housemaid. Educating her would be a waste of time and money.

Her father Isaac disagreed. An oboist and conductor in the military, he recognised Caroline’s intelligence and sought to encourage it. Long absences from a home where his wife ruled the roost frustrated attempts to give his daughter options, however. And, despite his teaching her whenever he had the chance, by the time she embarked on her twenties Caroline’s only significant education was as a seamstress. When Isaac died in 1772 it appeared her course was set but William, 12 years her senior and a music teacher in Bath, had other ideas. He sensed his sister’s melancholy from her letters and returned to Hannover determined she would accompany him to England where he would train her as a singer. It took several weeks to persuade Anna but on August 16, 1772, Caroline crossed the English Channel to a new life, aiming to “make the trial if by his instruction I might not become a useful singer for his winter concerts and oratorios”.

William sought to coax the potential he’d recognised from a woman conditioned to believe she was practically worthless. Noting a nascent talent he coached her tirelessly and before long Caroline was a well-regarded soprano performing with him in the concert halls and salons of Bath and Bristol, taking leading roles in major works like Handel’s Messiah.

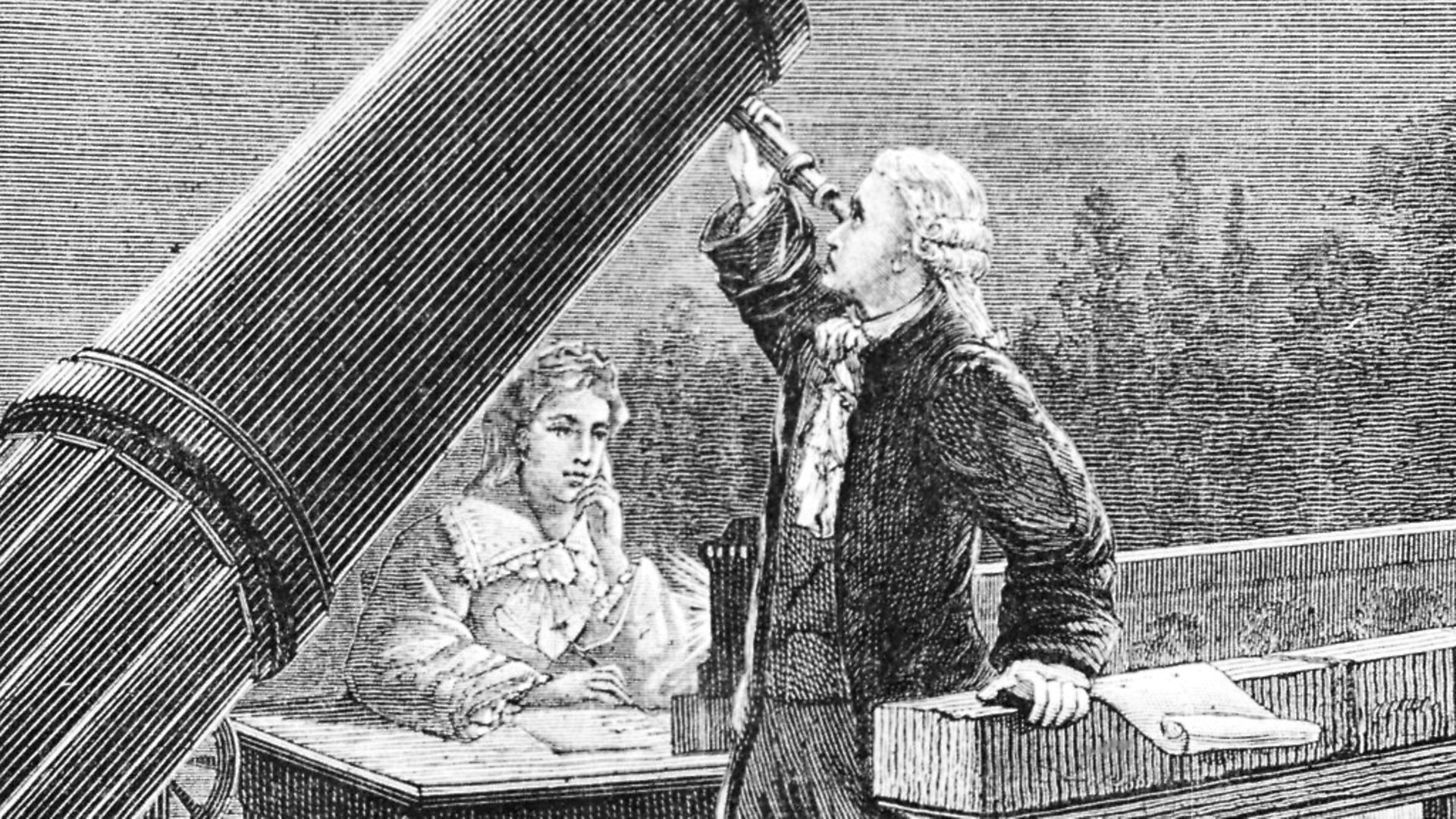

Performing in public could not shift entirely the conditioning that had battered her self-esteem, however, and whenever other impresarios or conductors would approach her with offers of roles she would refuse them all. The thought of singing under anyone but her brother terrified her. Thus when William eventually abandoned music for his new passion of astronomy in the late 1770s it spelt the end of Caroline’s singing career. He’d been spending spare evenings engrossed in books about the stars, repeating what he’d learned the previous night to his sister over breakfast. She absorbed everything. Before long he was enlisting Caroline’s help in grinding and polishing lenses for the telescopes he was building and made Caroline his assistant, calling out his observations to her from his seat at the telescope to record in the copious notebooks she would fill for the rest of her life. Caroline was no mere stenographer, however. The data she was recording required advanced mathematical skills to interpret, something that came to her quite naturally.

By the turn of the 1780s, thanks in no small part to Caroline’s labours with grinder and pen, William was able to abandon music altogether, discover the planet Uranus and be appointed to the post of King’s Astronomer. Prestigious though the role was it had its drawbacks. Not only was it a reduced salary from his musical activities, the job necessitated a move closer to George III’s royal residence at Windsor as the King’s Astronomer was required to be available at the whim of the monarch. The Herschels moved first to Datchet and then to the observatory at Slough, and while Caroline was never a mainstay of Bath society the contrast between the lively, cultured city and the provincial backwater that became her home was marked.

She combatted loneliness and isolation by working tirelessly, sometimes at great physical cost. On New Year’s Eve 1782 she was badly injured during a nocturnal observation, impaling her leg on an iron hook as William called for her to adjust the angle of his 40-foot telescope.

“[William] and the workmen were instantly with me but they could not lift me without leaving nearly two ounces of my flesh behind,” she wrote later. “A workman’s wife was called but was afraid to do anything and I was obliged to be my own surgeon by applying aquabusade and tying a kerchief about it for some days till Dr Lind, hearing of my accident, brought me ointment and lint, and told me how to use them.”

The doctor told William later that “if a soldier had met with such a hurt he would have been entitled to six weeks’ nursing in a hospital”. Caroline Herschel was back recording observations within a couple of days. When William married a local widow in 1783 it could have exacerbated the dislocation Caroline felt in Berkshire. Instead she grasped her new intellectual freedom and gradually felt confident enough to begin making her own observations. “It was not till the last two months of the same year before I felt the least encouragement for spending the starlit nights on a grass-plot covered by dew or hoar frost without a human being near enough to be within call,” she wrote of work she would come to describe as ‘minding the stars’.

Within three years she had become the first woman to discover a comet and in 1796 became the first woman scientist to receive a salary when George III awarded her an annual stipend of £50. That year she commenced work on her other great achievement: reworking and updating John Flamsteed’s 1725 British Catalogue of the stars he had observed from the Royal Observatory at Greenwich. It took nearly two years but Caroline Herschel’s Catalogue of Stars not only corrected many errors but introduced 560 new heavenly bodies in a work that remains a valuable resource today.

Even when she returned to Hannover she kept up her cataloguing work, reorganising, correcting and indexing notebooks for her nephew and fellow astronomer John Herschel. Despite her clear gifts and achievements, the early intellectual and social stifling by her mother left Caroline’s self-confidence in tatters for the rest of her life. When invited to the Royal Observatory at Greenwich by the Astronomer Royal Nevil Maskelyne during the 1790s she told him, “I am nothing. I have done nothing”. She did add, however, that the invitation had “flattered my vanity”, before adding revealingly that “among gentlemen this commodity is generally styled ‘ambition'”.